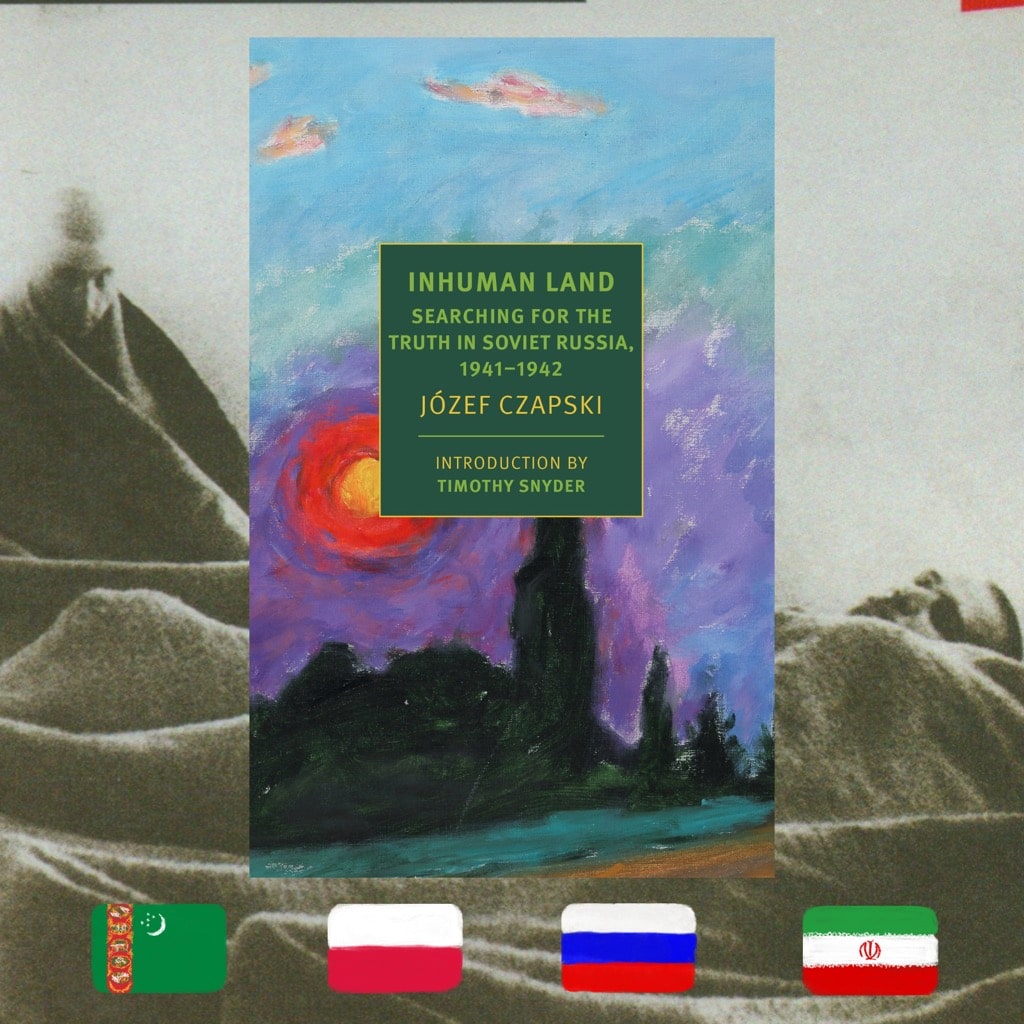

The memoirs of an artist and activist who traveled across USSR in search of Polish POWs during WWII, that give an unflinching account of life in the remote corners of the Soviet empire

Józef Czapski was a Polish artist, writer, critic, and activist who soon after the start of World War II found himself a prisoner of war in Russia. However, as a treaty was signed between the Soviet Union and Poland, Czapski and other Polish POVs were released. Czapski was tasked with the job of investigating the fates of his compatriots who were captured, tortured, and often disappeared by the NKVD. Already familiar with the country, Czapski was repeating the missions he had previously carried out to locate the missing Poles captured by the Bolsheviks.

Throughout his arduous journeys across Russia, as well as Ukraine, Turkmenistan, Iran and, his ultimate destination, Iraq, Chapski kept a meticulous account of everything that was happening to him and the people around him. One of a series of books written by Czapski about the Soviet Union, “Inhuman land” presents a priceless witness account of what was happening in Stalin’s Russia behind the curtain of the war against Germany. It portrays the way the empire-building of the socialist state neglected the “social” element by creating generations of miserable, forgotten people in the remote corners of its vast space.

“Inhuman land” is hard to read, and this is for two different reasons. First, as a witness account, it is painstakingly thorough, so sometimes you get bogged down with all the details. Undoubtedly necessary to present a full picture, these details are overwhelming, and demand a patient, careful reader. Second, even though this WWII book has barely any mention of the period’s usual horrors, such as Nazi concentration camps, it is deeply disturbing. The brutality that happens on pretty much every single page of this book is both institutional, fostered by the Soviet system, and sporadic, born of poverty, dissatisfaction, and other random factors.

And then, outside of the human factors, there are the many plagues of wartime. The desolate landscape that Czapski travels, with colors entering the picture only when he arrives in Turkmenistan, is ravaged at every step by hunger, illness, and desperation. Czapski often resorts to comparing the USSR he encounters with the USSR fresh after the Civil war that he experienced earlier. His observations are revelatory, practically unmatched by anyone else. So rarely did the people with Czapski’s level of mastery of language get access to the Soviet masses left behind in the strive for Soviet grandeur.

But despite the very bleak setting, “Inhuman land” is also a very humbling, hope-inspiring book. Now and then glimmers of beauty emerge from the misery, like a kind gesture, or an extra effort made by someone who cares to make the others feel welcome. And when the surroundings don’t provide respite, Czapski himself becomes its source. He tirelessly tries to fill spaces with poetry, music, creativity, helping people survive by knowing there’s more to life than war. And his spirit is especially striking when he crosses paths with the Russian writer Alexei Tolstoy. Although not an active enforcer of the regime, Tolstoy is comfortably sheltered by it. And the disparity between the two men of words is striking: the well-fed Tolstoy perceives poetry as a connoisseur, with gesturing and reasoning, while Czapski merely lives it.

Which brings to the realization that the survival of the narrator throughout the book is miraculous. Aside from the dangers of coming close to the Soviet regime, the hunger, and the illnesses, there is a very particular ghost that hangs over the text. Or, rather, around 22,000 ghosts. Czapski himself often mentions them and retrospectively it appears hard to omit the Polish Nationals who were executed by the NKVD in the Katyn massacre of 1940. Many of the people that Czapski was after laid buried in the mass graves near the Katyn forest as he tirelessly sought them throughout the book’s events. And even when he first published the book, in 1949, the subject of the Katyn massacre was still under veto in Poland. (The Russian government publicly apologized for it only in 2010).

There is so much poetry in this parallel the book has with this lesser-known WWII tragedy. The search in vain for people who can not be found that propels Czapski on a relentless journey of witnessing is a devastating yet very human coincidence. In a world where justice is a fleeting concept, at least the poetic kind of it is achievable. “Inhuman land” is an essential account of things few others had been able to tell. It’s also definitely one of those books that testify to the ability of literature to take stock of things that are too vague or too horrible.

Józef Czapski, Inhuman Land: Searching for the truth in Soviet Russia, 1941-1942 (Na nieludzkiej ziemi)

Translated by Antonia Lloyd-Jones

Published by NYRB Classics in 2018

For more content like this sign up for our weekly newsletter