A coming-of-age story set in a Krahô people reservation shows the double bind of alienation that an indigenous young man has to grapple with as he becomes the man of the house

FROM KRAHÔ PEOPLE, GÊ PEOPLE, BRAZIL and PORTUGAL

WHAT IT’S ABOUT: At just 15, the indigenous Krahô man Ihjāc in the North of Brazil is already a parent, a husband, and the leader of his family, as his father had recently passed away. When Ihjāc starts seeing haunting visions of spirits, the collective opinion is that it’s time to throw his father a funerary feast. But Ihjāc suspects that he’s becoming a shaman—a gift that comes with responsibility and a societal stigma in the tightly-knit community. As Ihjāc tries to rid himself of the life-altering affliction by seeking modern medical help in the nearest city, his journey becomes a rumspringa of sorts, an attempt to find himself in the world where impenetrable structures surround him. But is there a way out?

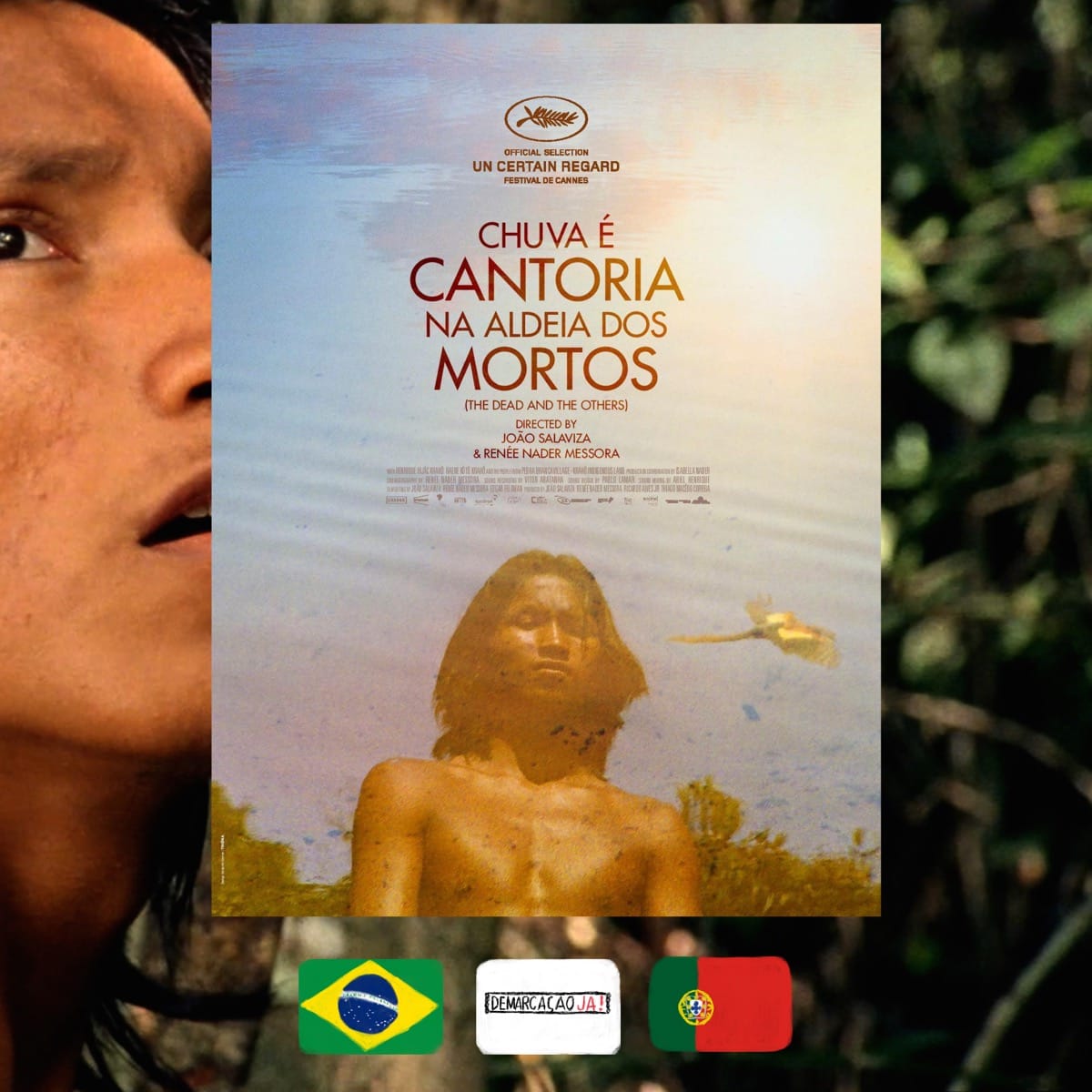

WHO MADE IT: Brazilian Renée Nader Messora and Portuguese João Salaviza are a duo of filmmakers and a real-life couple. Salaviza has a more extensive filmography, with a good eight shorts under his belt when he made his feature debut with “Montanha,” another coming-of-age story but set in the city. It also became his first collaboration with Messora, then an assistant director. Then came “Russa,” where Messora served as the cinematographer, narrowly followed by “The Dead and the Others,” where Messora was, once again, in charge of photography, and the two shared the responsibilities of writing, directing and production.

To make the film, Salaviza and Messora moved to Pedra Branca, a traditional Kraho village in the province of Tocantins, and worked with the locals closely to create the film. Every cast member, all sharing the last name Krahô, plays a fictionalized version of themselves, including Henrique Ihjãc Krahô in the leading role of Ihjãc, in which he shines on the cusp between tenderness and maturity.

WHY DO WE CARE: Rooted in anthropological inquiry, “Dead and the Others” is a work of ethnofiction in the finest traditions of Jean Rouch and Pedro Costa. However, it’s also one of the few such attempts made in the Amazon, where anthropologists usually prefer to draw their own cinematographic conclusions rather than engage the locals in the narrative. The story is both universally recognizable and tailored to the space and the culture. The narrative makes all the necessary turns to shed light on how existence within the particular Kraho society and the indigenous Brazilian communities at large, is different or similar to that of the viewer. Particular emphasis is placed on the generational experiences and encounters, such as the trauma of colonization that keeps reverberating through the many invasive interactions that the indigenous dwellers of Pedra Branca keep having with the settler state.

Even though it’s strikingly beautiful, from the village’s lush landscapes to Ihjāc’s face taught with disaffection, the film’s sheer power lies in its audible content. The voices that come to Ihjāc through the Amazonian thicket and the very particular monotone of the Krahô language all come together in a soundscape that’s enveloping, otherworldly, and yet familiar on some visceral level.

WHY YOU NEED TO WATCH: Coming of age stories, when well done, are always tender, tense explorations of what it is to find yourself in the world. In “The Dead and the Others,” the adolescence is fused with maturity, since with his social roles, Ihjāc doesn’t have a choice whether to become a grown-up or not. But more than that, they are informed by an additional layer, a parallel reality, where the macaw beckons Ihjāc, urging him to start walking the line between worlds as a shaman. The thresholds abound, with another one of them a long stretch of land between the city and the village, which even when conquered by car, remains impenetrable, the glass dome within reach, but it remains hard to say which side Ihjāc is on, and he doesn’t know either.

The scene in which fatigued Ihjāc, who can’t go back home yet but also isn’t allowed to stay, is singing along to a pop song, is reminiscent of the dance scene from Claire Denis’ “Beau Travail,” Denis Lavant twirling in the lights, as his life as he knew it flees. The actual ending in “The Dead and the Others” is just as melodic, but filled with a darker truth, that seeps into reality, where Ihjāc’s and Indigenous existence in Brazil is growing further endangered every day, as the threats abound, and capitalism and colonialism are closing the noose. Crisis of faith and crisis of identity come together in a space that’s far away from the ideological belonging we’re formally used to. Yet, the obstacles to fulfillment are reiterated and matched, as stigma and expectation add rocks to the pockets.

A careful, quietly roaring narrative, “The Dead and the Others,” demands patience. But it also offers an unparalleled opportunity to submerge oneself into the culture that we otherwise get very little insight into and experience it not through a museum glass, but a warm-blooded existence of a young person. It is a refreshing take on the forever current, but too often trivialized coming-of-age genre, crafted in a considerate, heartrending, and poetic manner. Thought-provoking and imagination-stirring, “The Dead and the Others,” one of those films that live within you long after the screen has gone dark.

The Dead and the Others (Chuva É Cantoria Na Aldeia Dos Mortos), 2018

Directors: João Salaviza & Renée Nader Messora

For more content like this sign up for our weekly newsletter

WATCH THE TRAILER