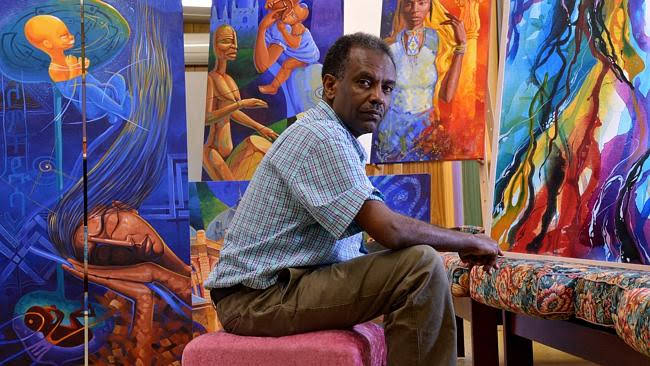

He became an artist while struggling for his country’s self-determination as a young man on the frontline of the liberation movement. Then he lost Eritrea again but recreates it in imposing paintings

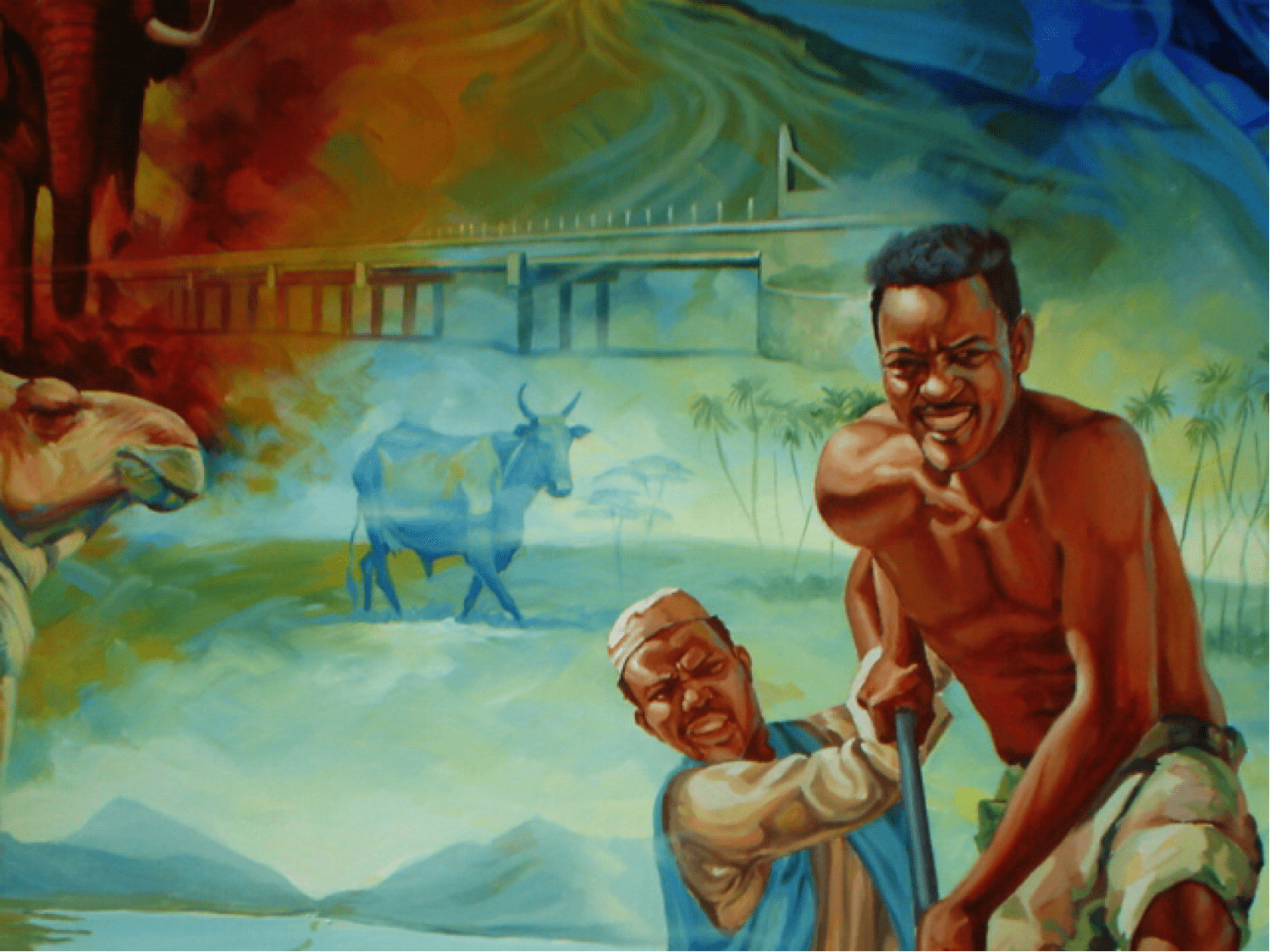

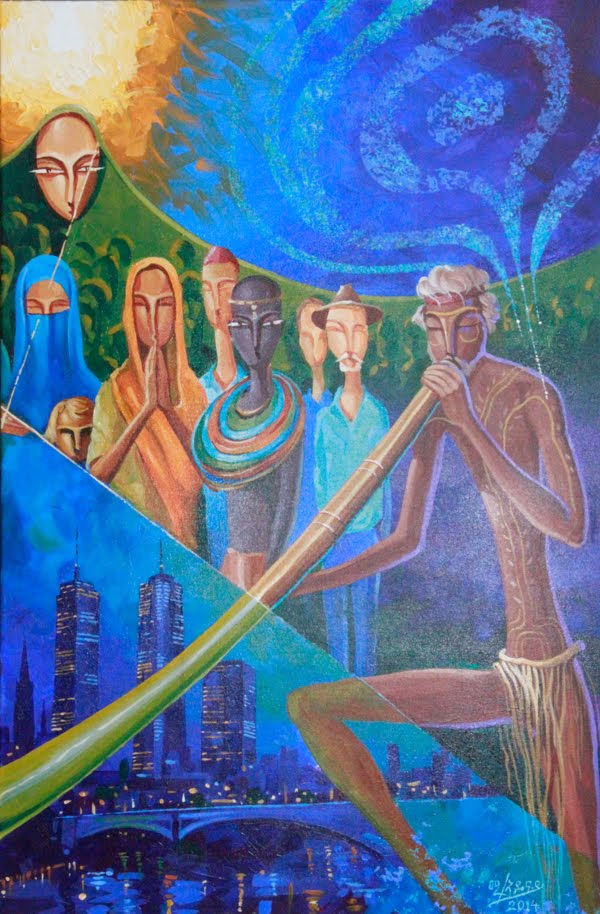

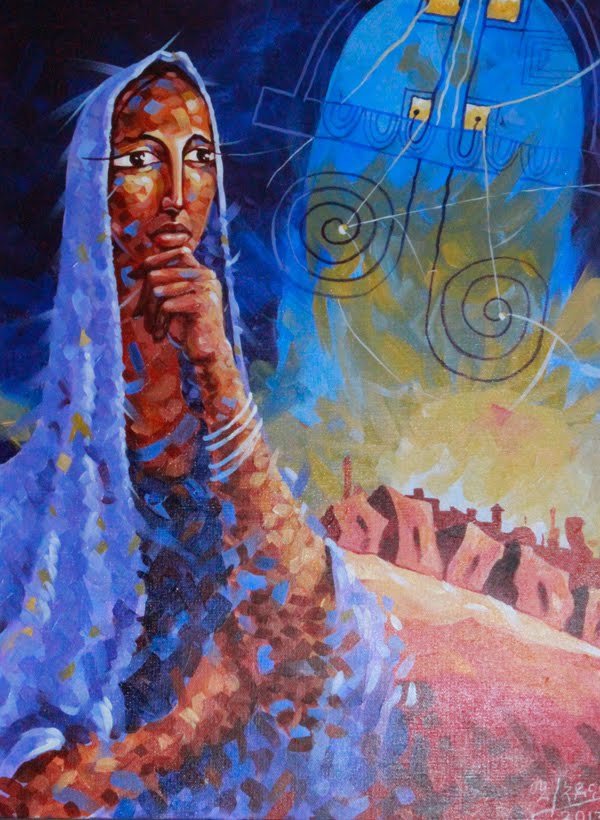

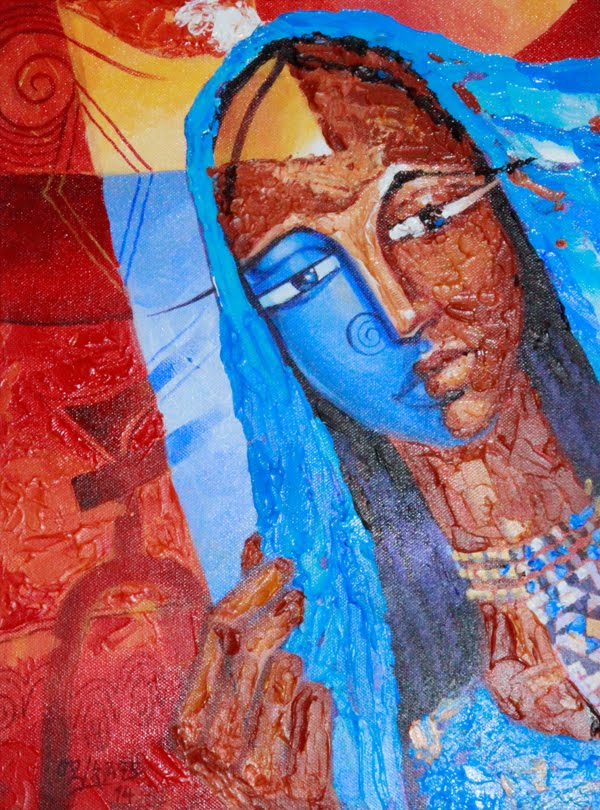

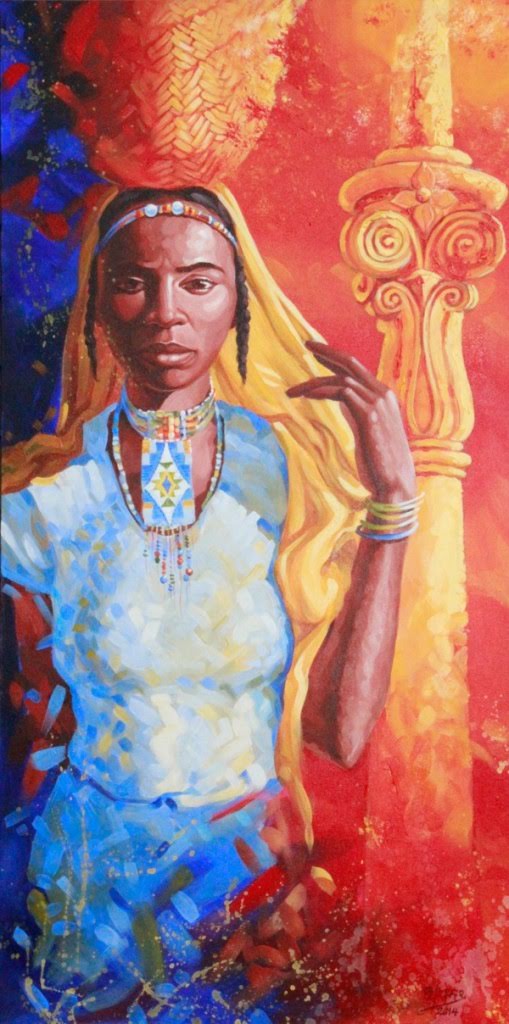

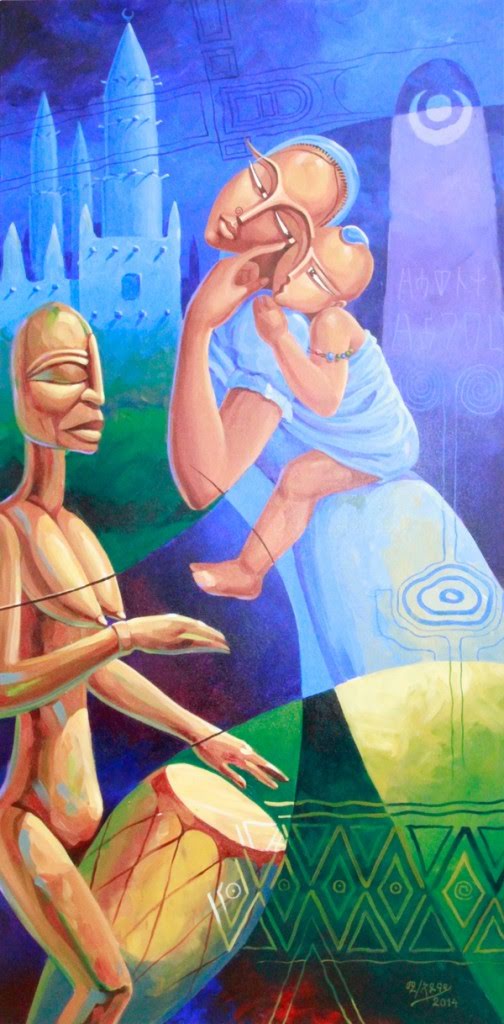

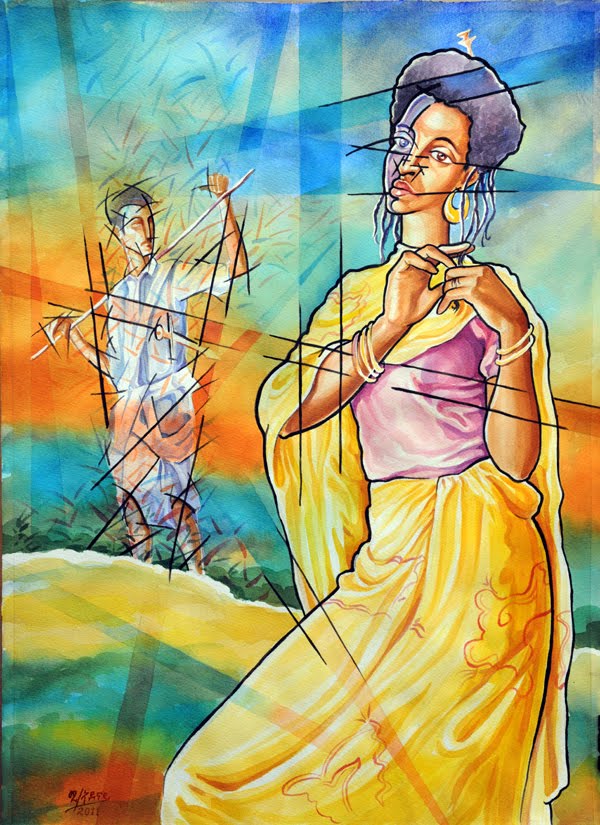

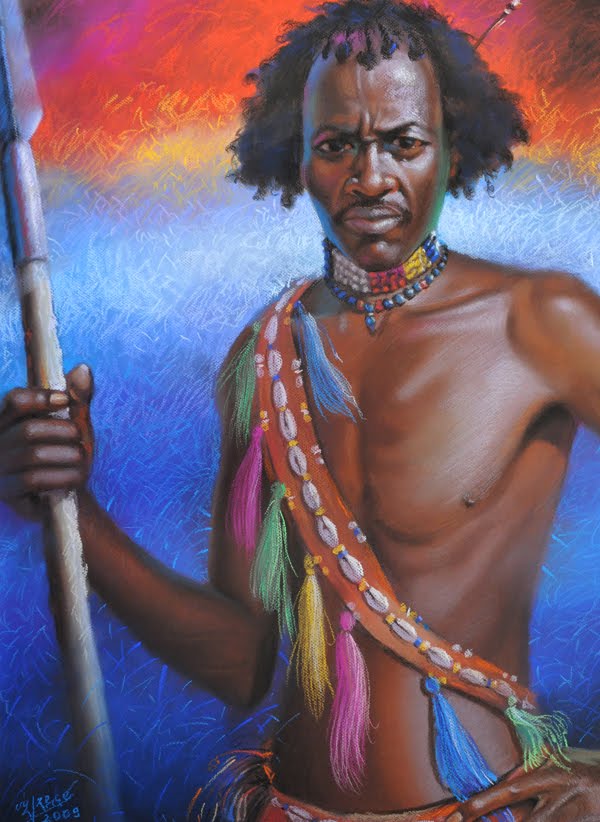

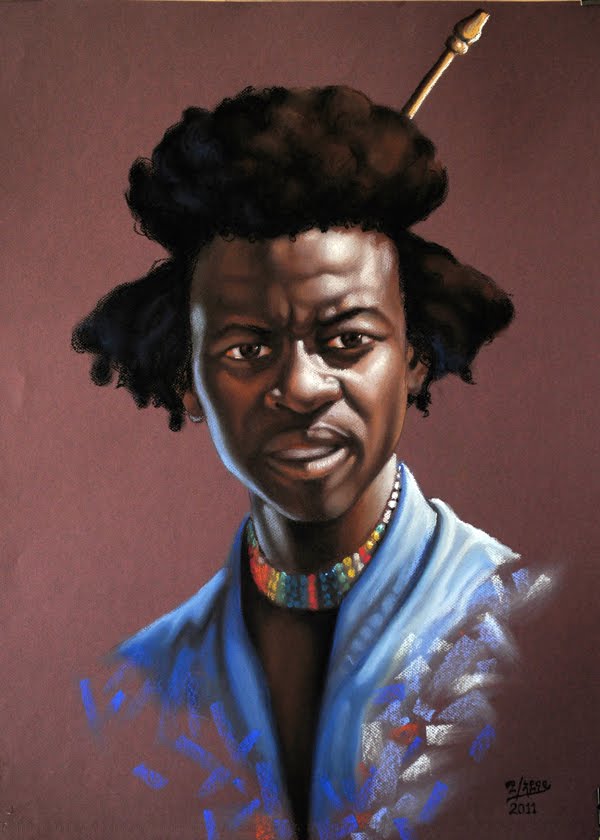

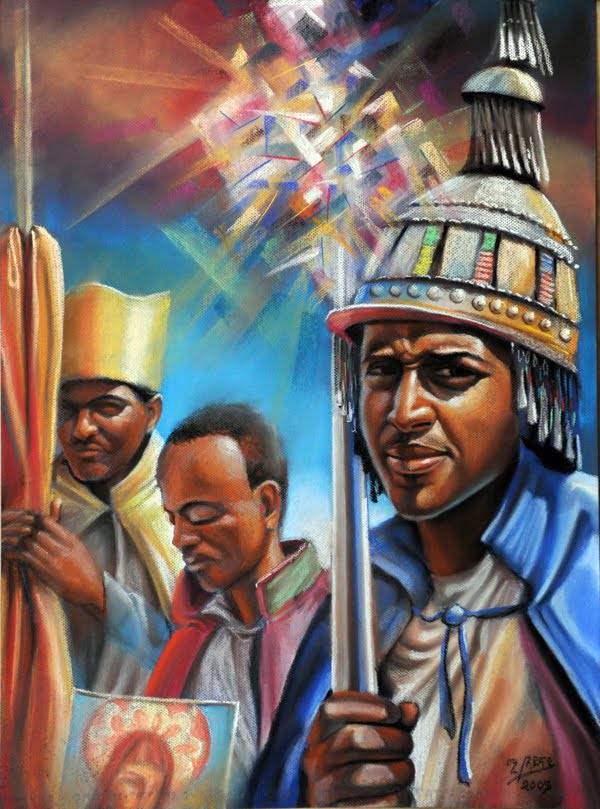

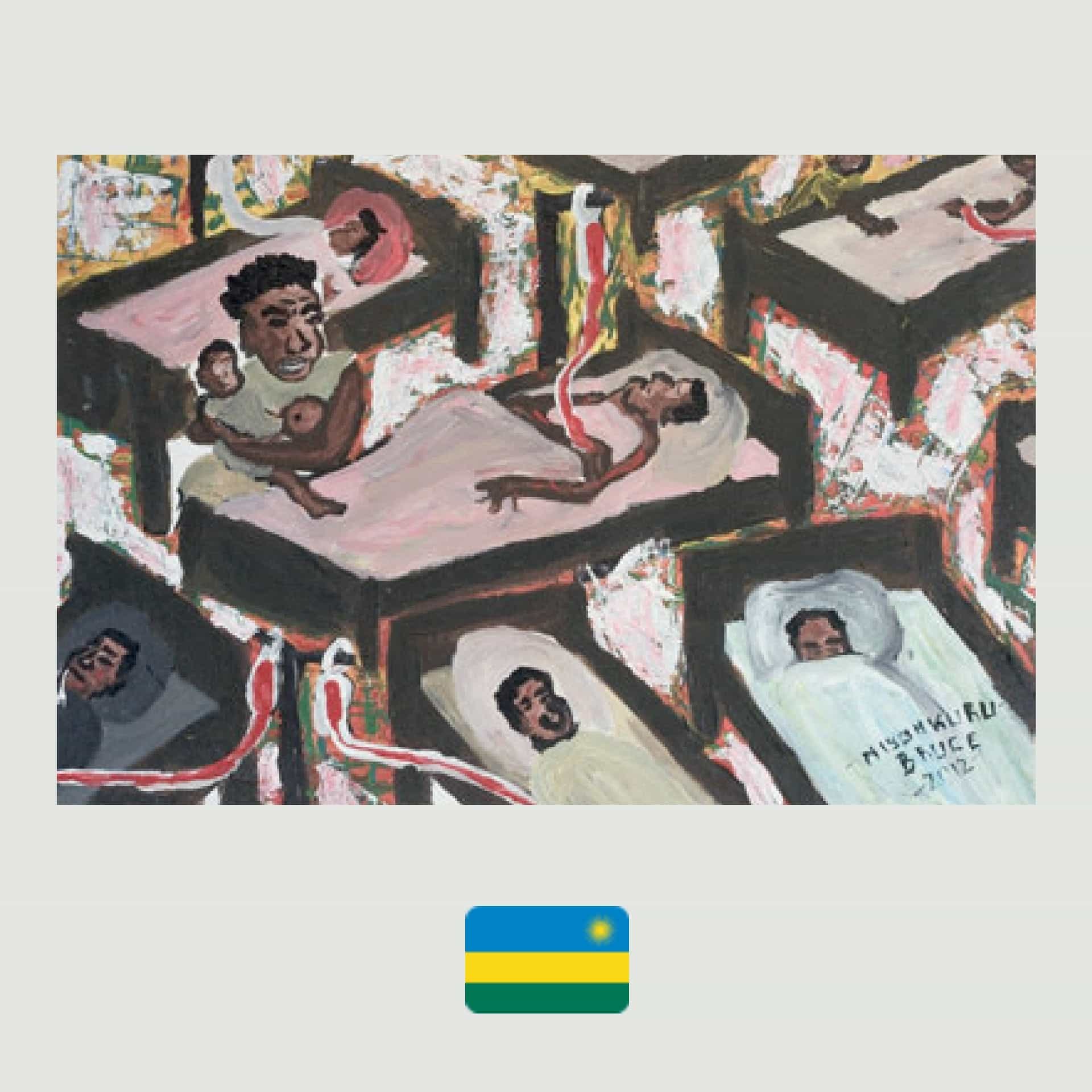

WHAT’S GOING ON: Beautiful black people, sometimes with elaborate traditional hairstyles, clad in garments and jewels, or dressed simply as liberation soldiers, are central in busy, subdued, or multi-hued scenes. Some of the artist’s works are excellent examples of black social realism. There are no exaggerations, no abstractions, just the quiet dignity of struggle on the faces of women guerillas; men celebrating the planting of the Eritrean flag; or working-class citizens navigating the desert landscapes alongside the camels who have sly, all-knowing smiles on their lips. Then, the figurative gives way to expressive stylized imagery, where the flourishes of Charles Wilbert White meet the transcendent geometry and the Goya-like symbolism of the Byzantine era, repurposing the motifs of Coptic devotion to show the struggle of a people in a country that’s adored but had to be abandoned. Those are the paintings of Michael Adonai, Eritrea’s leading artist, who was raised in the bosom of the country’s revolution, found disillusionment on the path to liberation, and then had to flee altogether. His unique manner that merged his roots in Eritrea’s lowlands with the incomparable style inspired by the Coptic Orthodox Church’s art has earned him instant recognition. It has also provided his audience with original looks into the visual landscape of the inspiring but secretive country.

WHO MADE IT: Michael Adonai was raised by his older brother Berhane, an artist and revolutionary. At 14, he followed Berhane to join the Eritrean People’s Liberation Front, and a large part of his life was dedicated to fighting for his country’s freedom in the Eritrean War for Independence. Following in his brother’s footsteps in the choice of profession, too, Michael Adonai had been interested in art since he was a small child. He was happy to receive an art education with the EPLF Cultural Establishment, a pioneering endeavor in the country, where professional visual artists taught the younger generations. By the 1980s, Adonai had become one of the nation’s leading artists; his works often centered around the revolutionary ideals. However, as EPLF was taken over by Isaias Afewerki and experienced the ideological shift from Marxism-Leninism to nationalism, Adonai retreated from participation in the movement and moved to the Eritrean Highlands. There, Adonai first encountered the Coptic church and its polychromous art and architecture, and it became a grounding principle for his artwork in the years to come. In addition to his painting, Adonai is also an accomplished fiction writer in his native Tigrinya language.

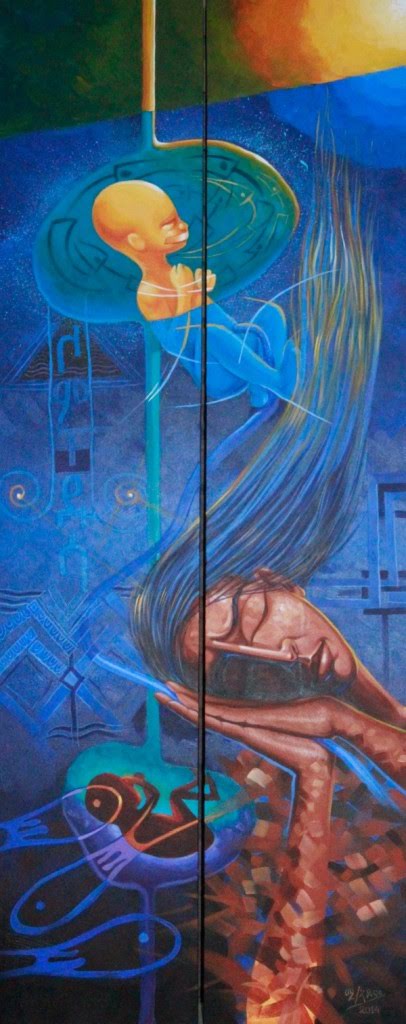

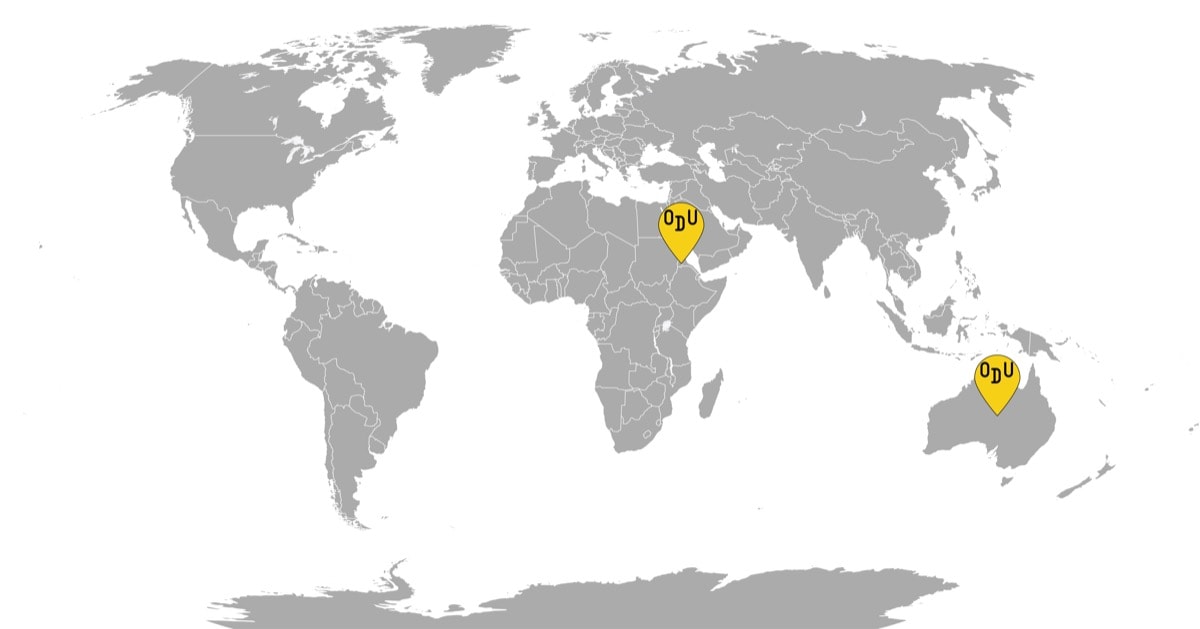

WHY DO WE CARE: Adonai works on the intersection of reality and an aspirational vision of Eritrea that he had struggled for during his years in the army. However, his work is also informed by the artist’s separation from his beloved homeland. He became one of the many refugees that left Eritrea in the 2010s, alongside large parts of the country’s military, Olympic athletes, two soccer teams, and vast amounts of ordinary citizens. Adonai now lives in Wyndham in Australia, and his work is primarily centered around his identity as a refugee, while also consistent with his origins. He finds inspiration in the splendid tapestry that is Eritrean identity: the multi-ethnic, multi-religious country emerges in his paintings as a sort of blissful, green space full of resilient people that is, none the less, continually evading the grasp. Adonai has been covering the journeys of Eritrean refugees, as well, with one of his most striking paintings dedicated to two of the victims of the refugee boat that claimed the lives of 359 refugees in Lampedusa in 2013. A mother who had just given birth to a baby, drowned, and their lifeless bodies were later retrieved, still connected by the umbilical cord. Adonai’s portrait of the two is a melancholy yet dramatic scene, in which the gently sleeping figures of the mother and child seem to be floating away into the stratosphere, away from the cruelty of the planet where a peaceful life was impossible for them.

WHY YOU NEED TO PAY ATTENTION: The power of Adonai’s works lies in the way he uses the context of his dearly-beloved country and the melange of its rich cultural traditions to fuse them into a futuristic vision, a Wakanda of sorts. In his geometrically ordered but masterfully fluid arrangements, where the starkness of lines evokes collages and cubism, all the earthly passions, such as grief or pride, seem to exist on an abstract scope, allowing distance, but also divination of a possible, better future. Highly decorative backgrounds, full of little signs that look like cheering people, birds in flight, or the hammer and sickle, are juxtaposed against many raised hands, spectral visions of urban growth, and arches of human heads that bridge struggle to progress. Against them human figures, varied, somber, introspective and humble, peaceful but spirited, and from stark realism, Adonai often goes into deep abstraction, rendering the figures in a dazzling Byzantinean anime. It’s hard to place his Coptic masterpieces in a particular era or place because they bring together a Space-age imagination with traditional Eritrean ornaments, and consist of paintings that are fresh, inspiring, yet eternal and wise. Adonai’s works allow for an idea of an Eritrea that may not exist now in the tangible reality but is real and possible as long as its most celebrated artist can envision it. A master of depicting the purity and transcendency out of anguish experienced on the way to deliverance, Adonai creates a lasting heritage through art where his political pursuits weren’t fruitful: a sad, but resonant and resolute practice.

For more content like this sign up for our weekly newsletter

MORE MICHAEL ADONAI