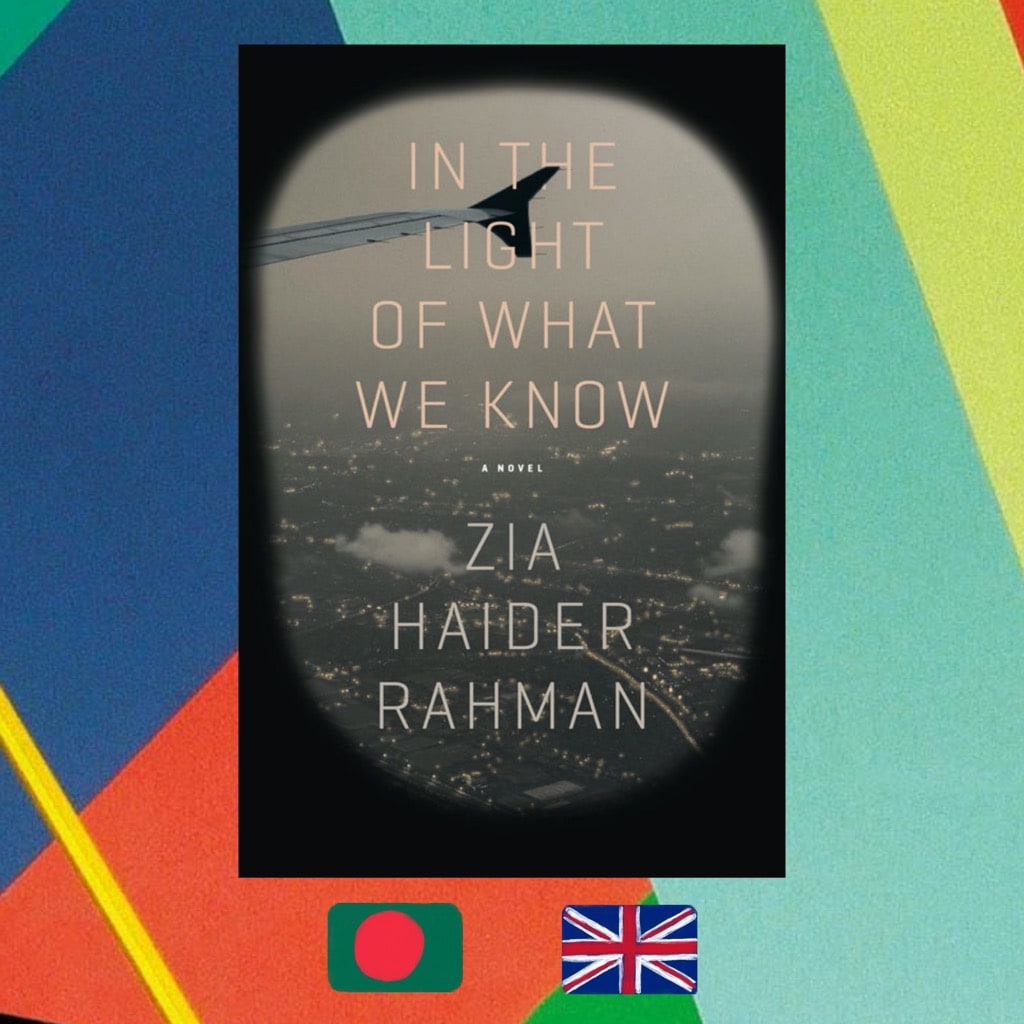

A debut novel about a man trying to find acceptance despite the class and race separations is dense with thoughts and revelations, steeped in ice-cold loneliness—an outsider’s usual bedfellow

FROM BANGLADESH and UNITED KINGDOM

WHAT IT’S ABOUT: The unnamed narrator is a mortgage securities banker who may not be in his job much longer, as the novel begins in fall 2008. Raised in privilege, he is a British Pakistani man but doesn’t face the same level of othering as his British Bangladeshi Oxford classmate Zafar from a working-class background. Zafar appears on the narrator’s doorstep out of the blue, disheveled and strange, and begins to recount the events that transpired in his life since their last meeting. The narrative includes the narrator’s memories of their friendship, as well as Zafar’s confession, that the narrator reconstructs using the voice recordings and notebooks of his friend. The two accounts unfold into a collection of ideas, thoughts, as well as Zafar’s impossible romance with Emily Hampton-Wyvern, a woman from the British aristocracy, which becomes a metaphor for his alienation, as well as a devastating culmination in Zafar’s disintegration.

WHO MADE IT: Zia Hader Rahman was born in rural Bangladesh, but his family moved to the UK during the Liberation war. Growing up in poverty unimaginable for Britain, Rahman got his big break when he was accepted to Oxford to study mathematics. Further scholarships led him to Cambridge, Yale, then to a stint as a derivatives trader at Goldman Sachs. Rahman then got a law degree and worked as a human rights lawyer, as well as engaged in anticorruption activism, before he made his fiction debut with “In the Light of What We Know.” He was a Radcliffe Fellow at Harvard and taught at various universities. Currently, Rahman is working on his second novel, “Creation.”

WHY DO WE CARE: This is a novel about belonging. Belonging, just like the pursuit of otherness, is one of the central themes of any liminal experience, as well as any cultural narrative with which Supamodu concerns itself. But belonging is also a beast of many claws and peculiarities. Everyone who belongs is alike; everyone who doesn’t belong feels alienated in their own way. Rahman gets at the intersectionality of an East Asian man’s struggle in Britain from the get-go, as he establishes the differences between Zafar and the narrator, which are more subtle and deep-rooted than just the presence of money. Rahman’s not exactly inclusive in this pursuit, as, for instance, the women in the narrative, from the poorest Bangladeshi to a conservative British matriarch, are merely metaphors that punctuate Zafar’s existence. At least one white American female critic has accused Rahman of misogyny, a dead-easy take on the subject. But the same omission in the novel applies to people of varying classes, too, with the privileged getting more traction because they are in positions to reject Zafar, while the impoverished ones are an area of inaccessibility, for which Zafar himself is too privileged in his current iteration. Despite the staggering length of the novel and the number of countries traveled by the protagonist, “In the Light of What We Know” is an agonizingly insular book, where everything centers around Zafar’s internal struggle. In his quest for belonging, he manages to score all the material markers of integration but remains lonely. He doesn’t truly get closer to anyone in his new stratum, and only further loses touch with his family, where he was always the odd one, and his previous stratum, such as the two British construction workers with whom Zafar shares a brief job and affinity elevated above racial separation. Beneath all the layers, “In the Light of What We Know” is about loneliness. Inseparable from the quest to belong, it’s also the price one pays for passing the threshold, and like any deprivation, it can lead to madness.

WHY YOU NEED TO READ: “In the Light of What We Know” is full of markers of Western acceptance. Oxbridge, Ivies, Wall street, suits, dinners, pointless small talk, international diplomacy, and the acquaintances it brings. Zafar collects them, as if they were pokemons, burrowing into the neolib core, and the narrative accumulates his achievements along with the plump collections of quotes from the world’s most significant thinkers as if it was all a dossier, an application to be considered Occidental. But the man, who is utterly lost, and angry, violent even, beneath all this weight, only comes alive when he’s on the subject of math. Math, devoid of humanities’ hubris, belongs to no one, and Zafar finds solace in its splendors. But it doesn’t sustain. If you care to be of the world, a more broad intellectualism is demanded. And what’s intellectualism, if not another invention of the wealthy that allows for further separation of the classes, and comprises a useful tool of manipulation? Boris Johnson reciting the Iliad for kudos, or a man of color trying to dissect an empire after the colonies through an encyclopedic effort of defiance, are adjacent occurrences. But the patting on the back, that transpires in both cases has vastly different consequences. An inflated white fool is trusted with the country’s future, while the brilliant man of color is assumed to be a margin of error, and never entirely accepted. The excruciating essence of the novel is that throughout all of the experiences, acquiring all the knowledge, and growing exponentially, Zafar, who seemed so full of promise and potential on the surface, had always been alone and miserable. No one fares well in emotional austerity, but least of all, men, who are conditioned to know: the world will be theirs if they only follow the rules. However, when they do, and the world still resists, havoc is wrought. Initially published in 2014, “In the Light of What We Know” holds its sway in the Brexit era, as a perfect indictment of Great Britain. But it is also a universally relevant novel that denotes: there will be no dismantling of racism without the fall of empires, capitalism, and patriarchy—and vice versa.

Zia Haider Rahman, In the Light of What We Know

Published by Picador in 2014

For more content like this sign up for our weekly newsletter