After a religious revelation, he became an art sensation in his middle age. Today, Amos Ferguson’s legacy is a testament to why it’s vital to see countries for their marvels and talents, not profits

FROM BAHAMAS

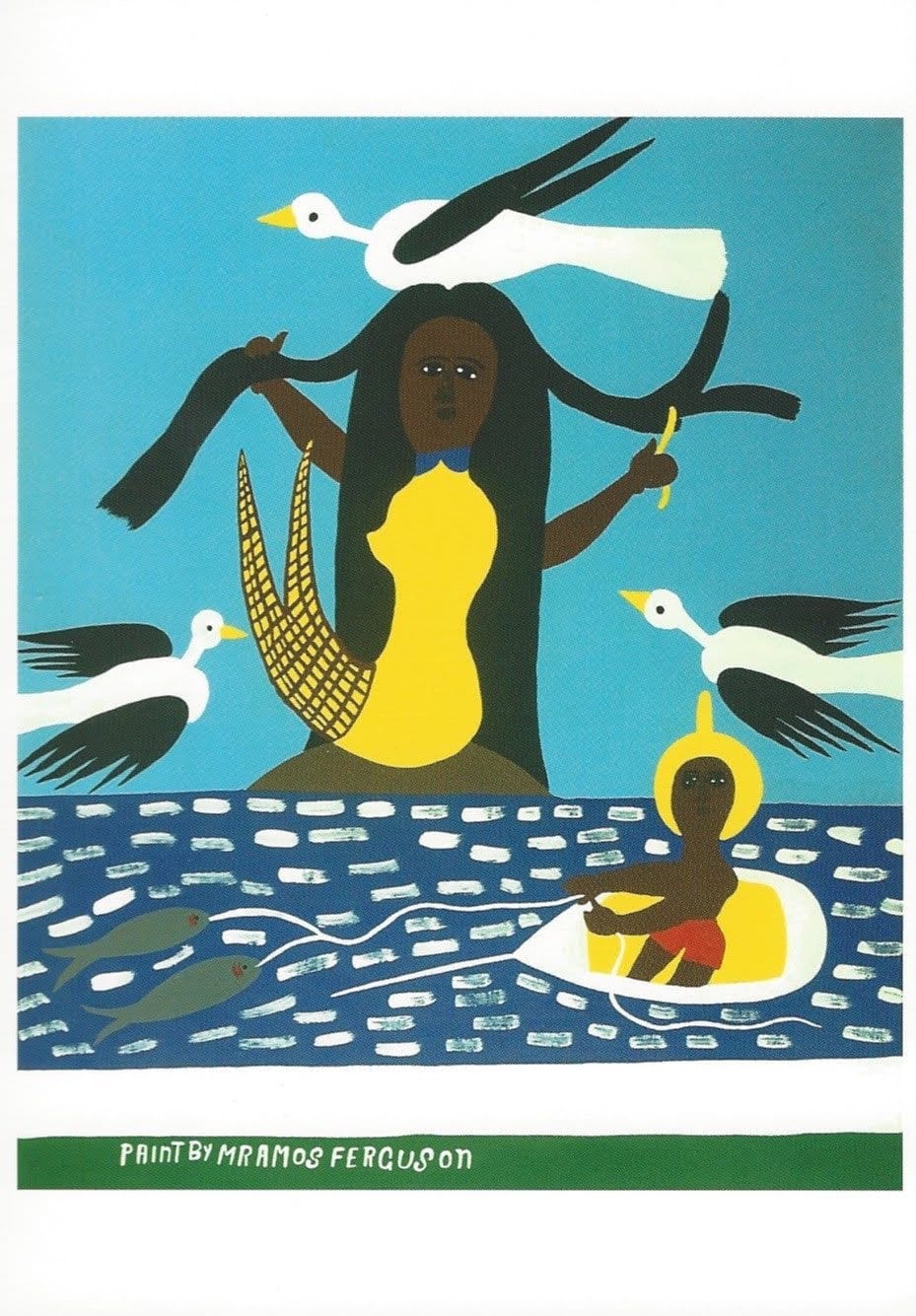

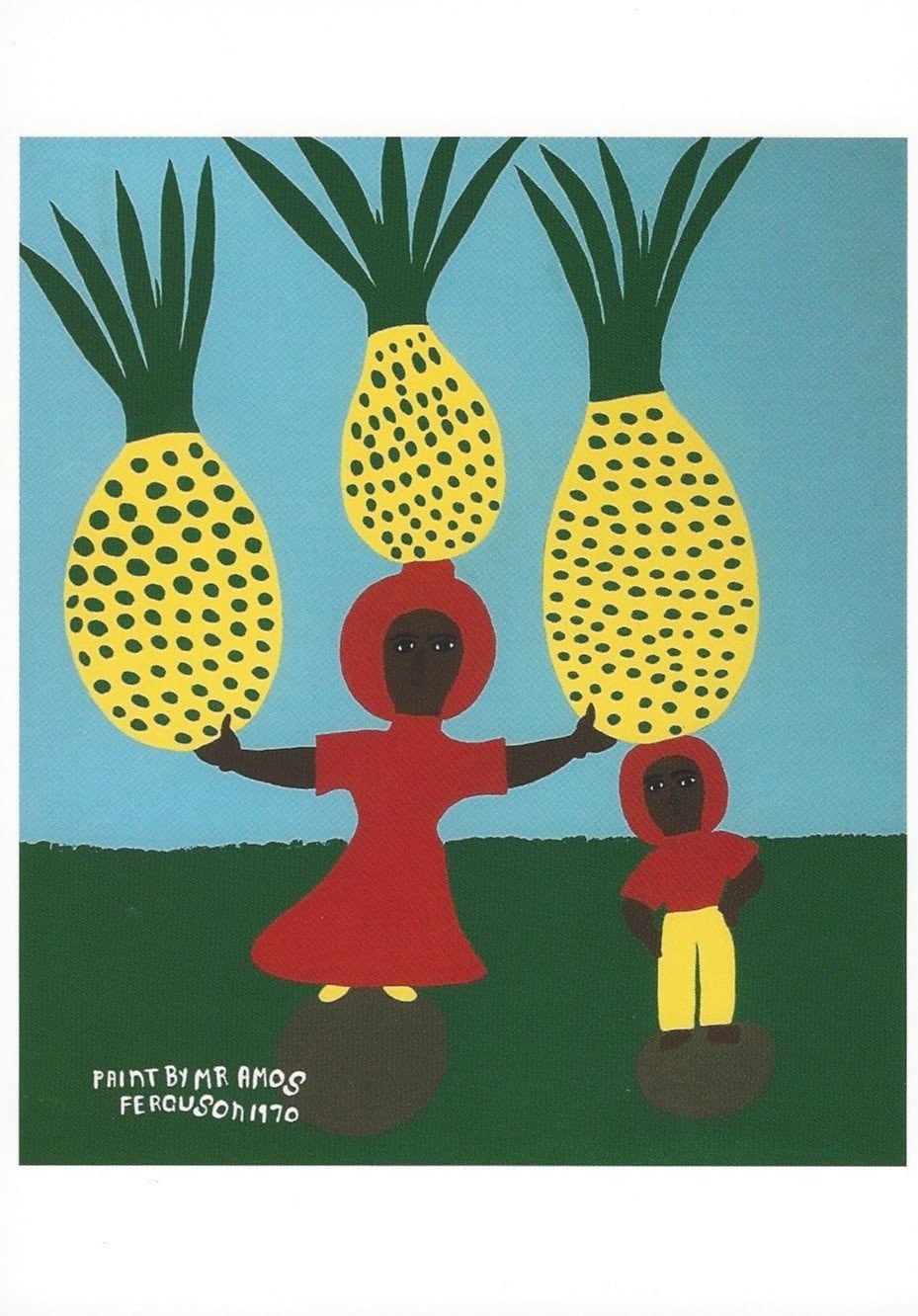

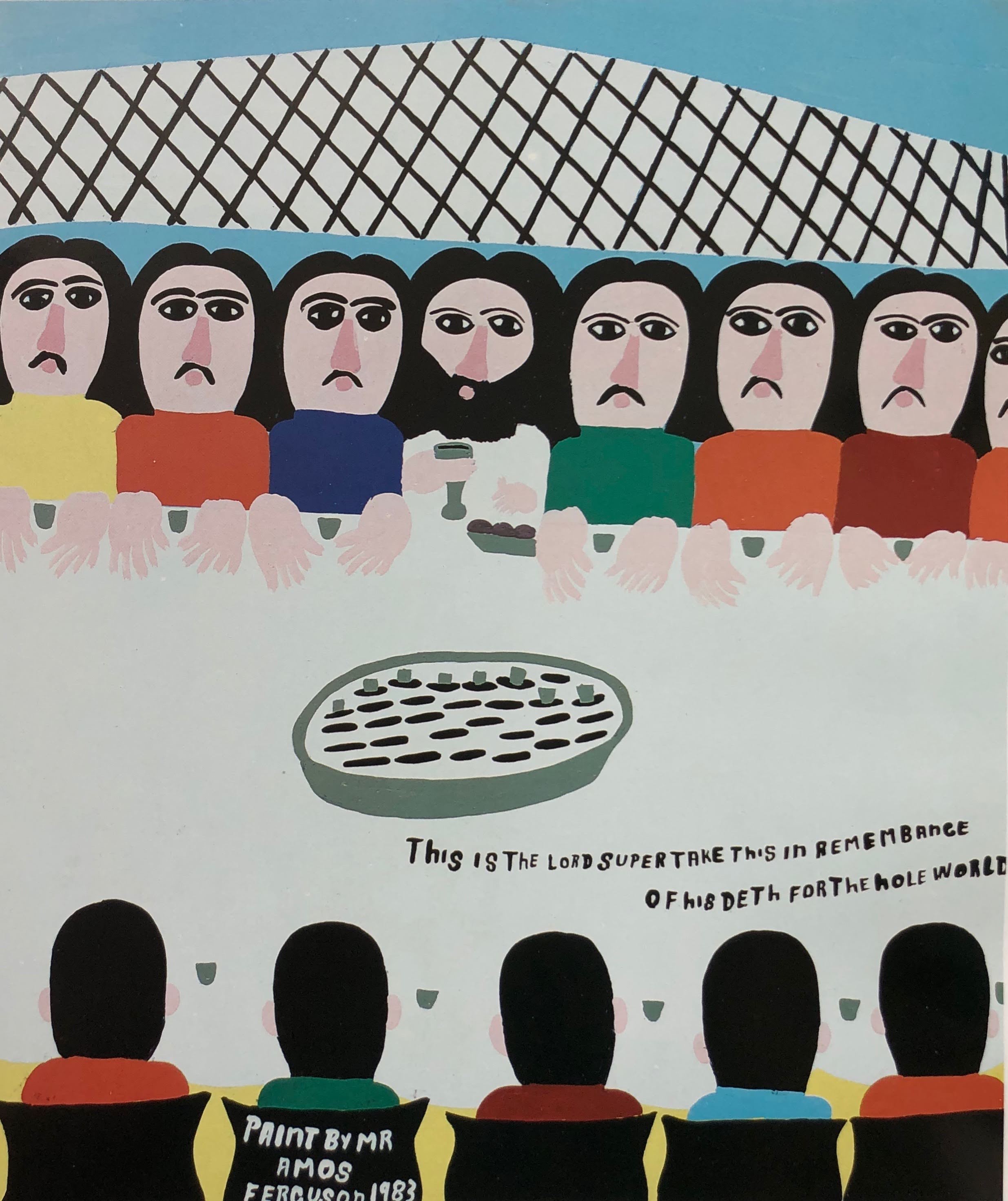

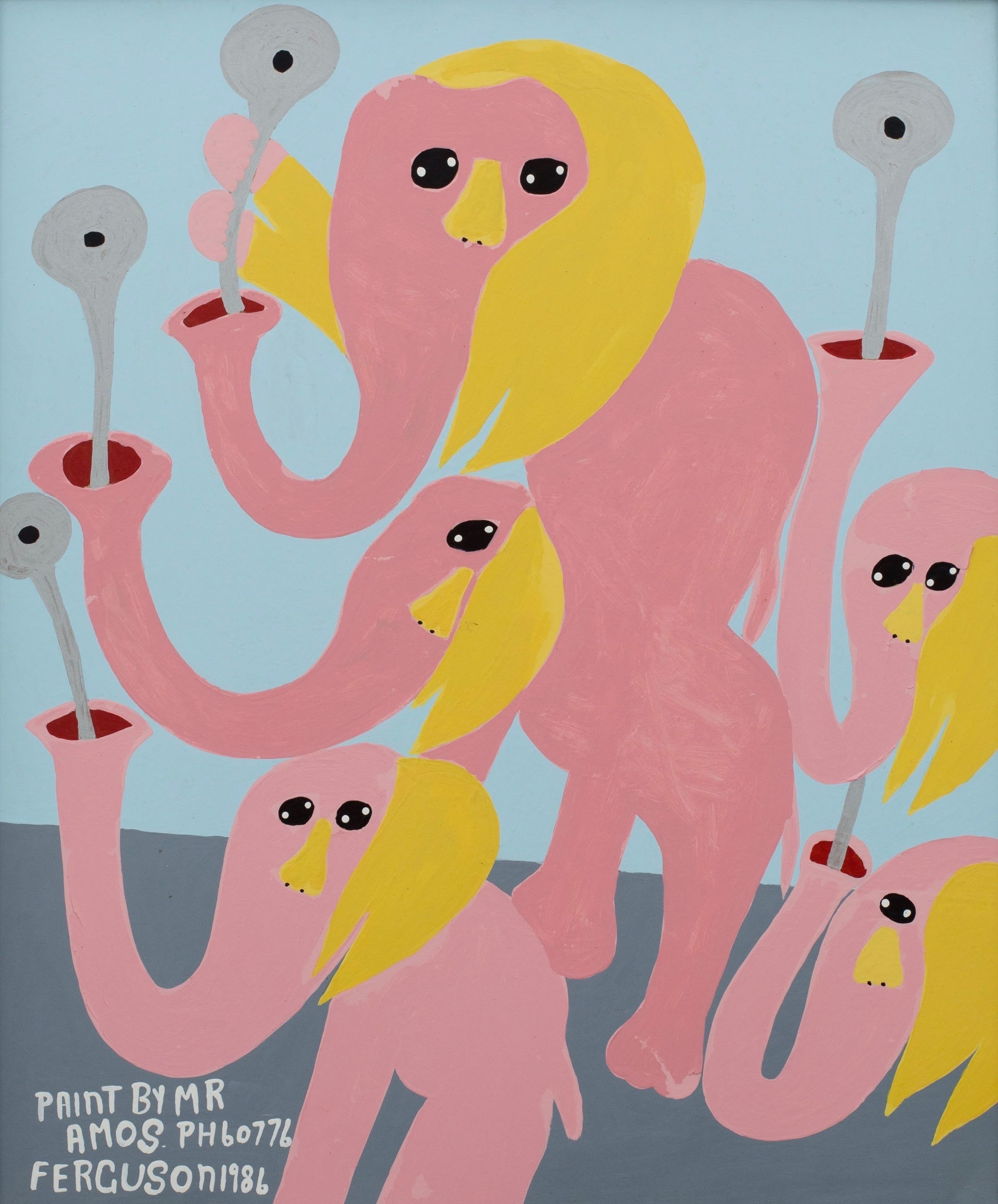

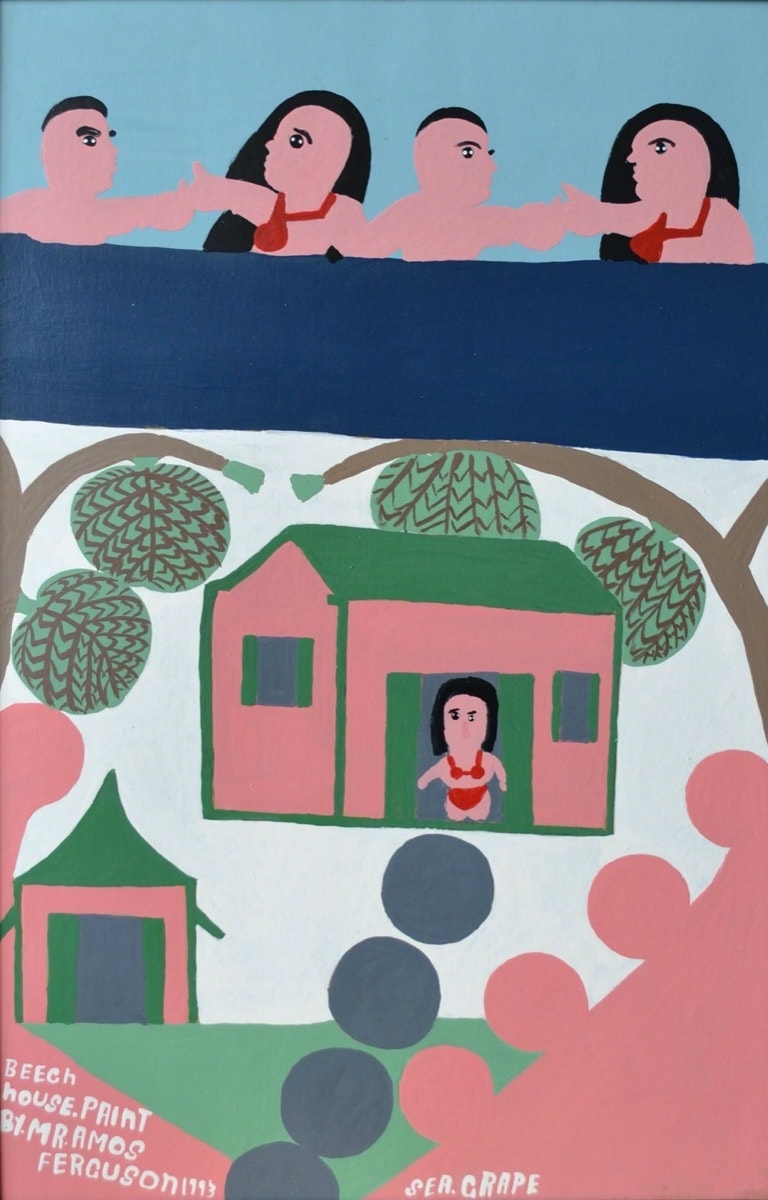

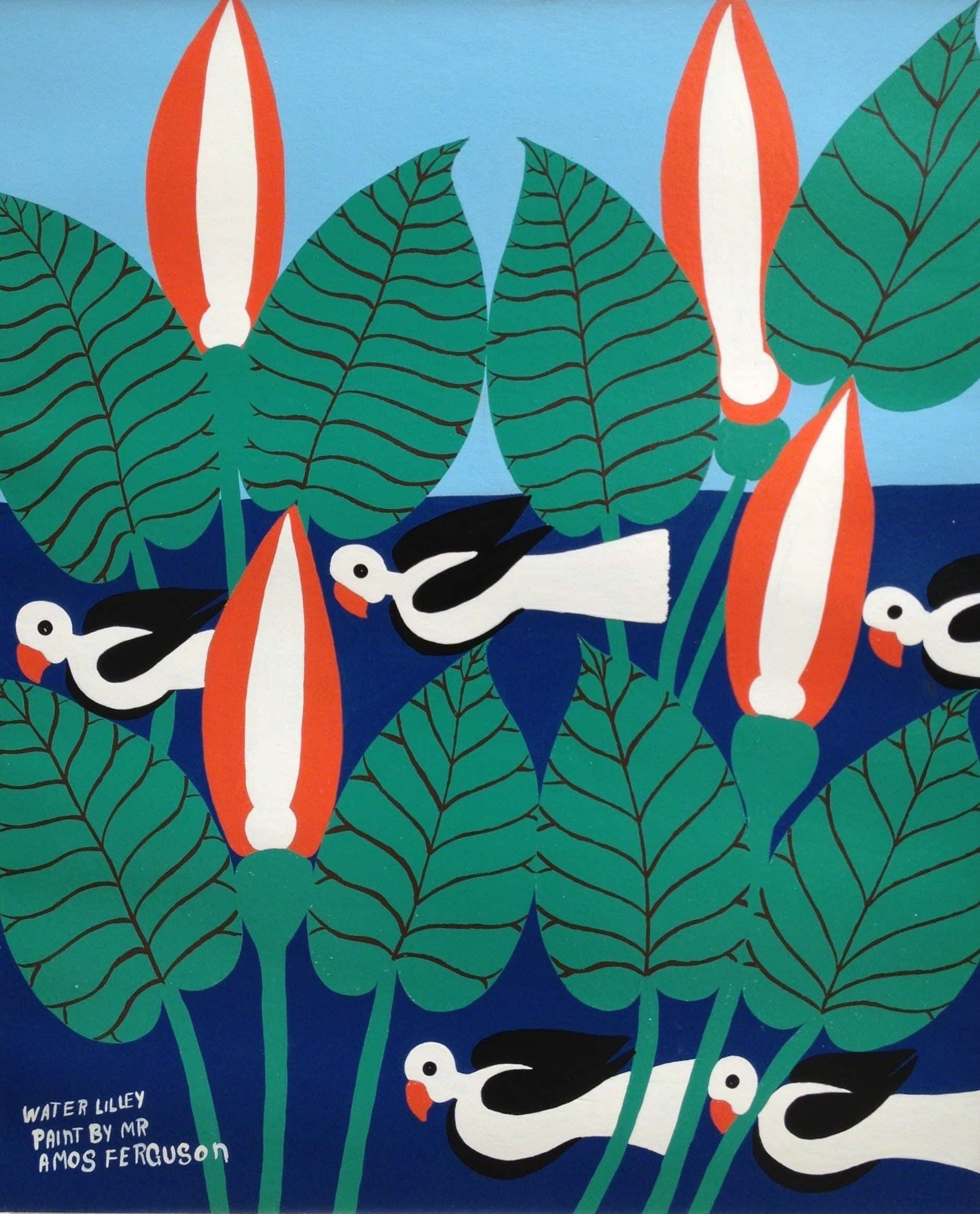

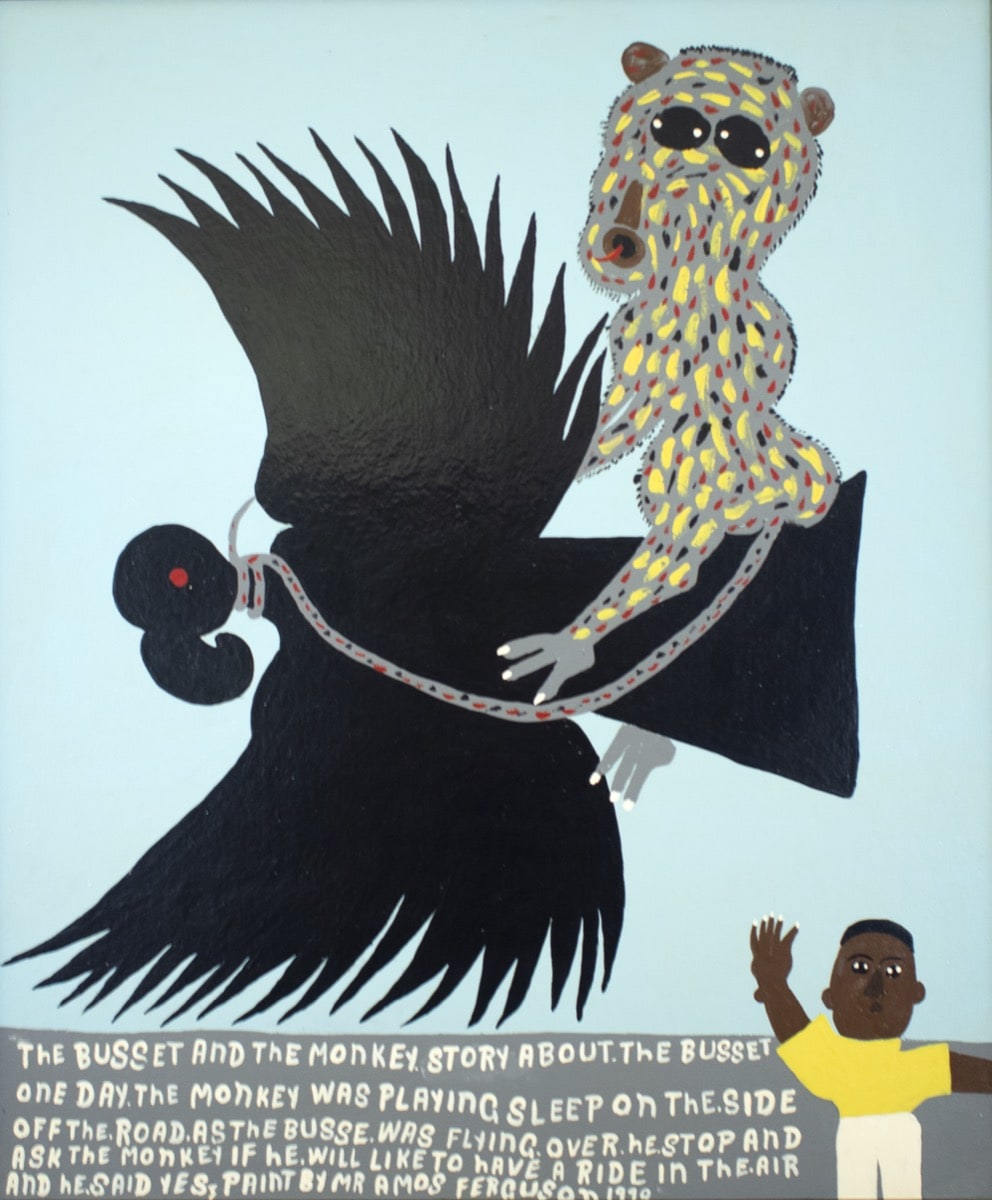

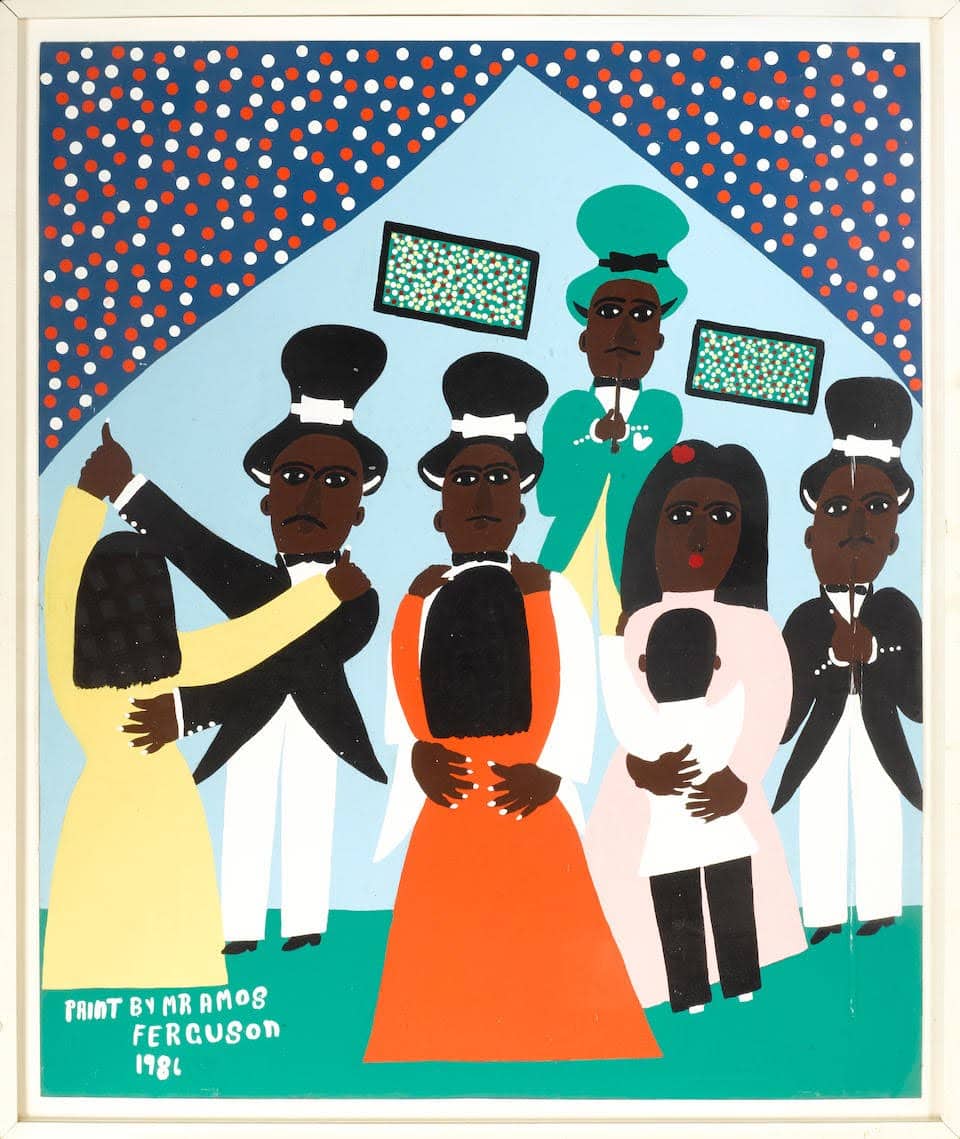

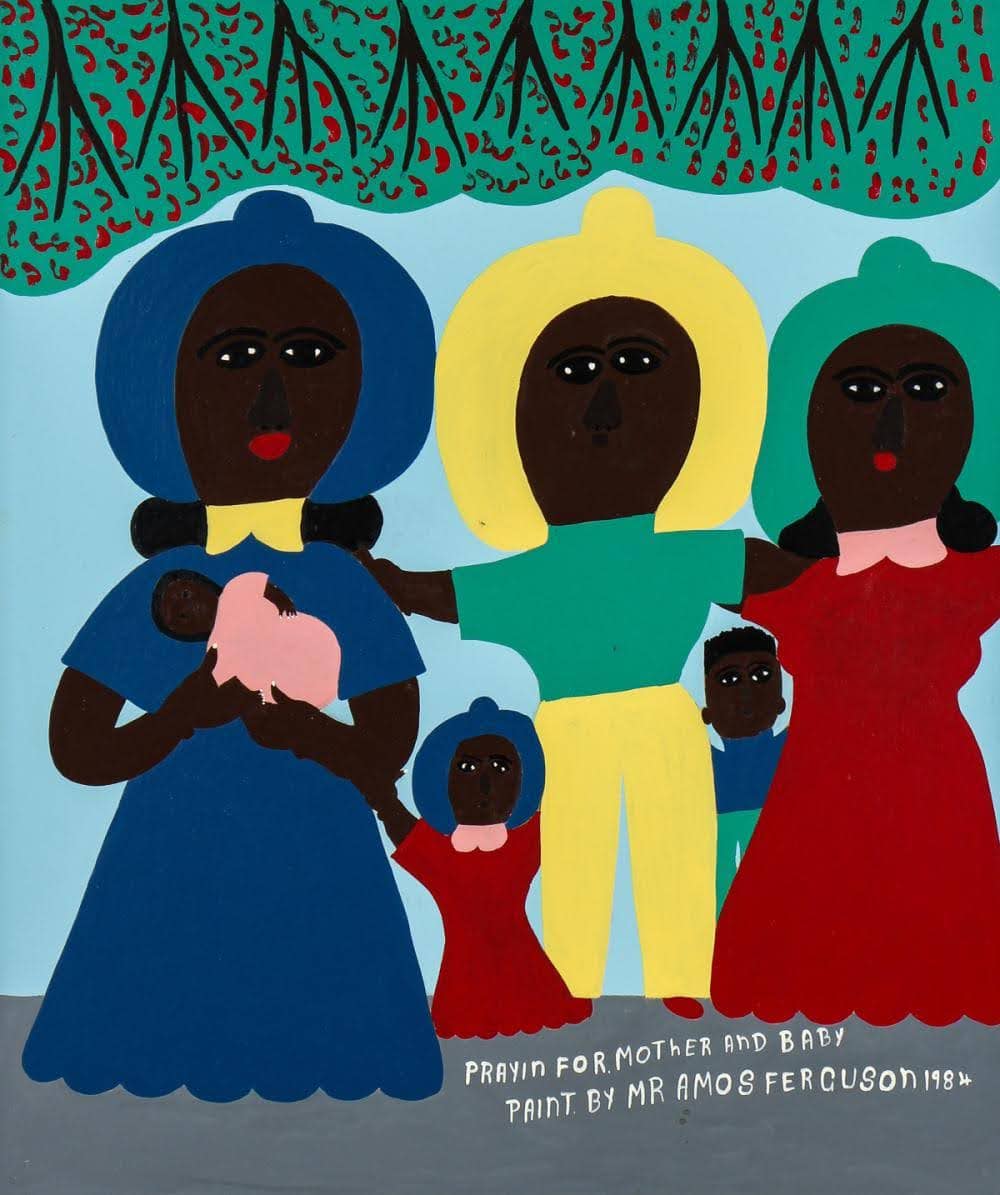

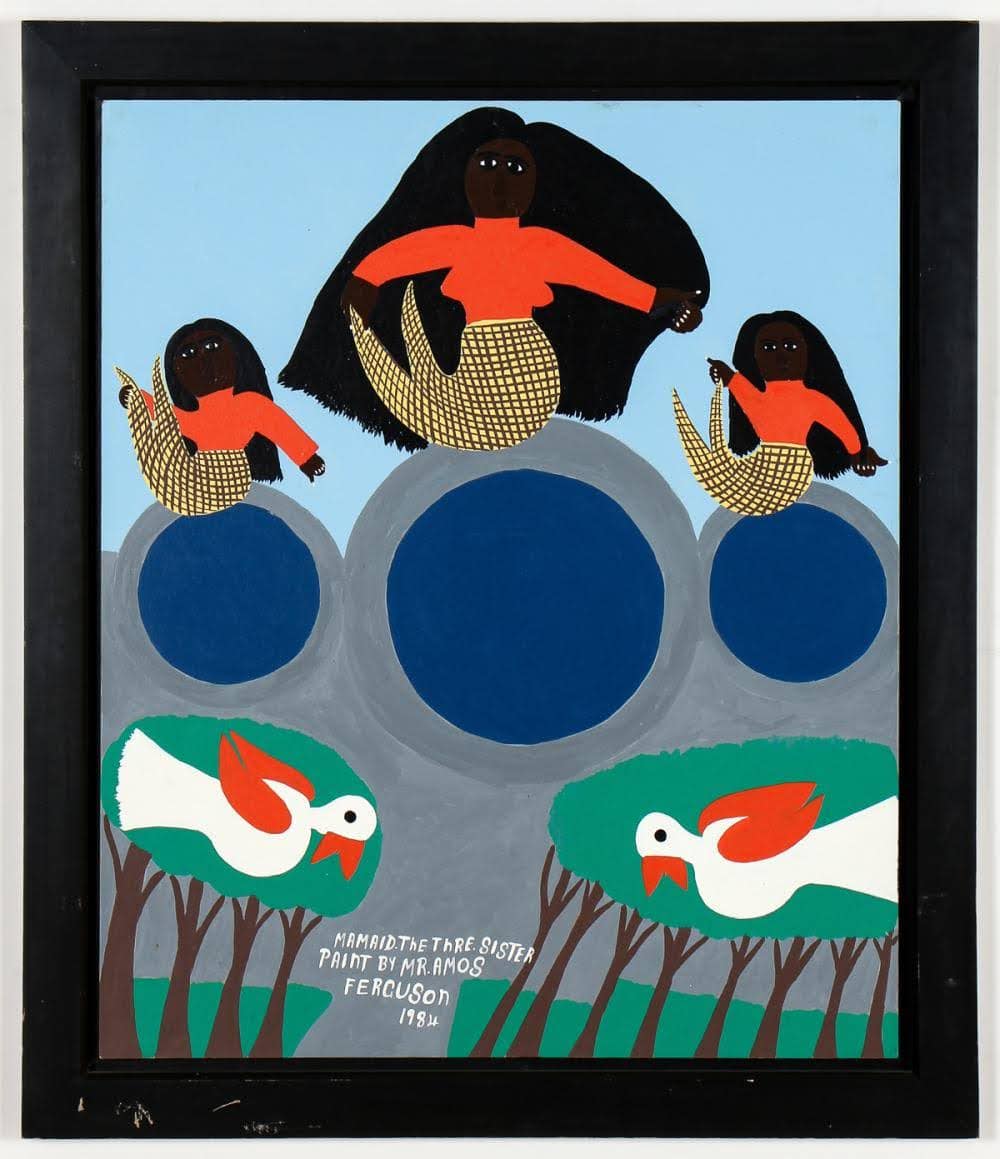

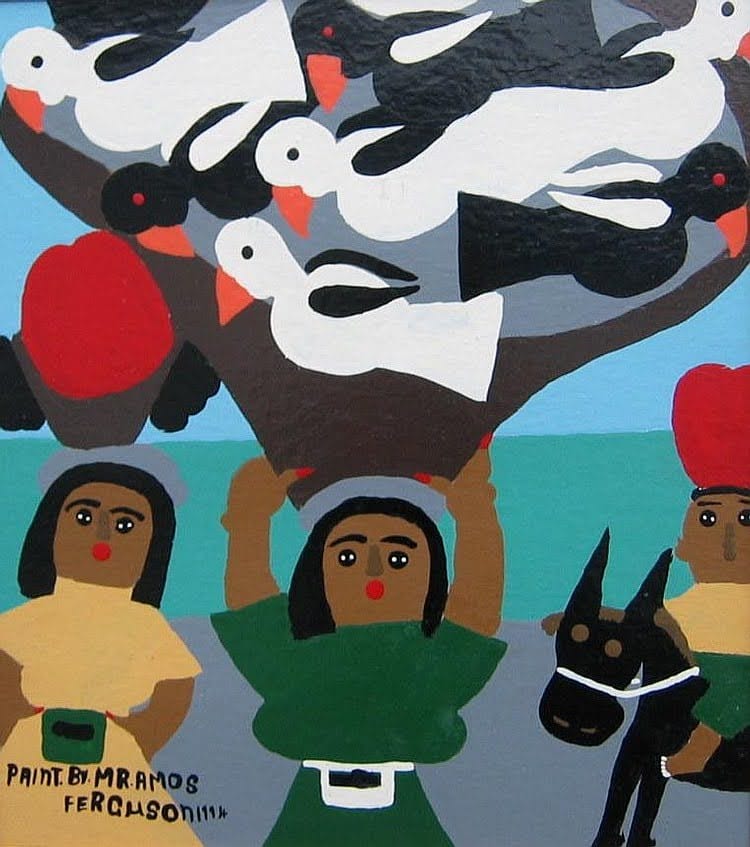

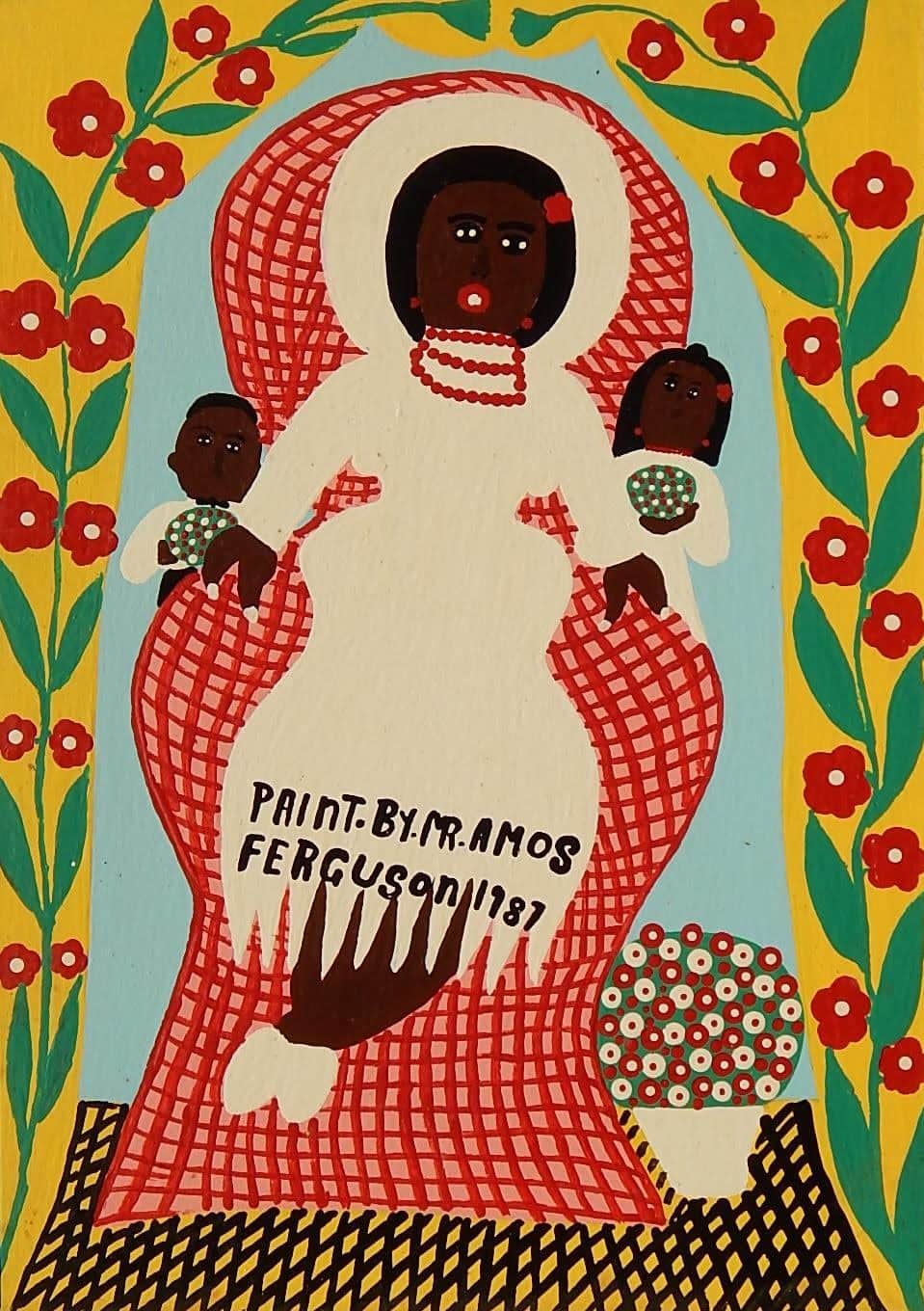

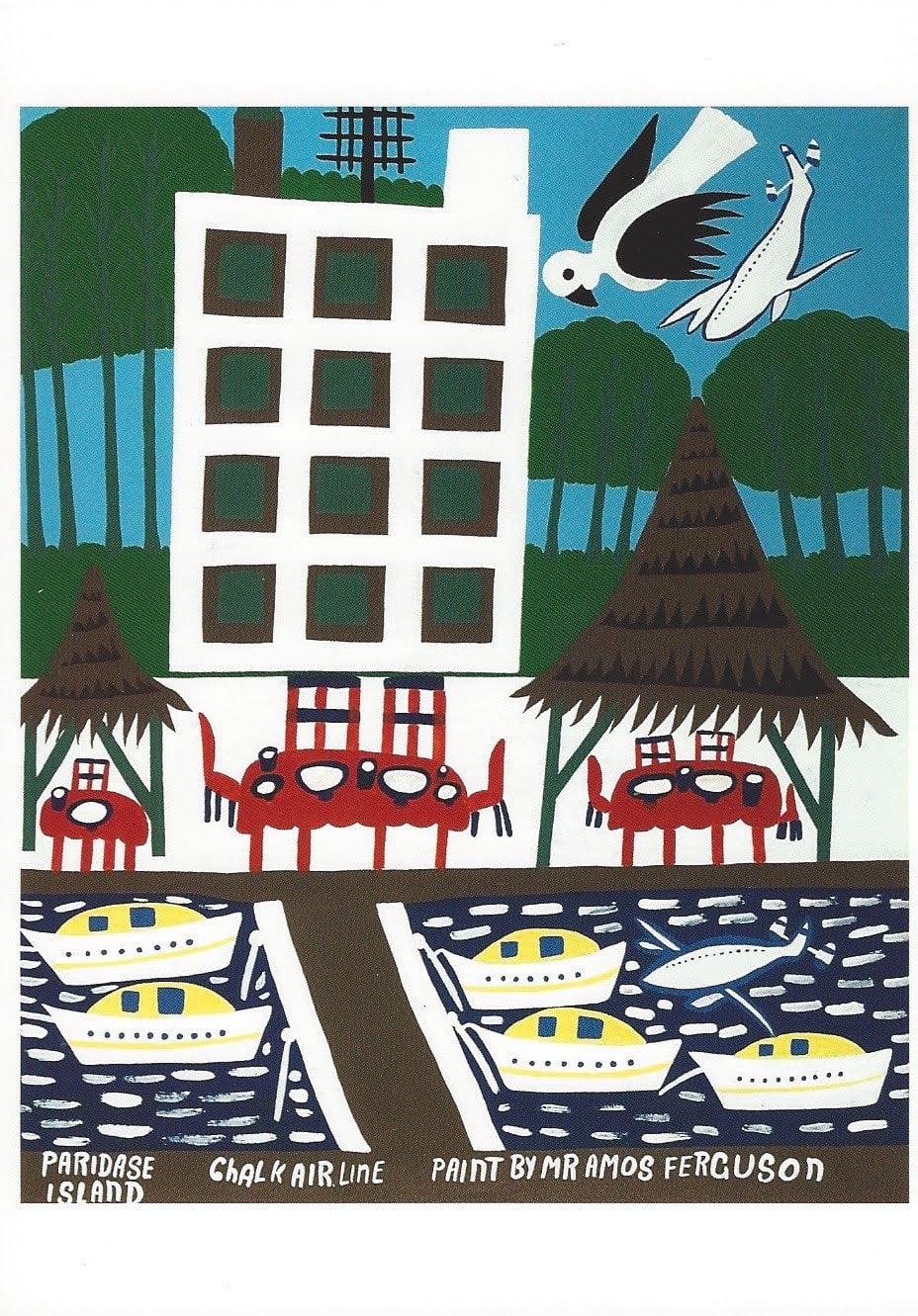

WHAT’S GOING ON: Visions of Bahamian nature, infrastructure, and rights of passage explode in a psychedelic array of colors. Biblical scenes, recognizable and yet made fresh, are transferred to Nassau’s outskirts, with wise, eccentric parables accompanying every one of them. The birds, mammals, and crustaceans, the lush, blooming flowers, and ripe fruit, the pastel-colored dwellings, and the locals, in their finest attire or everyday clothes, are depicted in stark, expressive shapes. Sometimes the forms are so substantial, one might confuse those paintings for cutouts, but it’s upon closer inspection and paying attention to the playfulness of the strokes that it becomes apparent how each part of the works was handpainted with great care. Those are the works of Amos Ferguson, the Bahamian self-taught artist. He became a household name both at home and abroad once he realized that his mission in life was to paint, and took to it prolifically, a wild geyzer of imagination within him never running dry.

WHO MADE IT: Amos Ferguson was born on the island of Exuma, one of the 14 children of a Baptist preacher who doubled as a carpenter. Ferguson grew up surrounded by his homeland’s brilliant nature, the teaching of the gospel, and an understanding of what trades mean for a man’s life. At 17, he left for the capital, Nassau, and used the skills inherited from his father to work with furniture. When World War II came, and the US was suffering from a shortage of labor, Ferguson became one of the Bahamian men to go abroad as a contract worker. He spent a decade as a migrant laborer in Minnesota, Florida, and Virginia. Upon his return, he started painting houses for the wealthy Nassau-dwellers.

Amos was in his 40s when his nephew George came to him and told him about the vision he had. In it, the Lord’s voice firmly stated that he had given one of George’s relatives an artistic talent, which they had been wasting instead of making a living out of it. Amos immediately knew that he was the relative with the talent in question. The divine message and his nephew’s words only reiterated something that Ferguson has long been wondering about, and the need to dedicate his life to art crystallized. The next half of his life was spent ceaselessly creating. First, he merely carried some art supplies in his pockets to capture the moments of inspiration as they came. Then, in his 50s, Ferguson retired and began painting full time, as well as sending his works in the bay. It was then that he met Bea, a basket weaver, who later became his wife. She was his biggest champion and sold Amos’s works in the straw market, alongside her baskets and handmade dolls. This is where a wandering American art-collector Sukie Miller discovered them and fell in love with their whimsical yet profound contents. And when she told her American friends in the art world about Ferguson’s talent, an international art career was launched.

WHY DO WE CARE: Once you see Amus Ferguson’s works, especially lined up in vast numbers, it’s hard to resist the urge to see more, until everything around you is full of his delightful visions. And it’s no surprise that when Sukie Miller first saw these paintings, she immediately wanted to show them to her friend, Ute Stebich, who was an established Caribbean art dealer in Massachusetts. As Stebich shared Miller’s fascination with the works, the two women traveled back to the Bahamas to thoroughly photograph Ferguson’s works and introduce themselves. The four of them became fast friends, and the American women even attended Ferguson’s wedding to Bea sometime later.

After taking stock of Ferguson’s oeuvre, Miller and Stebich brought the photographs to the curators of the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, Connecticut, hoping that they’d want to purchase some for the collection. However, the curators were also so impressed that they immediately organized a solo exhibition for Ferguson. This led to further exhibits and commissions across the world, as well as representation by another Westerner who fell in love with his works: Laurie Ahner of the St. Louis-based Galerie Bonheur made his works the center of her gallery’s practice. Meanwhile, the Trinidadian-American actor, dancer, and artist Geoffrey Holder, who is best known for his tenure at New York’s Metropolitan Ballet and playing the Bond villain Baron Samedi, was proud to call Ferguson his friend.

But most importantly, Ferguson’s rise to prominence abroad also meant recognition within the Bahamas. Not only did more people start regarding his works as important, but even the government decided to invest in it: the country’s two ex-prime ministers, Lynden Pindling and Perry Christie of the PLP party, were big fans, who allocated funds for Ferguson’s first solo exhibition in the Bahamas, at the Central Bank gallery.

WHY YOU NEED TO PAY ATTENTION: Everything in Ferguson’s life and art is linked to the role that the Bahamas has played and keeps playing in the world imagination, and it’s only fair that we begin to see the island as a source of talent, vision, and nature that needs to be protected, not a tax haven or fancy resort destination. Even though the Bahamas has been an independent nation for almost half a century, colonization continues. Now it is not through slavery or plantations, but through the exploitation of the islands by major world economies, the IMF and the WTO, as well as private companies, such as Disney, which have been absorbing the country’s islands and polluting the waters with their cruises. The story of Amos Ferguson’s rise to artistic prominence is one of the few examples when the world appreciated the Bahamas for what its people could create instead of exploiting and utilizing them for profit while enforcing a highly segregated rule on the islands.

Amos Ferguson has been dead for over a decade now, but his heritage lives on. It’s in the street where he used to live, previously known as Exuma street, but now proudly carrying the name of Exuma’s most exuberant export. His neighbors, who still live there, fondly remember Ferguson for his kindness and eagerness to help with any hardship. And the many works that he created populate people’s and museums’ collections everywhere: from the more traditional paintings on cardboards that Ferguson snatched from Bea’s basket weaving supplies to the various glassware, conch shells, and even paper scraps. As boundless and rousing as the nature of his homeland, the entirety of his creation seems to exist as a parallel world. There, not only the life of Jesus continues, but the gulls, the flamingos, the monkeys, and the crabs all parade around in pristine conditions. And the people of Bahamas walk about proud, the emperors of their domain, always celebrating their earthly glory or the festival of Junkanoo—and as Ferguson’s immense talent shapes the narrative, they know no hardship and see no shadow.

You can check out a catalog of Amos Ferguson’s selected works here.

MORE AMOS FERGUSON