Frank Walter spent his life creating a vibrant body of work that reimagined the existing social order. Posthumously, his art is a revitalizing deconstruction of race, history and the universe

FROM ANTIGUA and BARBUDA

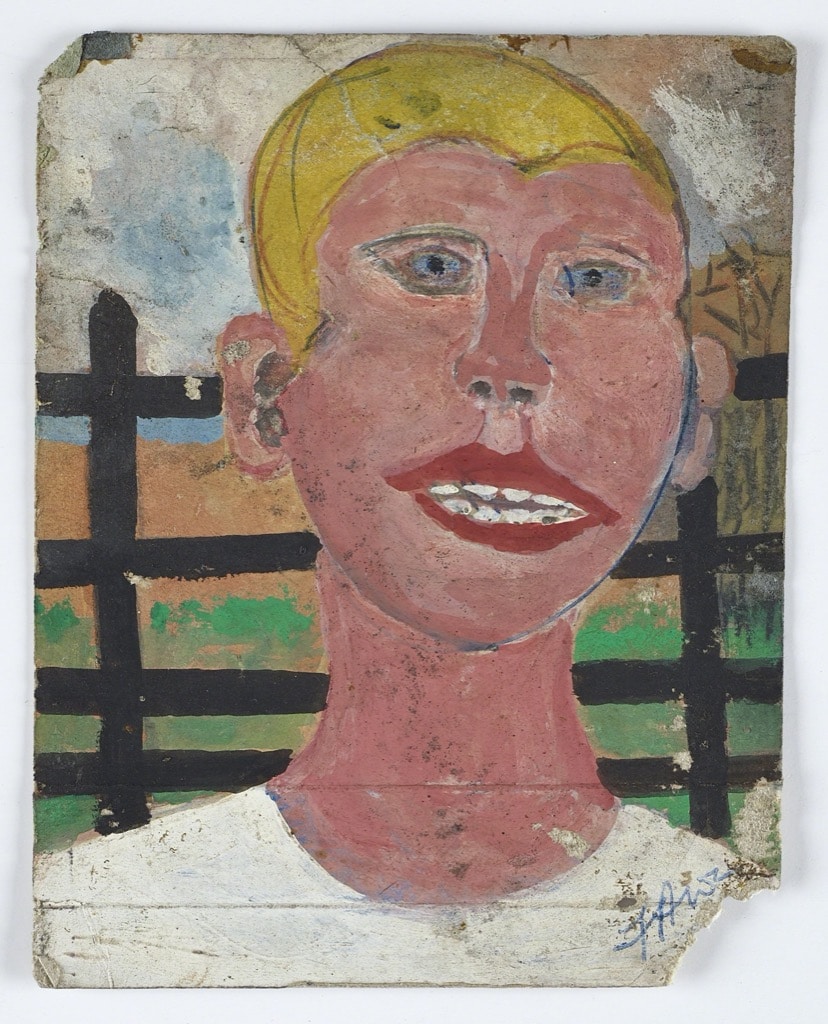

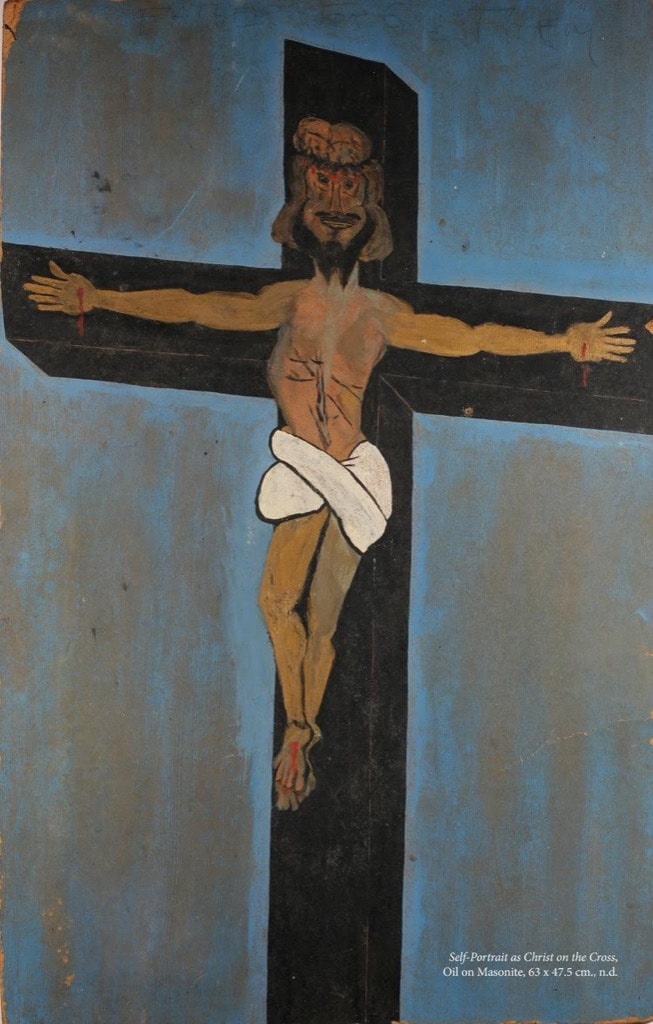

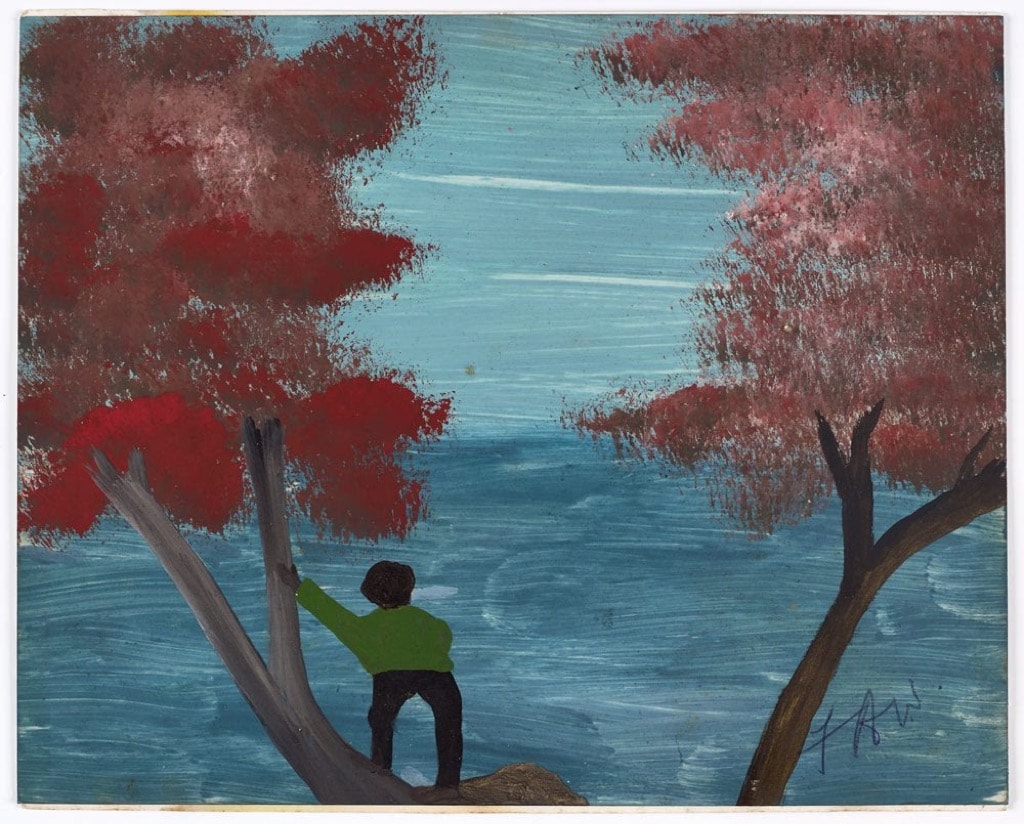

WHAT’S GOING ON: In 2009, the Antiguan intellectual and eccentric, prime minister candidate and recluse for the last 25 years of his life, Frank Walter died in his self-built home overlooking Falmouth harbor, where no water, electricity or unwanted humans ever reached him. He left behind a vast estate of just under 10 thousand artworks, at least 1.5K of them right in his home, as well as thousands of written pages on various subjects and days worth of audio recordings. This expansive collection of one inquisitive, ingenious, and tireless mind’s fruits, which consists of paintings, wooden carvings, and photographs, became a sensation in the art world. It made the creator a revered figure of Caribbean art posthumously and was celebrated at Antigua & Barbuda’s Pavillion at the 2017 Venice Biennale. Walter’s artworks were made mostly with the use of found objects, whether it was hand-harvested wood, pieces of paper packaging, or varied scraps and bits that he endlessly sought to upcycle. They are striking, full of foreboding beauty and primal energy, created with the enthusiasm of a self-taught artist, but indicating an academic level of the methodology behind them. A man of many interests, concerns and exploits, Walter allowed various themes into his work: from the landscapes and sunrises physically surrounding him to the abstract musings on the world’s cosmology and energy, to surreal renderings of the world events, where he placed Hitler on a cricket field and reimagined Princess Diana and Prince Charles as Adam and Eve. A sweeping, extensive heritage, and a lifetime of failed attempts to find acceptance in the art world, have made Walter into a posthumous rebel icon and garnered him praise as a Leonardo da Vinci-kind of an omnipotent artist.

WHO MADE IT: Despite being born in a black Antiguan family of modest means, Frank Walter had a concrete belief that his ancestry, with a slave-owning grandfather here or there, linked him to European nobility. In his twenties, Walter became the first sugar plantation manager of color on the whole island and one of the first black Antiguans to wark on the same terms as whites. He was so successful that he almost became a sugar executive, but Europe was beckoning, and Walter left for a decade of travels around the continent. However, he was bitterly disappointed by what he experienced as a black man in the old world, where the possibilities available to him were limited to menial labor. As racism and poverty ate away as his sanity—he was placed in a “nerve hospital” at one point—Walter managed to make the most of his time abroad by studying in the European libraries, making extensive research of his genealogy. When Walter finally returned to Antigua, the sugar economy was in shambles, and there were no career prospects in this once-flourishing industry. Walter moved to Dominica and succeeded in receiving a grant from its government to develop a plot of land he named Mount Olympus. Walter took to cleaning the estate to prepare for planting, while also experimenting with clean sources of energy and his art practice. However, once the estate was ready, the government took it back to use in a corrupt scheme. Once again, severely disaffected, Walter again returned to Antigua. In the late 1960s, he decided to try himself out in politics but was defeated by Vere Bird, who went on to stay in power on and off until the mid-90s. The defeat became a final blow to Walter’s desire to participate in social life. He built a house and studio and lived out the remainder of his life in isolation while working on his art and theoretical writings, and making money by selling souvenirs in a small shop.

WHY DO WE CARE: Some artists pick one thing, a medium, a subject, or a means to express their artistic manifesto, and stick to it throughout their careers. Such tenacity inspires awe, and the style is always recognizable. But there is nothing that I personally like more than an artist who creates a whole new universe with their artwork or offers a new taxonomy of the existing world through their renderings of it. Frank Walter engaged in both of these practices, while widening the limits of the possible, and also reinterpreting the things around him. And those interpretations, it seems, were too easily brushed away as convictions of a disturbed mind, as his repeated attempts to find ways to exhibit his works never bore fruit. But they are, in fact, gems challenging the very fabric of reality which we inhabit, defiant stabs at the status quo from a man who had been hurt too often by assumptions made about him by a non-meticulous onlooker. At some points in life, Walter worked as a sign painter and as a studio photographer, which became meaningful creative undercurrents for his work and informed it with a very accessible, beguiling aesthetic. Yet it’s the curiosity, the ideological fervor that drove Walter to contextualize his work so brilliantly.

WHY YOU NEED TO PAY ATTENTION: Neither an abstract artist, nor a realist, Frank Walter painted not what he knew to be true, nor what he saw as impossible. Instead, he offered a look at the universe through a prism of aspirational reasoning. And whether the subjects of his many artworks are reclaiming the narratives of life for the betterment of humankind, or seeking to fix the injustices with which Walter himself grappled, they show the sheer genius beside them. His was a mind that could connect the dots and see the world as a series of interlinked subjects. Walter’s personal history reflects the odds and ebbs of affirmation that a man of color could experience through the past century: from benefiting from Antigua’s labor rehaul to break the glass ceiling, to being driven to severe depression by the many alienations, such as his beloved, a white-passing Antiguan woman, leaving him upon arrival to Europe, or lack of any acknowledgment of his heritage. The crack in the man started appearing when he saw that the world wasn’t what he’d hope it would be, something that can be compared to the discontent of a parent of an irreversibly troubled child. And so Walter stayed away from humanity and reconciled the injustices through art. For instance, even though his claim at aristocracy was never accepted, he crowned himself with the delightful title of 7th Prince of the West Indies, Lord of Follies, and the Ding-a-Ding Nook. Whether he was convinced in his white aristocratic lineage in earnest, or if it was a part of his profoundly imaginative outlook on life doesn’t even matter. His approach, while wildly fascinating, also served to dismantle the social constructs of class, race, and ancestry, showing that belonging or not sometimes boils down to willingness, while humans construct the surrounding borders. It’s both heartbreaking and illuminating to see his self-portraits where he presents himself as white because that, to him, was a goal: in one of his writings, he referenced finally being able to be white. But it’s also an unobstructed look at a world where a human being is not held back by binaries and borders. Appreciating Frank Walter’s work is essential today because it provides guidelines for what our society could be if humanity collectively had just a little bit more imagination.

For more content like this sign up for our weekly newsletter

MORE FRANK WALTER