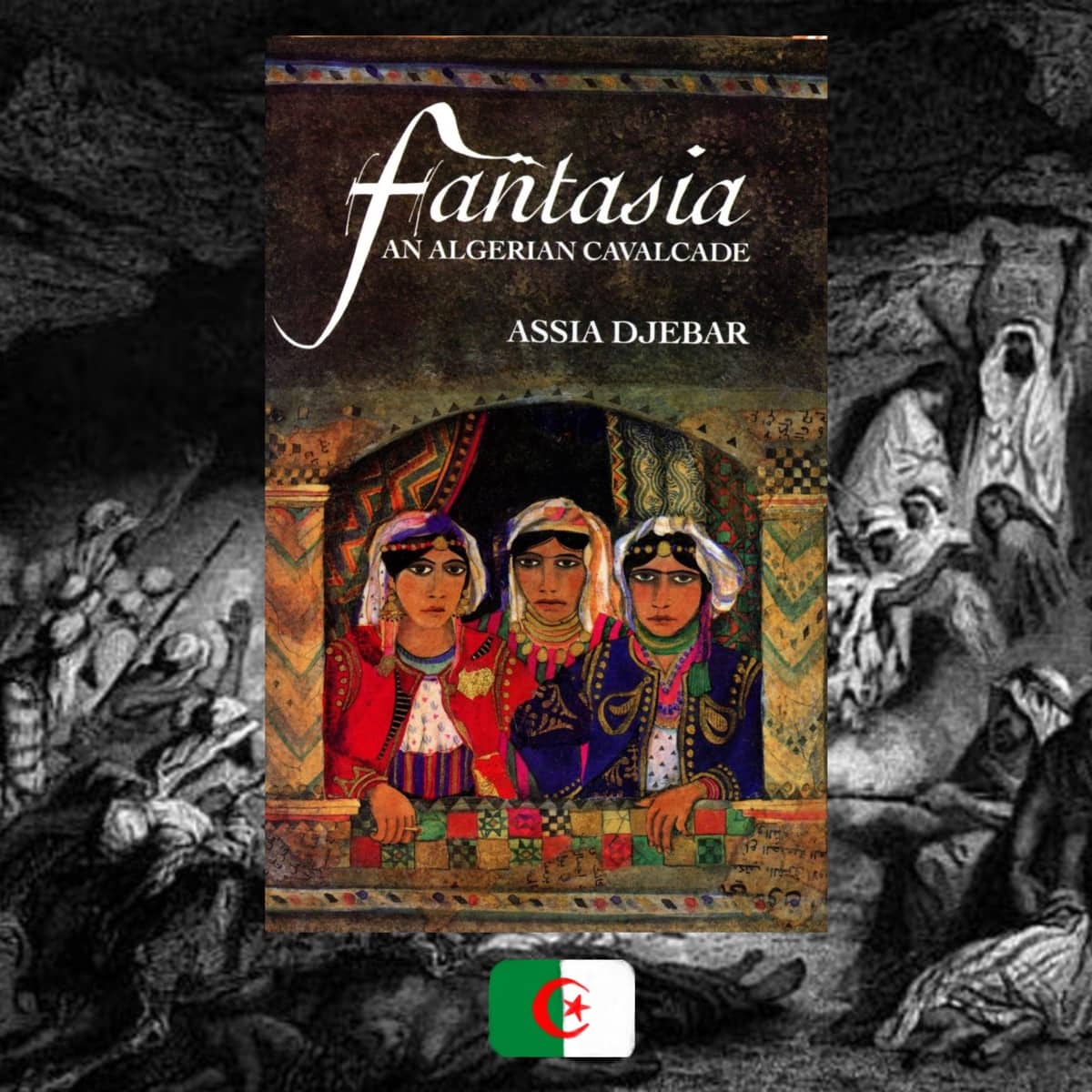

A linguistically ornate exercise exploring postcolonial history and identity, Assia Djebar’s account of her homeland is a monument to the country’s women and their heroic lives

FROM ALGERIA

WHAT IT’S ABOUT: Many voices come together to tell the history of Algeria through a fragmented narration. Some of them belong to the men, foreigners, colonizers, soldiers, and journalists who came to the distant land to plunder, conquer, or marvel at the oddities. But the most prominent voices belong to the Algerian women. The narrator relays fragments from the author’s own biography and links them to the significant historical events in Algerians’ strife against subjugation and for independence. Meanwhile, a chorus of voices, disembodied but resonant, present oral accounts of women who took part in the liberation during the Algerian War: mothers, wives, widows, sisters, lovers, fighters, prisoners, martyrs. Finding her own voice, which she initially lost in switching to the French, Assia Djebar also gives voice to those whose accounts had been buried by the more prominent men and the foreigners in possession of the lingua franca.

WHO MADE IT: Assia Djebar was born as Fatima-Zohra Imalayen in Cherchell in then-French Algeria, in a family of Berber origin. The daughter of a French teacher, she was reared at the intersection of the languages, one enforced, another forbidden; the native and the colonizing cultures; and generational history and the yoke of the French rule. Always different from those surrounding her—the first Muslim in her prestigious school in Algiers, and the first Muslim and Algerian at the école normale supériere in Sèvres, and France’s elite educational system in general—she became an astute observer of reality. Her first novel came out when Imalayen, already under the penname of Assia Djebar, was just 21: known as “The Mischief” in its English translation, it centered around a young, affluent French-Algerian woman coming into her own. And even though the later writing spread across the class lines to feature many different voices, Djebar’s allegiance remained with the language, femininity, and the wounds of history. Living between her two countries, she wrote many books about women in the Algerian, general Arabic, and French contexts, and produced plays and films on the same subjects: one of them even snatched a FIPRESCI prize at Venice Film Festival. Djebar went on to join the Académie Française (first North African to do so and the fifth woman), received the prestigious Neustadt International Prize for Literature in 1996, taught history at the University of Algiers, and chaired the department of French literature at NYU. She died in 2015.

Dorothy S. Blair was a translator and one of the preeminent experts on the francophone literature from Africa of the second half of the 20th century. She was the head of the Department of Romance Languages at the University of Witwatersrand. She translated a diverse array of francophone authors even after retiring, including French-Lebanese Amin Maalouf, Senegalese Mariama Bâ, Aminata Sow Fall, Birago Diop, and Nafissatou Niang Diallo, Algerian Leïla Sebbar and Aicha Lemsine, and others. Blair died in 1998.

WHY DO WE CARE: As reflected in literature, Algeria is mostly known for the way men wrote about it. Of course, the first association is always “The Stranger”; however, we had previously offered to reinvestigate the same landscape through the eyes of the brother of the man killed by Camus’ Mersault. And, of course, there is always Yasmina Khadra, the definitive Algerian writer hiding behind a woman’s pen name. Djebar’s main project, both in writing “Fantasia,” and in her other works, was to change this view of the world where she was raised and where her compatriots fought and died. Because, as Blair notes in her brilliant preface to the novel: “The hero of the Algerian resistance to the French conquests was the legendary Sultan Abd al-Qadir, but the episodes which stand out here are those featuring the sufferings of women: victims of the ruthless ’fumigations’ of rebel tribes in the Dahra caves, dancing girls caught up in the fighting, anonymous women whose hands and feet are amputated for their jeweled ornaments…”

In “Fantasia,” the issues of language and expression keep being mentioned, for instance, the love letters that Djebar’s childhood friends send to faraway penpals, or the voices that narrate the Independence War in a chorus of grief and memory. Each of these applications of language offers ways for a story to be told from the point of view previously unexplored. But it’s not just that the women had been deprived of a way to express themselves historically, in Algeria as much as everywhere else. Language is also a barrier, which made the experiences of the colonizing Frenchmen, whether involved with the army or just random eyewitnesses, the defining narrative for a long time. Djebar shows this by digging deep into the archives of writing about Algeria by those who visited it during the wars and counterpointing their descriptions with the knowledge of the events she possesses as a historian. “Their words, lodged in volumes now gathering dust on library shelves, present the warp and woof of a ‘monstrous’ reality, that is made manifest in all its unambiguous detail. This alien world, which they penetrated as they would a woman, this world sent up a cry that did not cease for two score years or more after the capture of the Impregnable City… And these modern officers, these noble horsemen, riding with their powerful arms at the head of their motley corps of infantry, these new crusaders of the colonial era, overwhelmed by such a clamour of voices, wallow in the depths of concentrated sound. Penetrated and deflowered, Africa is taken, in spite of the protesting cries that she cannot stifle”.

Finally, it is through her mastery of the French language—which she called “father tongue” because of her father’s influence, and because it was enforced on the Algerians at the time, driving Arabic and other tongues into the shadows,—that her writing is allowed to bear witness. Not just within the country but outside, finally having a chance to counter the fossilized memories of French men with the living, breathing, and seething anger of the Algerian women.

WHY YOU NEED TO READ: “Fantasia” offers an incomparable insight into the many events of the Algerian colonization, struggle under the French rule, and ensuing independence, which are not often mentioned, buried under the mass of what we know more readily. Here they are assessed from the point of view of the women. The most harrowing are the stories of the fumigations in the caves when general Cavaignac asphyxiated the whole Sbeah tribe, and then his colleague Pélissier did the same with the Ouled Riah tribe. But we also see the smaller tragedies that leave crevices just as deep. A sister loses her rebel brother to the French interrogation. A young woman feels her eyes swell up with tears whenever she sees the French tricolor—because it reminds her of the blood of her comrades guillotined in Lyons. It’s always the women’s resistance, the circles of women, that stand at the beginnings, that meet the conquest, trying to ward off the evil intruding eye. And it’s always the women still standing after everything else has fallen apart. According to a relative in Djebar’s recollections, the first person to be Muslim was a woman. It’s only logical that the first instance from which to receive the message of being female in Islam should be a woman, too. “How shall I find the strength to tear off my veil, unless I have to use it to bandage the running sore nearby from which words exude?” Djebar asks as trauma, repression, and confusion take shape through verbalization and vocalization.

Even when you receive it in the form of Blair’s translation—powerful, energetic, and faithful—you remain privy to the games that Djebar plays with the French tongue, twisting it, abusing it, inflicting harm. And she knows exactly what she is doing, as her personal history is inseparable from the language’s influence on the nation, from when she was just learning the language, with its foreign species of animals and unfamiliar concepts, like parents walking alongside each other, to when she could finally use it to describe the many experiences suffered by the Algerian women, who were being silenced in their own languages and this foreign, violating one.

“This language was formerly used to entomb my people; when I write it today, I feel like the messenger of old, who bore a sealed missive which might sentence him to death or to the dungeon.”

By laying myself bare in this language, I start a fire which may consume me. For attempting an autobiography in the former enemy’s language…

A language imposed by rape as much as by love…”

Djebar’s prose is not instantly accessible: just like the trance-like ritual that her maternal grandmother engaged in, a frenzy of song and movement all around, it is a hypnotic, overpowering experience, which absorbs fully and takes a while to emerge from. Going through the book, with its wars and ravages, is an experience that taxes the mind and the soul, that takes but does not give back, that drains of faith. And yet, somehow, it reassures, because if the words had been written, if a language had managed to preserve something, it means that Algeria lives on. Djebar’s voice will not be the last to sound Algeria thunderously, but it was the first that invited other female voices to join in. And this novel, full of blood, grief, and yet, ululation, is a linguistic monument to all the women, audible and voiceless, that will allow them to remain in posterity.

Fantasia: An Algerian Cavalcade (L’Amour, La Fantasia) by Assia Djebar

Translated by Dorothy S. Blair

For more content like this sign up for our weekly newsletter