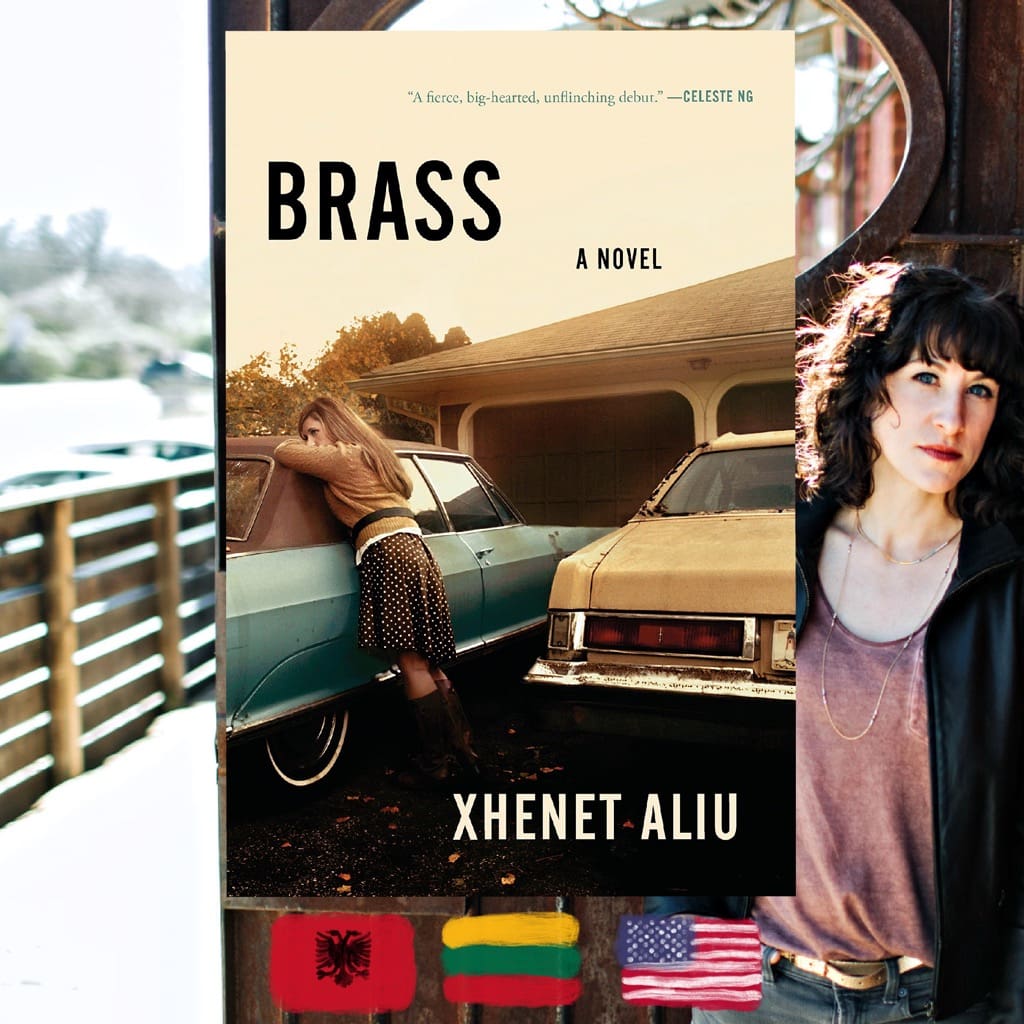

Whether he’s depicting socialist worker heroines, women alienated by their fragility, or experiments with the Byzantine heritage, Hasan Nallbani is Albania’s foremost master of the female portrait

FROM ALBANIA

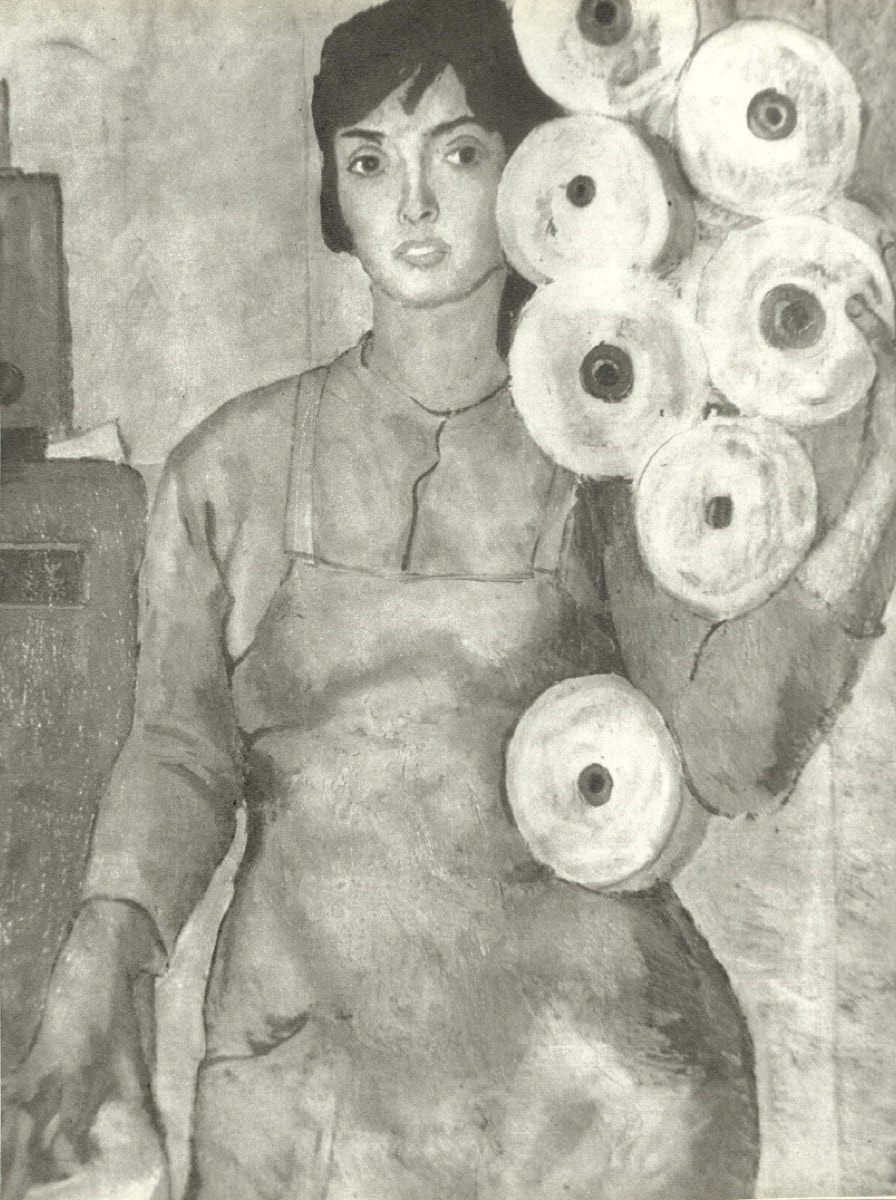

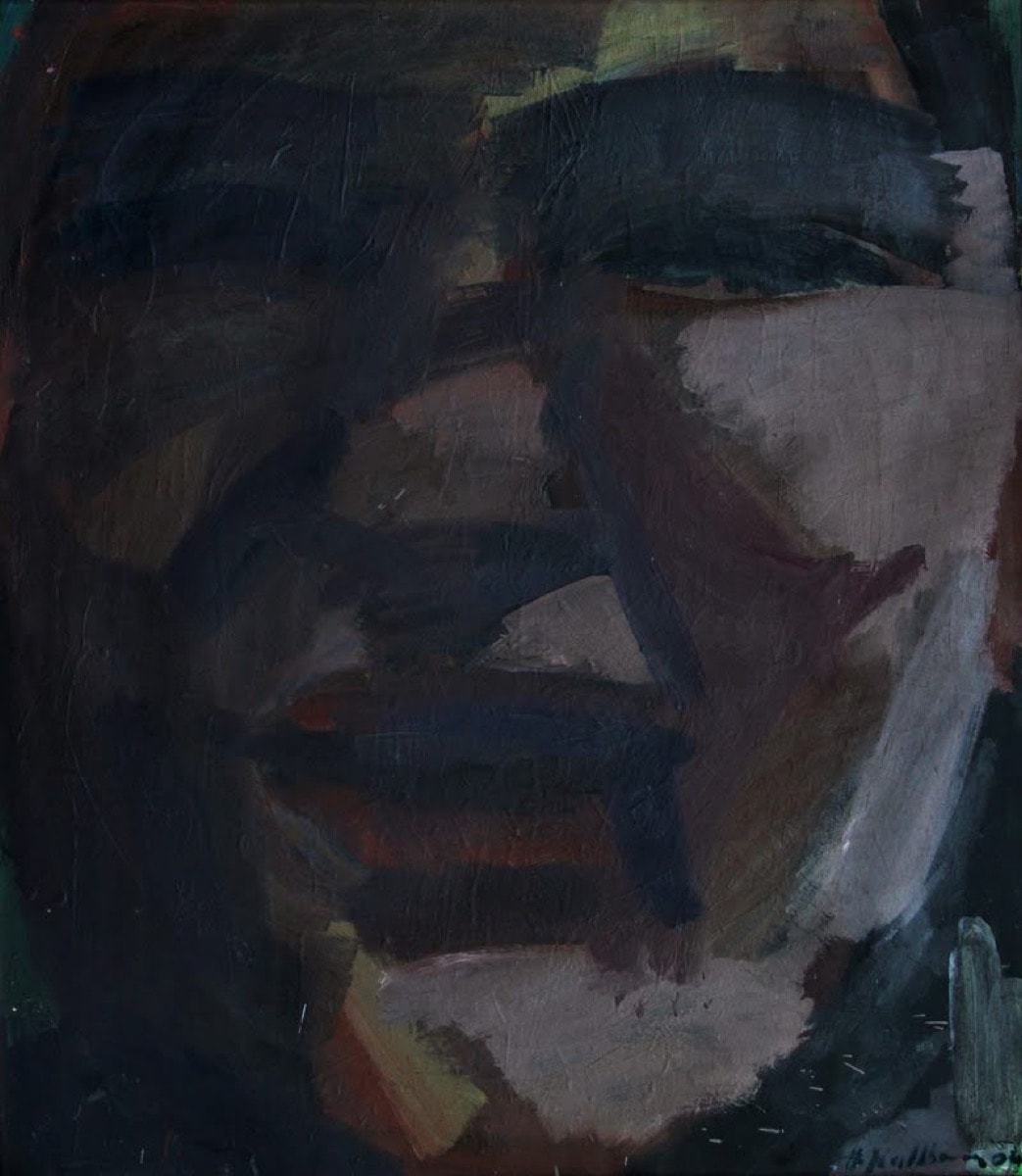

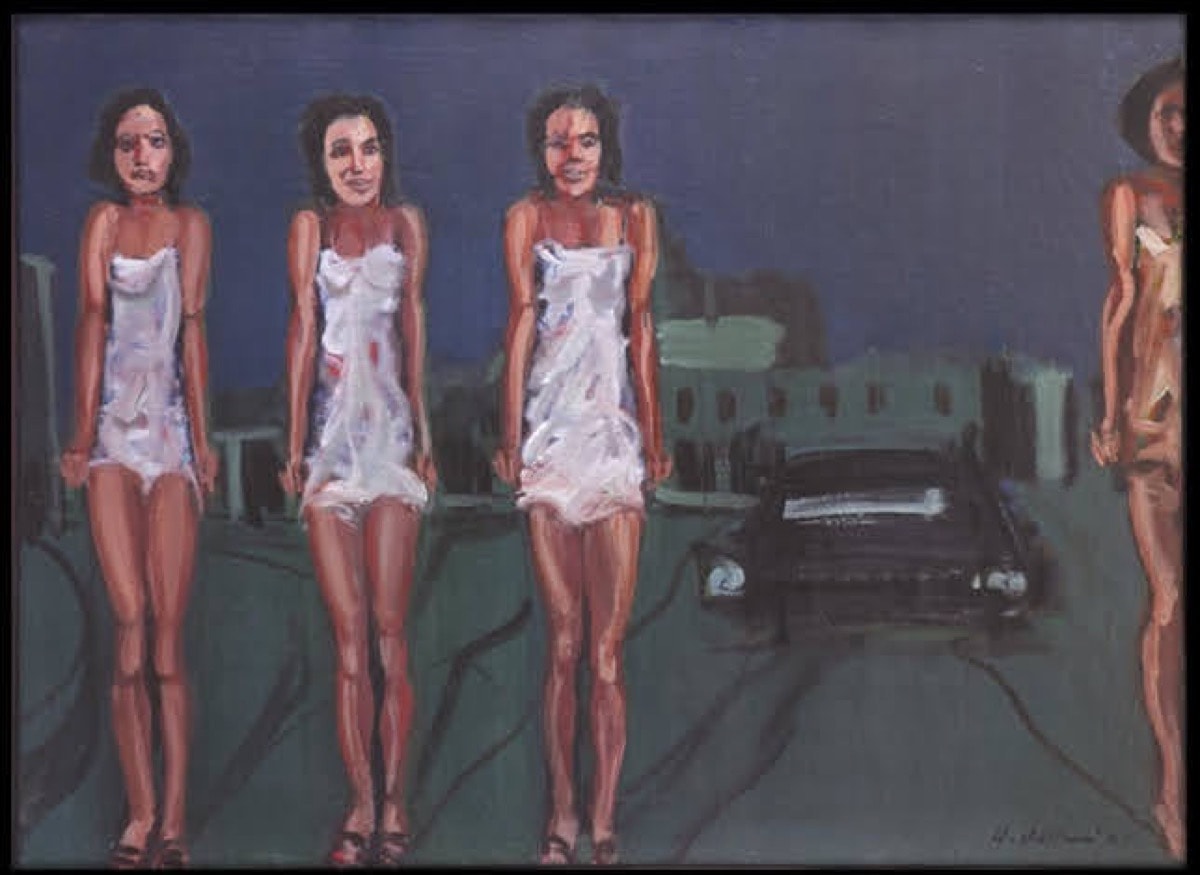

WHAT’S GOING ON: WHAT’S GOING ON: The earlier works, rendered in a hearty social realism, feature proud women, who fill in the entire frame with their impeccable poise. They break the fourth wall by glancing right at the viewer, a quiet, resolute gratification from knowing their vacation in life on their faces, as well as gentle annoyance with the artist tearing them away from it. The colors are bright, clear, and the lines are precise, vague enough to stay faithful to the human silhouette, but defining it in specific terms. As the artist’s path progresses, the style becomes more abstract, and the colors darken. His subjects are still women, but now they are crowded, lined up as usual suspects, or even crowded so tightly they become a blur, where only faces, all different but made up to a striking resemblance, come to the forefront. The clothes become scanter, sometimes leaving the ethereal female form naked, exposed to the elements and vulnerable amidst the alienation that the artist so aptly depicts, and at times even taking on a martyred air. These are the works of Hasan Nallbani, the Albanian artist who began his career during the country’s socialist era, and then continued painting throughout the many transformations, his eye firmly centered on the country’s women.

WHO MADE IT: Born in 1934 in the picturesque city of Berat, Hasan Nallbani got his start working as a scenographer at the People’s Theatre in Tirana. Then he had the luck to study under painters Nexhmedin Zajmi and Guri Madhi, both classical stalwarts of the Albanian art scene. Nallbani first gained prominence as an artist when he depicted the workers on the front line of Enver Hoxha’s socialist government’s efforts to organize labor to work on Albania’s urban and rural infrastructure. His portraits of workers, of which two women’s depictions can be easily tracked down now, have been vastly discounted in the post-socialist landscape when social realism fell out of fashion. Hopefully, they’ll make a sweeping return now. After the fall of socialism, Nallbani continued his art practice, which changed with the times, and also went into restoration. He is currently one of the foremost experts on Byzantine art in Albania’s Orthodox Christian churches and a big champion of the now largely forgotten legendary icon painter Onufri. Nallbani led the project to create an iconography museum dedicated to Onufri’s legacy in St. Mary’s Cathedral at the historical castle in his hometown of Berat. The influence of Onufri’s frescoes and the Byzantine style is also noticeable in his own works. Throughout the years and governments, his work has brought Nallbani a range of awards; however, he has expressed disappointment with the contemporary Albanian art scene.

WHY DO WE CARE: Albania’s culture has been most known worldwide in the past years due to the sudden emergence of various young female pop-stars of Albanian origin: Rita Ora, Dua Lipa, Bebe Rexha and others. Lipa recently sparked controversy and much online discussion on right-wing soft-power by posting in support of Albanian nationalism. The issues of the country’s right lean and the poverty caused by rampant, gangster-style neoliberalism of the post-communist era are typical for the former members of the Non-Aligned movement as well as the ex-Soviet countries. And just like in other territories, this incline comes with a fierce rejection of the country’s communist past, including the time when Enver Hoxha was in power: an interesting wrinkle since Hoxha’s own ideology was staunchly anti-revisionist.

Of course, all of these political concerns also influence the art field, where the crevice between the socialist realism of the past and the contemporary styles that developed through the influence of Western modernism remains wide. Other artists who began around the same time as Nallbani have been more outspoken on the transitions and how their practice had been affected. But Nallbani is a quieter, more subdued presence, whose works, meanwhile, are ripe for interpretation for a keen observer. Whether working in social realism or branching out to abstraction, his main interest remained in the female heroine and how he saw womanhood during socialism and after hints at peculiar transformations in the psyche and self-possession of the nation.

WHY YOU NEED TO PAY ATTENTION: Because today Albania has the pouty-lipped face of its pop starlets attached to its international image, it’s crucial to understand the role that womanhood plays in the country’s context. And what better visual aides can be found than Nallbani’s portraits of women through the ages? The self-assured youth activists from the 60s are a vigorous portrait of the many feminist reforms undertaken to divert the country from one of the most patriarchal societies in Europe at the start of Hoxha’s rule. Nallbani’s later paintings show women seemingly liberated but co-opted into the economic shifts happening in the country, under which their voluptuous figures shrivel, and difference dissipates under a renewed license on homogeneity. They’re the simulacra of the once again status-oriented society, where the commodification of a women’s liberation is imminent. Finally, when he gives in to the influence of his beloved Onufri and transcends the social landscape, Nallbani separates the women’s Byzantine faces from the abstract, sinewy bodies. The piercing gazes and the non-provocative nudity create reverent but anxious imagery that expresses an ache in the current condition but sketches some further possibility, where, perhaps, the emancipation can finally be fully realized. One can only hope that we get to see it and catch Nallbani depicting the newest transformation of an Albanian woman, which he will undoubtedly capture in its sheer power, never for one second allowing the male gaze in. Nallbani, the painter, is always distanced yet involved, open but respectful, insightful, but cautious.

For more content like this sign up for our weekly newsletter

MORE HASAN NALLBANI