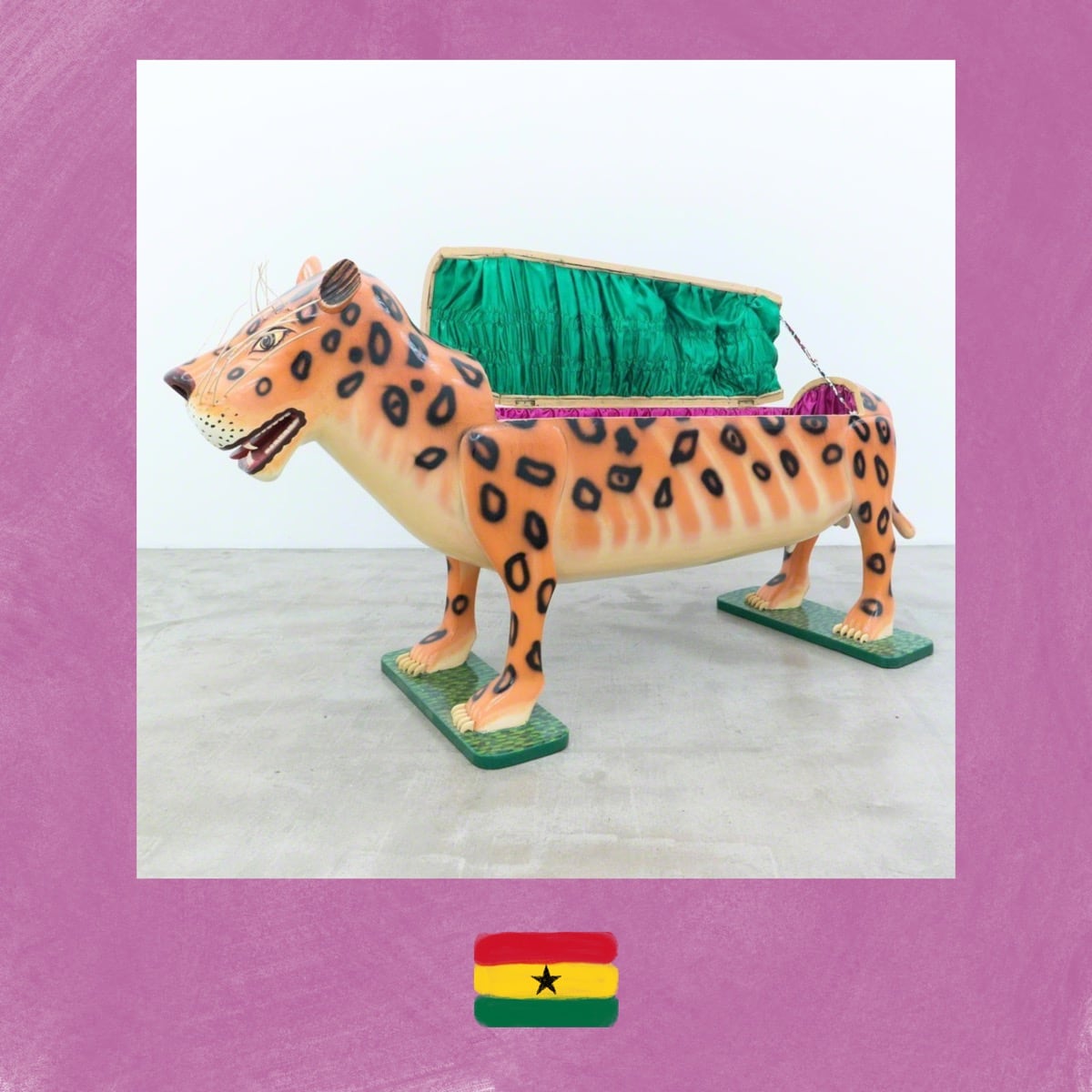

Rooted in the tradition of his Ga people, Paa Joe’s coffins are whimsical, yet concise impressions of their owners—and a staggering reimagining of what art and death really mean to us

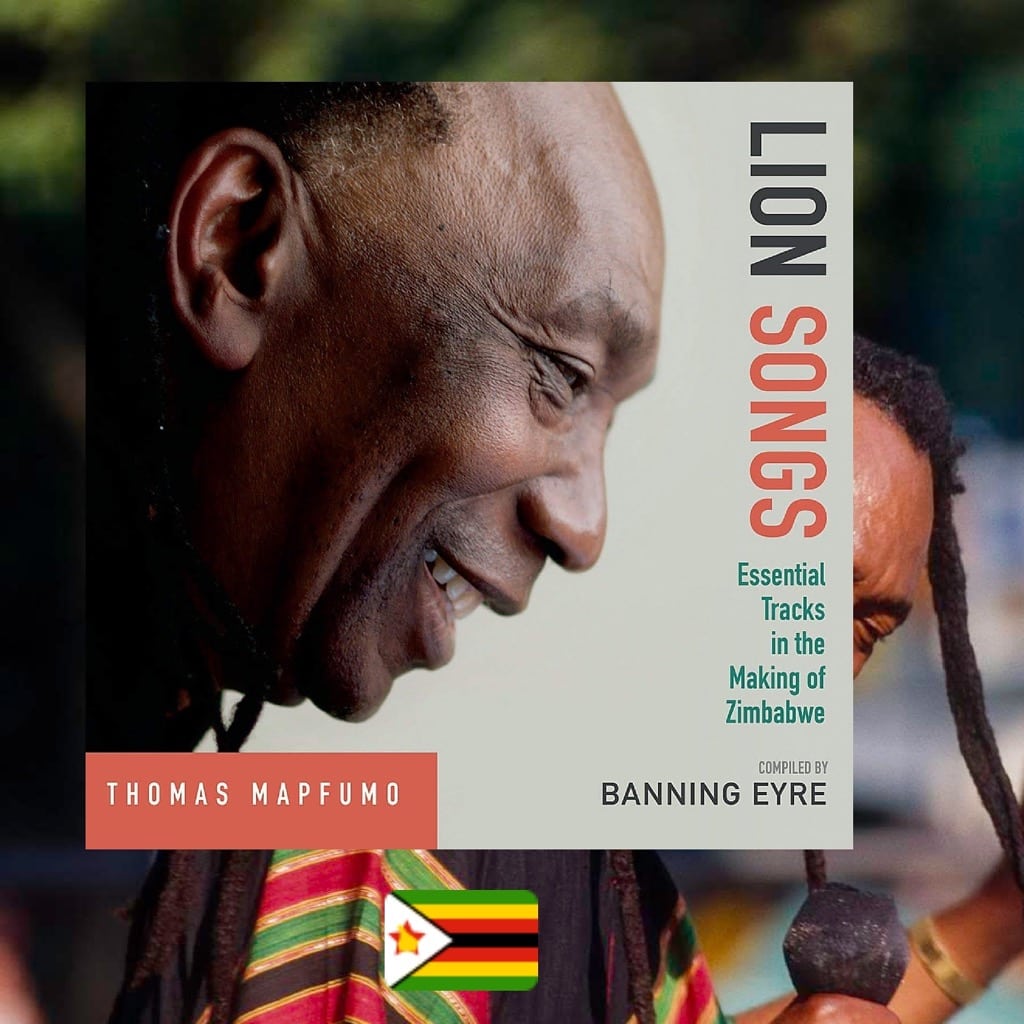

FROM GHANA and GA-ADANGBE PEOPLE

WHAT’S GOING ON: Elaborate sculptures of animals, plants, and material possession are crafted from wood and covered in bright veneers. The fauna is represented by jungle and domestic animals, birds, various reptiles, and sea creatures. Fruits, vegetables and cocoa pods cover flora. Everyday objects recreated with artistry and imagination include iconic drinks, like the Ghanaian lager Star and Coca-Cola, staple foods, various electronic devices, transport vehicles, musical instruments, and many different shoes, from Air Jordans to high-heeled pumps. However, the caveat is that these are not simple sculptures: they are coffins made by the famed Ghanaian coffin sculptor Paa Joe, and they’re meant to carry the deceased individual’s identity and vocation to the afterlife. Not the first in a long line of Ga coffin makers, Paa Joe, has become the best-known master of fantasy coffins in the world.

WHO MADE IT: Joseph Tetteh Ashong, best known as Paa Joe, has been making coffins since he was a teenager. His mentor, carpenter Seth Kane Kwei is widely considered the inventor of fantasy coffins when he modernized the tradition of his people, the Ga-Adangbe, to bury chiefs in figurative coffins, and made it widely accessible to mere mortals. After training under Kwei for 12 years, Paa Joe established his own business, where he began crafting his own elaborate creations and teaching prospective coffin makers. Initially established in Nungua, currently, Paa Joe runs his studio in Pobiman along with his son Jacob and masters Tawiah and Ben, whom he’d previously trained. Although many newer workshops have popped across the country as demand for fancy funerals doesn’t wane, Paa Joe remains the best-known coffin maker outside of Ghana and its funeral industry. He has toured the world with exhibitions, and his works are in the collections of various museums worldwide, including the British Museum.

WHY DO WE CARE: The business of death remains to be one that’s diverse and peculiar, both taboo and reflective of society’s trends, and always subject to much discussion. For instance, the first part of 2020 can be perfectly summed up in two internment practices that have caused much commotion from the general public and often polarized society. First were the funerals of victims of COVID-19 across the world, often without loved ones in attendance, streamed online, and even conducted in ways that evoke mass burials. The second was George Floyd’s golden coffin, which became an eloquent symbol of something akin to reparations—or a reason for racist contention, because, of course, even a dead man’s coffin is put under scrutiny.

Meanwhile, the Ghanaian funeral practices have been holding the world in awe for a while now. The country’s dancing pallbearers have been one of the most delightful yet morbid memes on the internet lately, with action figures created in their likeness and the viral video of their routine often shared as a warning against careless behavior in the times of COVID-19.

Paa Joe and his coffins have also gotten quite a lot of press because of their unexpectedly whimsical approach to departures from the earthly realm. But now more than ever, they deserve some attention: after all, the year 2020 is the year when we look death in the eye in many ways, and we need more to ground the subject of dying in cultural and creative contexts.

WHY YOU NEED TO PAY ATTENTION: Paa Joe is the ultimate artist whose voice to uplift if you want to assess the “Black Lives Matter” movement in a meaningful way. Not only is he a fascinating black creator and a whole institution whose legacy has gone far and wide, but Paa Joe is also working in deep connection to the culture of his homeland Ghana and his people. The Ga-Adangbe are endemic to Ghana and Togo but mostly reside in the Greater Accra region of Ghana. Ga people were among the predominant ethnic groups to be abducted into slavery in the earlier stages, along with Aja, Fon and Ewe—before Yoruba became the primary target.

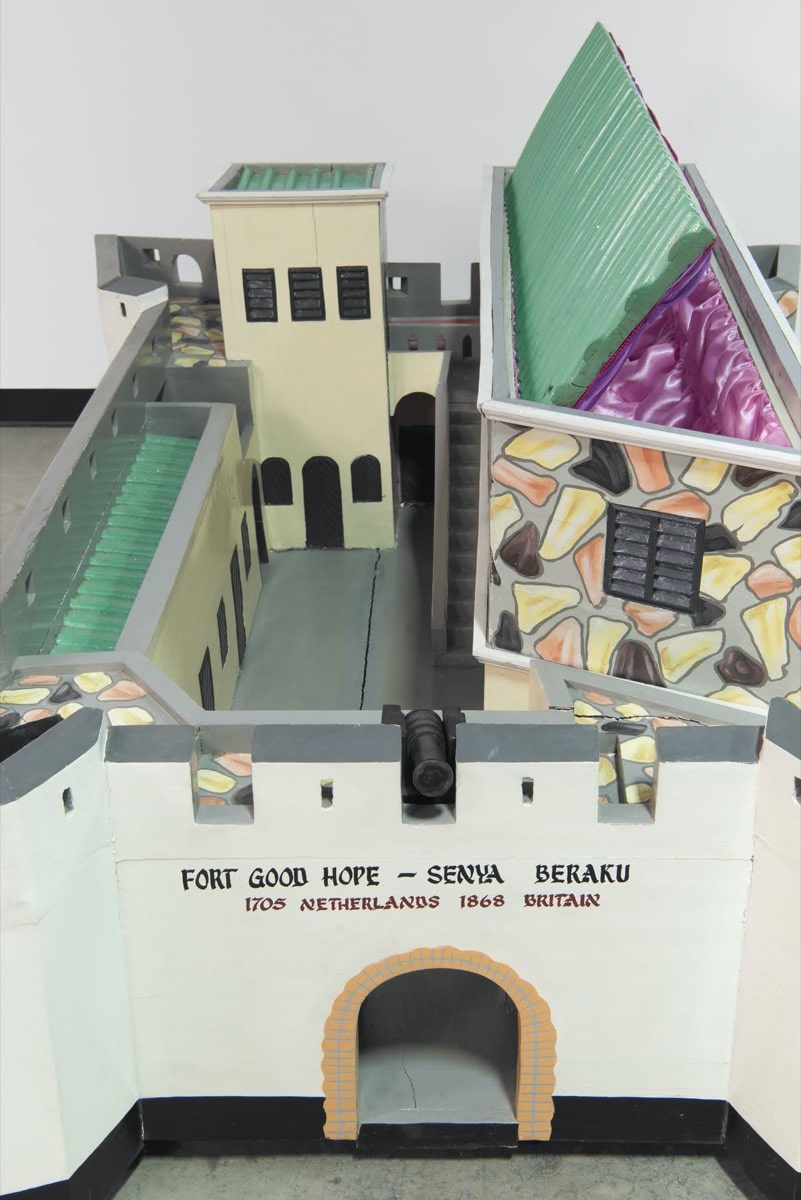

In Ghana, one can still find the so-called “slave castles,” European-built trading posts used as stop-over stations for slave traders. For many of the six million Africans abducted into slavery, these forts became the last semblance of their home continent before they perished on their journey through the Middle Passage, or endured a lifetime of bondage in the Americas. No visit to Ghana goes without observing those haunting, starkly white buildings that remain somber monuments to one of history’s worst atrocities. One of Paa Joe’s lesser-known projects, which had been on display at his solo exhibition at the American Folk Art Museum and others are models of 13 slave castles reinterpreted the same way as his coffins (only seven were displayed). But they’re not final receptacles, as no one would ever aspire to be buried in a slave castle model for fear of attracting bondage into the afterlife.

For someone who doesn’t know their history, these elaborately detailed sculptures might seem whimsical. But in their essence, juxtaposed to Paa Joe’s coffins, they take on an eery air, showing just how flawed human life and history are, and how flawed their material cultures. Something so grand and solemn as these castles has the tragic, impossible history of captivity. Meanwhile, a humble cocoa pod or a red-tinted snapper can become symbols of prosperity and liberation. This reversal of the capitalist values speaks to the current moment where statues of men considered great are wrangled off their pedestals, and the emphasis is put on how people are allowed to leave the earthly realm.

And this is what makes Paa Joe such a complex and important artist. His understanding of his art’s purpose is crystal clear, yet remains deep and tangled in the Ga understanding of the influence that the departed can have upon the living. The reverence, joy, and appreciation for honest labor that go into the Ga funerals are reflected in the fierce, delightful, and elegant simplicity of Paa Joe’s coffins. An artisan who pours more of his soul into his creations than many contemporary artists do into their less functional work, Paa Joe is one of Ghana’s leading artists for a reason. His works are too meaningful to merely be displayed or absorbed into the vortex of the art markets, and yet they last far beyond the scope of their owners’ lives. Art that serves in life and death, and welcomes decay as part of its built-in practice of transcending material limitations of our reality: impressive and quite unmatched.

For more content like this sign up for our weekly newsletter

MORE PAA JOE