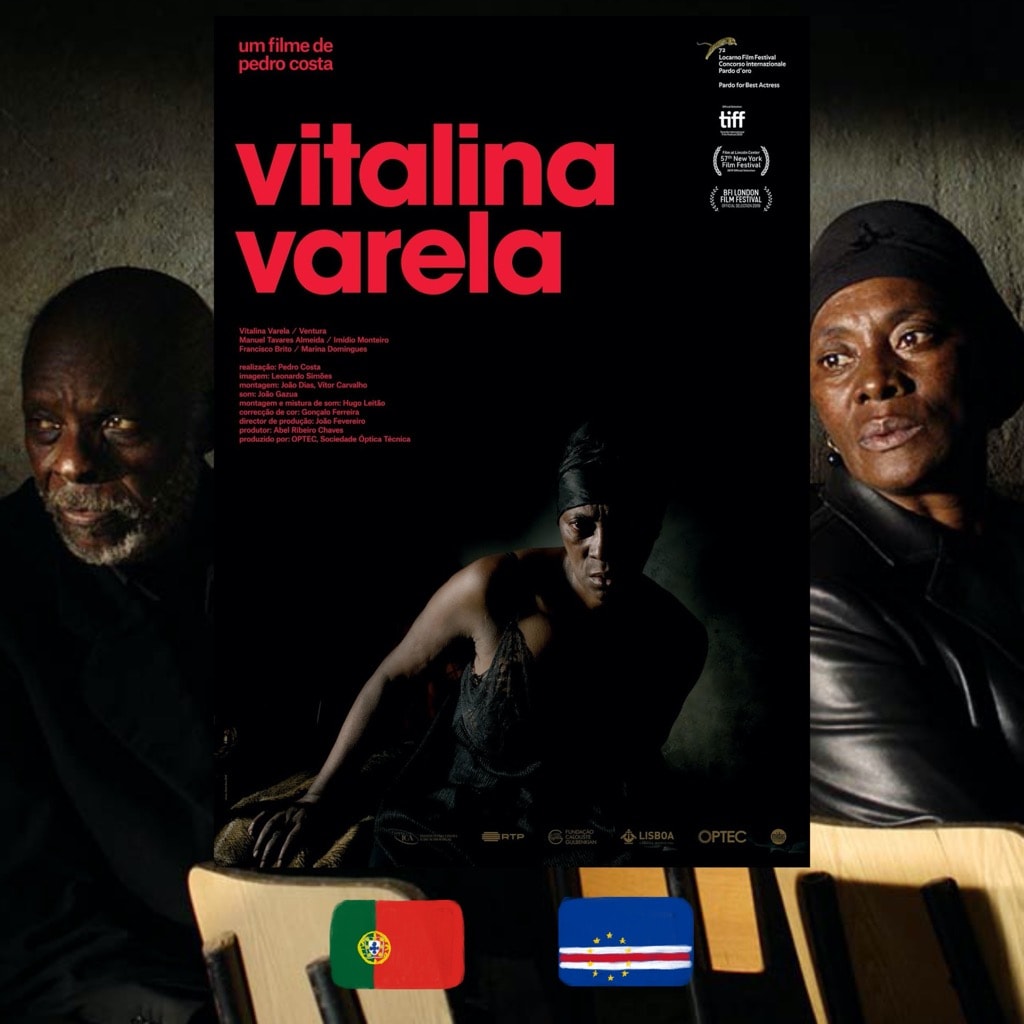

A migrant’s forgotten widow tries to process grief in a Lisbon slum where he used to live: a vigorous, visually-stunning work based on the leading lady’s lived experiences

FROM PORTUGAL and CABO VERDE

WHAT IT’S ABOUT: Vitalina Varela, a woman from Cabo Verde, arrives in Lisbon to see her sick husband Joaquim in the Fontainhas shantytown. He immigrated 25 years ago, and Vitalina had been waiting for an invitation to join him all this time. She is late: Joaquim had just been buried, and his friends inform her she is not welcome. But instead of returning home, Vitalina stays in the tiny apartment haunted by Joaquim’s ghost and tries to make sense of the half a century they’d spent apart. Slowly, Vitalina starts retracing her late husband’s life through interactions with the local landscape and community and familiarizes herself and the reader with the humans lurking in the shantytown like shadows,—among them Ventura, a priest without much of a congregation, who, like Vitalina, is mourning his belief.

WHO MADE IT: Portuguese director Pedro Costa has been making complex films blending drama and documentary elements that heavily feature Cabo Verdeans for the past two decades. His second film, 1994’s “House of Lava,” was about a nurse escorting a comatose man home from Portugal. Then, Costa discovered the neighborhood of Fontainhas, where he’s been filming ever since. The first film based there, “Ossos” from 1997, had the focus on a young mother. “In Vanda’s Room,” which was filmed in 2000 and centered on the life of a woman addicted to heroin, won Costa awards in Cannes, Venice, and Locarno. In 2006 Costa first collaborated with non-professional actor Cabo Verdean immigrant Ventura, who took the viewers on a journey between Lisbon’s demolished slums and housing projects in the film “Colossal Youth.” The pair continued to work together on a couple of segments in anthology films and released “Horse Money” in 2014, based on events from Ventura’s personal life. Vitalina Varela, another non-professional actor, who plays a fictionalized version of herself in the eponymous film, first appeared in “Horse Money,” too. Her arrival to Lisbon to see her husband was first portrayed in “Horse Money.” Afterward, Costa decided to expand on this story in his latest feature, co-writing “Vitalina Varela,” with Varela, since the plot is predominantly based on her real-life experiences. Ventura appeared in “Vitalina Varela” as the priest, and Varela’s son played the role of Joaquim in the flashbacks. “Vitalina Varela” also featured Costa’s frequent collaborators: cinematographer Leonardo Simões, editor João Dias and producer Abel Ribeiro Chaves. The film has had quite a festival run, bringing in numerous awards, including some for Ventura and Varela’s acting.

WHY DO WE CARE: There are many stories about migrants but few that focus on the families that they leave behind. In creating “Vitalina Varela,” Pedro Costa had a more complex goal than just achieving inclusivity, but his film is a stunning portrayal of the opportunity costs to the “better life.” Every single migrant man who comes abroad to seek superior options, leaves behind a woman, a mother, a sister, a wife, who has to bear the burden back home. And it’s quite often that they don’t get asked along, or even seen again, sometimes due to the man getting a new life, sometimes just because returning without having improved is dreadfully hard. When Vitalina Varela in the film tries to find closure through an attempt to become one with the walls of her late husband’s decrepit dwelling, the agony of her alienation is palpable: are those petty shreds what he abandoned her for? And even though Costa is undoubtedly a master, he massively lucked out with Varela, just like he did earlier with Ventura: the dignified suffering of the woman who’s live through the same ordeal as her character in the film, glows in her eyes. No professional actor would ever be able to play this. And the fact that not only does Costa recognize non-professional talent, he also nurtures it by collaborating with his actors and allowing them to become his co-creators, is revitalizing.

WHY YOU NEED TO WATCH: There are many ways in which grief and the disenfranchised experience are portrayed in the film, but very few other films, especially ones that aren’t purely documentary, extend as much unmanipulated grace to the subject matter and those living it. Instead of merely pandering to the viewer for empathy, Costa pushes you into the dark underbelly of the migrant slums and lets the experience verging on the immersive do the groundwork. It’s present from the beginning, where Vitalina Varela steps off the plane, barefoot, having wet herself while crammed in the seat in the neverending flight from Africa, to the last shots, when the film’s haunting imagery and sound have entirely overtaken the viewer’s senses. The film is not merely an evocation of emotion, but a physical amalgamation of pain and othering that’s not easy at all to shake off. But the best thing about “Vitalina Varela”, as well as Costa’s other films, is that they never forfeit their beating, bleeding heart for the sake of formalism. There is much to admire from an aesthetic standpoint: the breathtaking chiaroscuro, Varela’s affecting beauty that films the frames, the non-linear narration and the scenes between Varela and Ventura that verge on the ancient tragedy, all entwine to make the film into an astounding masterpiece of visual poetry. However, the humanity within it, and Varela in particular, is so omnipresent, that it, too, rises above the narrative as a rusty, aching sun, and delivers a sheltering warmth.

Vitalina Varela, 2019

Director: Pedro Costa

For more content like this sign up for our weekly newsletter

WATCH THE TRAILER