A tireless scholar of the intersection of black identity and labor, visual artist Lubaina Himid creates work that has a lot to teach us about separating the self from production in the current moment

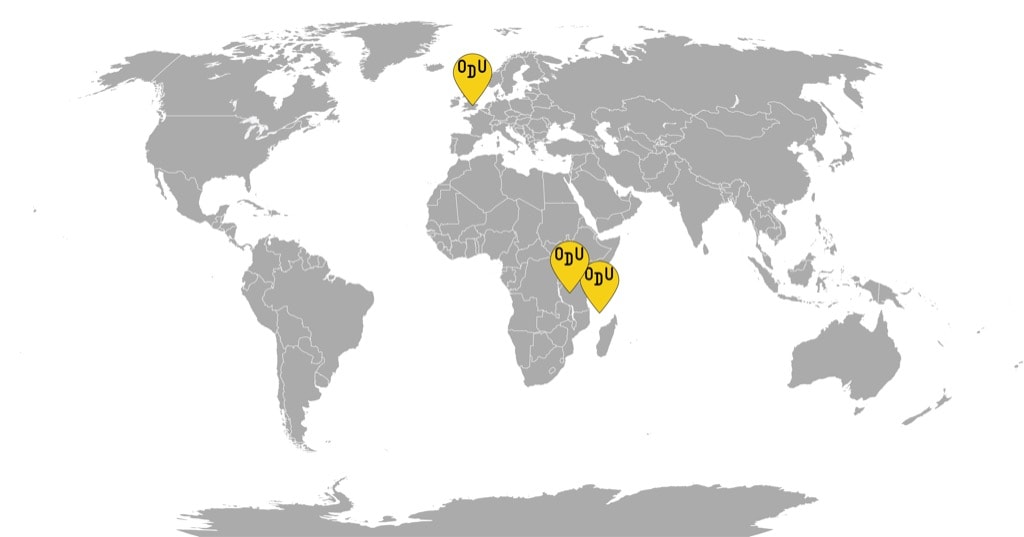

FROM UNITED KINGDOM, COMOROS and TANZANIA

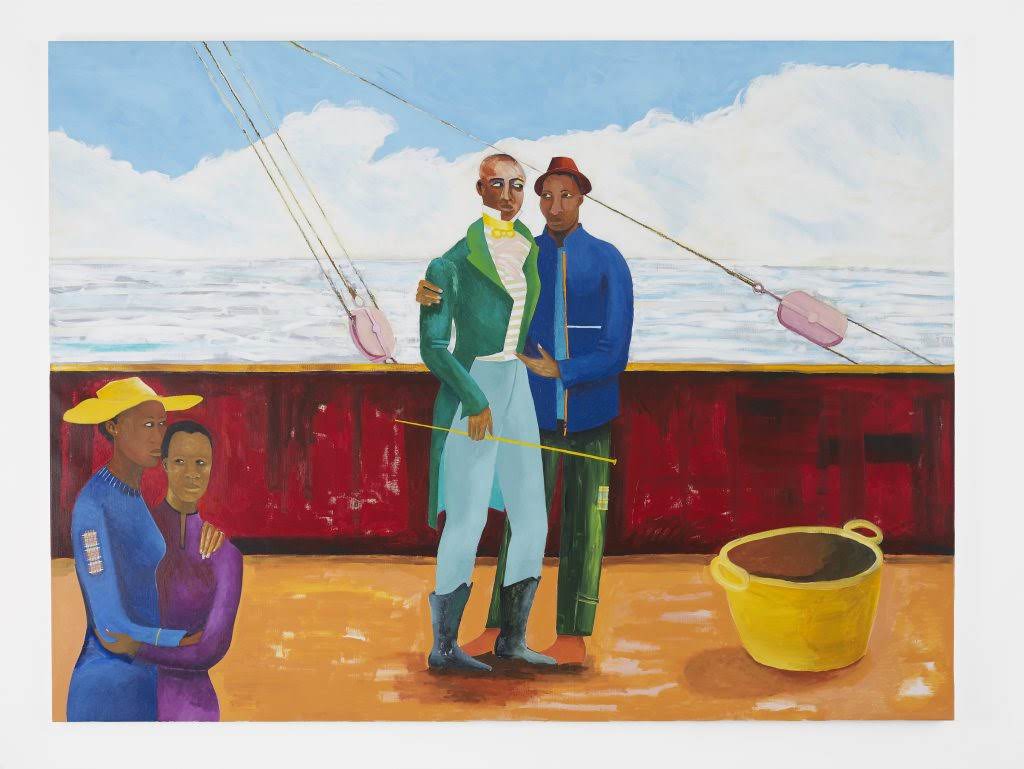

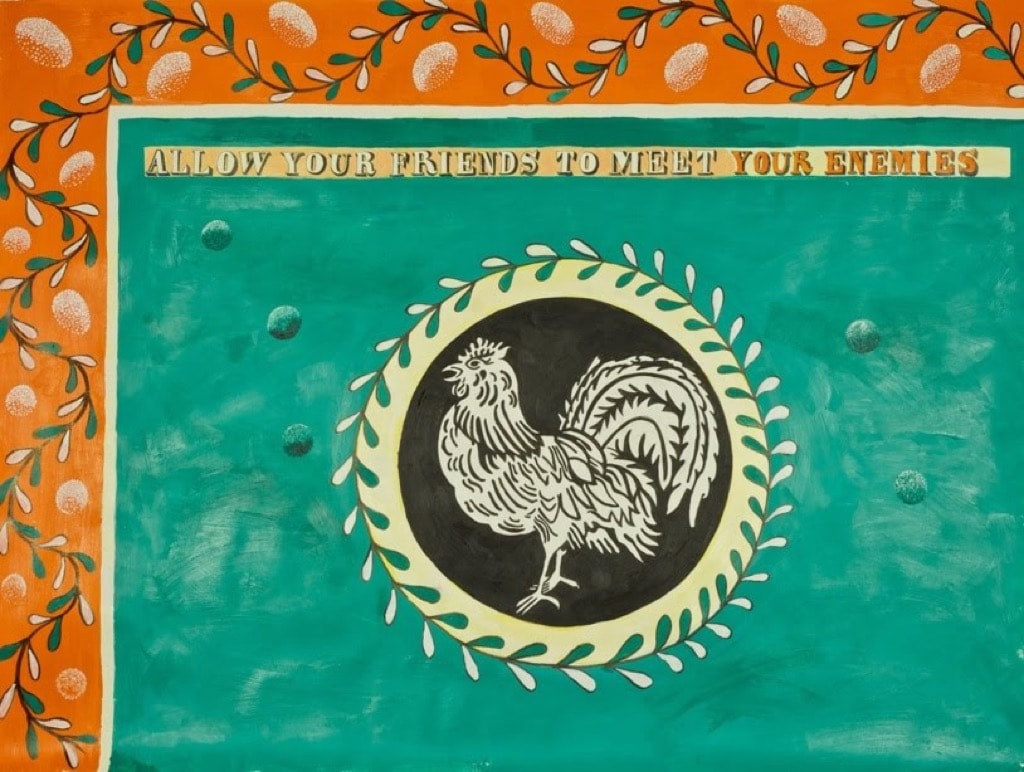

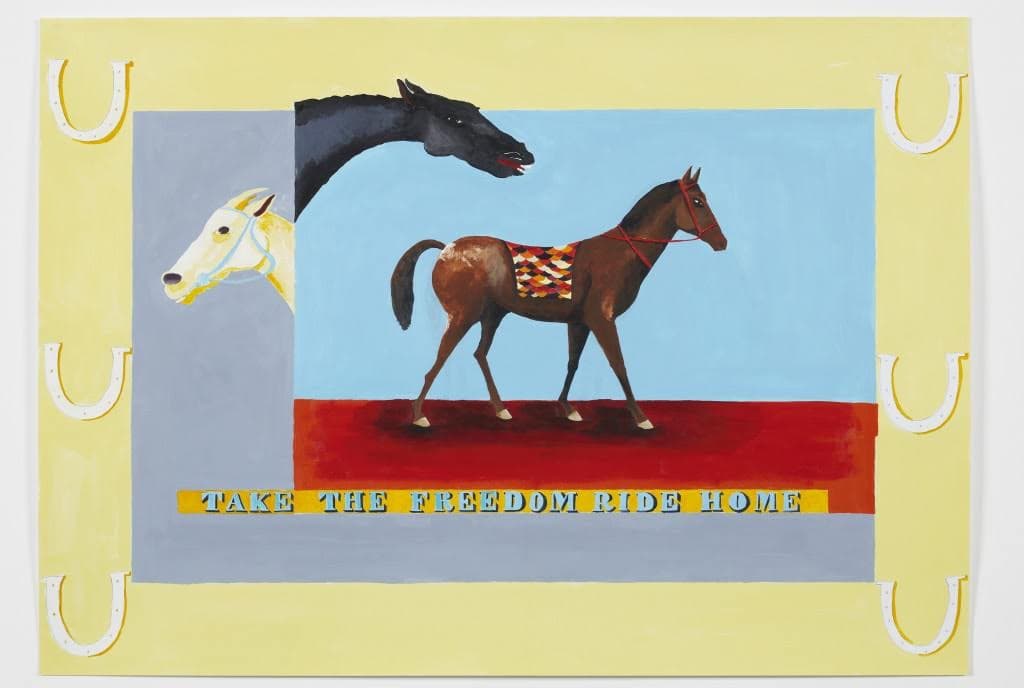

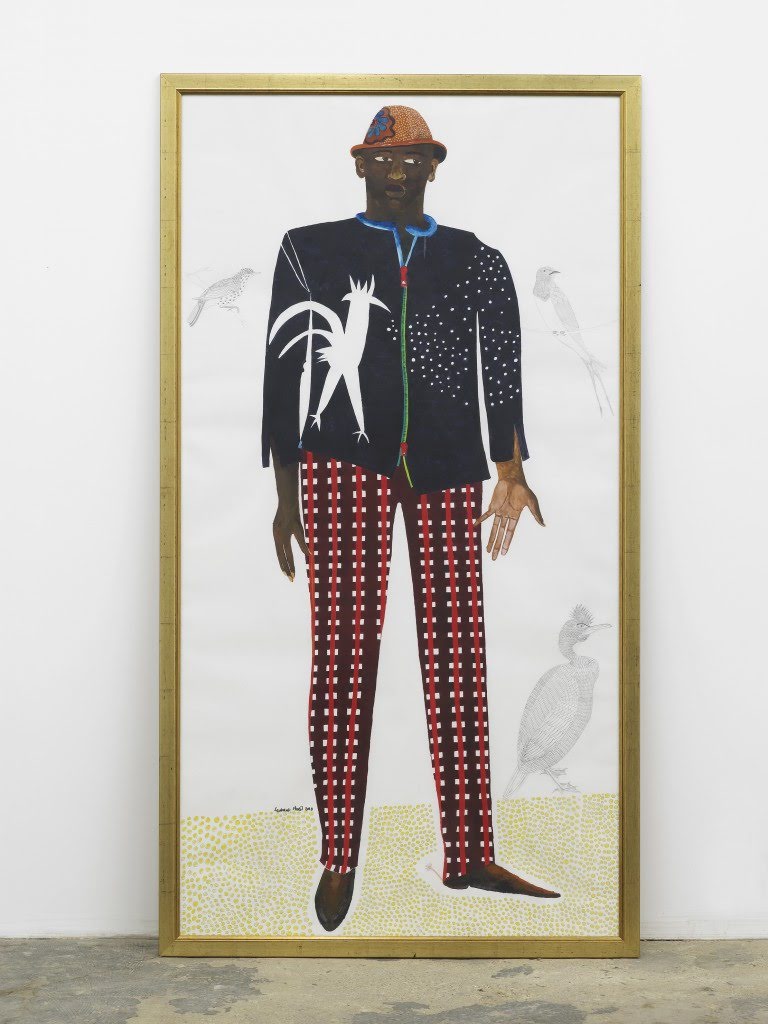

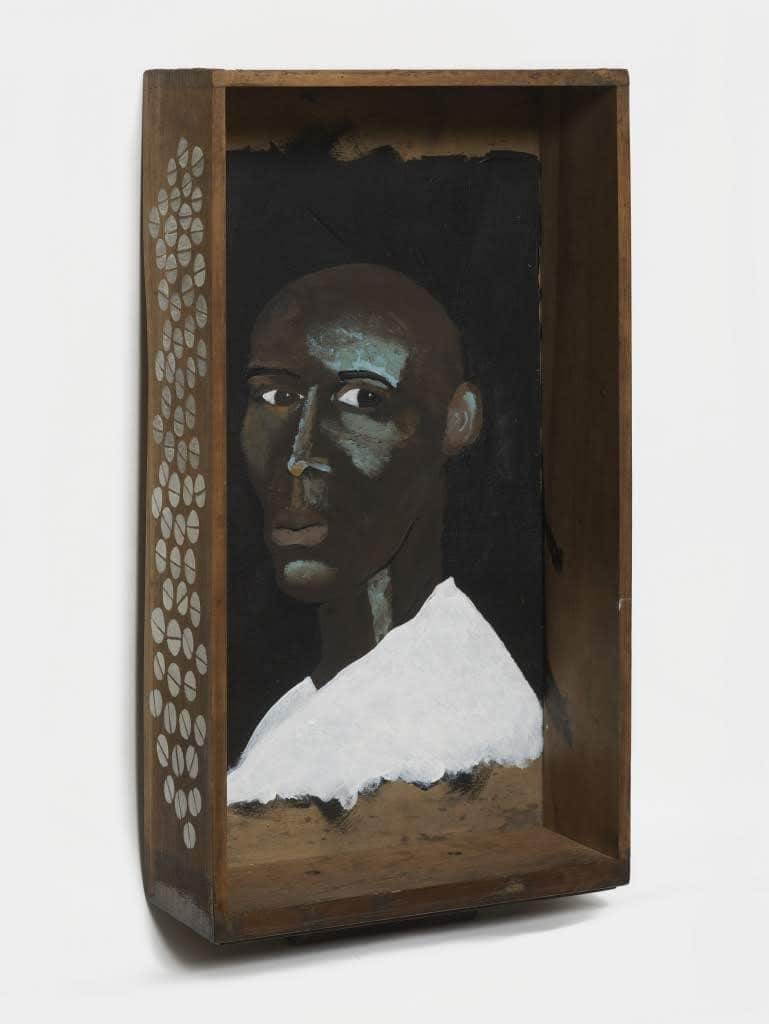

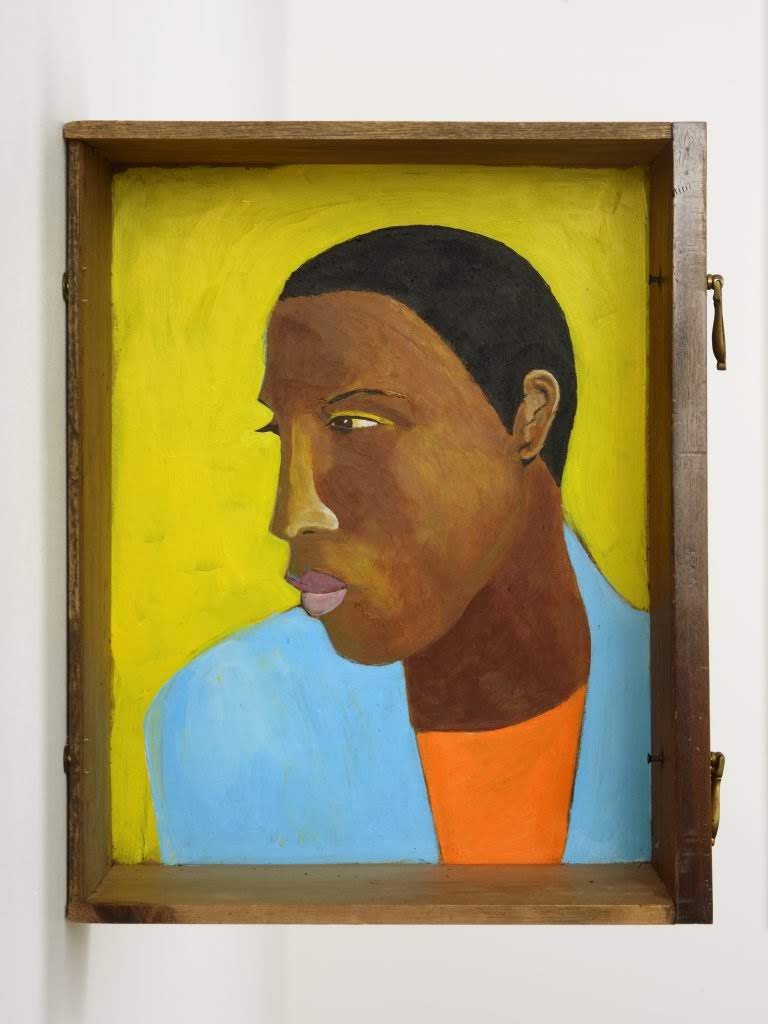

WHAT’S GOING ON: Elaborate portrayals of dark-skinned individuals are interspersed into the lavish background of the Victoria & Albert Museum. But figures are separated from their masters, to give back agency to the enslaved, whose blood and labor made wealth accumulation possible and became the basis for contemporary capitalism. Bright, full-size wooden cutouts show human figures from William Hogarth’s satirical paintings that mocked the mores of the 19th century’s bourgeoisie reimagined for the realities of the late 20th century. In them, Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Raegan are portrayed as debauched lovers, a missile shooting out Raegan’s crotch, as the parallel is being drawn between the politics and the art world, where capitalist complicity is key. Kanga, the colorful rectangles of fabric that East African women use as pieces of clothing or home accessories, from skirt to head-wrap, from pot-holder to baby carrier, are repurposed, through infusion with colors and meanings that communicate belonging in the world ravaged by industrialization. Their material, cotton, the ubiquitous fabric both in garment production and labor exploitation, adding an extra dimension. Meanwhile, meticulously painted and cowry shell-decorated wood planks that compose a disintegrated or not yet assembled ship, create a skeleton of an ominous presence that shows how the commodification of the flesh is never too far away. Thoughtful, visionary, and revisionary, brave, and populous, Lubaina Himid’s works span a whole career of establishing black visibility and eminence.

WHO MADE IT: Born in Tanzania, then the Kingdom of Zanzibar, to a Comorian father and a British mother, Lubaina Himid has been living in the UK most of her life. A professor of Contemporary Art at the University of Central Lancashire, Preston, she is not merely an artist who exercises her passion. Himid had been pursuing the task of creating space for black identity in British art since she began her career in the 1980s. And not only did she become one of the pioneering figures of the British black arts movement, but also the first black woman to receive the Turner Prize, as well as the oldest recipient of the prize ever, at 63—the achievement long overdue and riddled with disregard for other women of color by the British cultural establishment. Himid refers to herself as a “political strategist” because her creative pursuit was always following a precise trajectory, where the visual language is the tool with which she pursues the agenda of starting a conversation and creating change—an admirable guiding principle by which for all creatives to live. She is represented by Hollybush Gardens in the UK, and Himid’s works have been exhibited in the UK’s defining museums, who have also purchased pieces for their collections. In 2019, she had her first solo exhibition in the US at New York’s New Museum, where the great American poet Fred Moten provided texts for the catalog.

WHY DO WE CARE: The art landscape today is more and more abundant with astounding voices of artists of African-American, Black British and African descent, and it makes it twice as important to remember whose shoulders they are standing on. Even though she was not the sole black artist battling with the status quo to garner significance in the British art world, Himid is remarkable because of the exhaustive approach that she used to make her case. It’s as though this woman has taken upon herself the task of reimagining art history as if the black personhood had a place in it throughout the years of slavery, meticulously recreating the objects of commemoration and relevance, and not merely mimicking the aesthetic but injecting seamlessly into it. And even though no gallery or museum will offer you this luxury, it’s best to explore her works in their vastness and entirety. This way, one can partake of the natural evolution of her subjects because Himid’s outlook is never constricted or fossilized. Just like the impact of black bodies on the art space, it continually evolves and shifts, taking on newer meanings and connotations, as well as emerging more clearly.

WHY YOU NEED TO PAY ATTENTION: While a fully valid enjoyment of Lubaina Himid’s work is entirely possible through the purely aesthetic appreciation of their exaltation on the border of identity, belonging, and self-awareness, one of the most exciting particularities of her work is the way she approaches labor. She began by making sure that the slave ancestors get the recognition they deserve for the blood and toil, which underlines the economy. Then, she proceeded to liberate them of this work, allowing them to reemerge as survivors of the new reality, where the economies of preceding times are mere ghosts. Today, as we see capitalism crumble while its lifeblood, the hot red of the workers’ veins is restricted in flow, the very same modality of Himid’s works is reiterated in real life. And from this space, we can rebuild anew, using the creative cache of inquisitive, methodical artists, much like Himid herself, to inform a new theory of resource management and communality. Significant in the way it layers realities and invites them into a conversation, Himid’s work is never restricted by choice of medium, and makes the transition from paper to wood on a whim. And because Himid infuses her artworks with powerful messages that transcend the border between fine art and folk art, what’s created is a body of work as accessible and useful as it is ontologically meaningful. A visual history of the people that became inextricable from the larger picture of British and World culture, Himid’s work is a testament to the only kind of labor that has the right to define an individual: the intellectual labor, of which Himid is a resilient, vivid master.

For more content like this sign up for our weekly newsletter

MORE LUBAINA HIMID