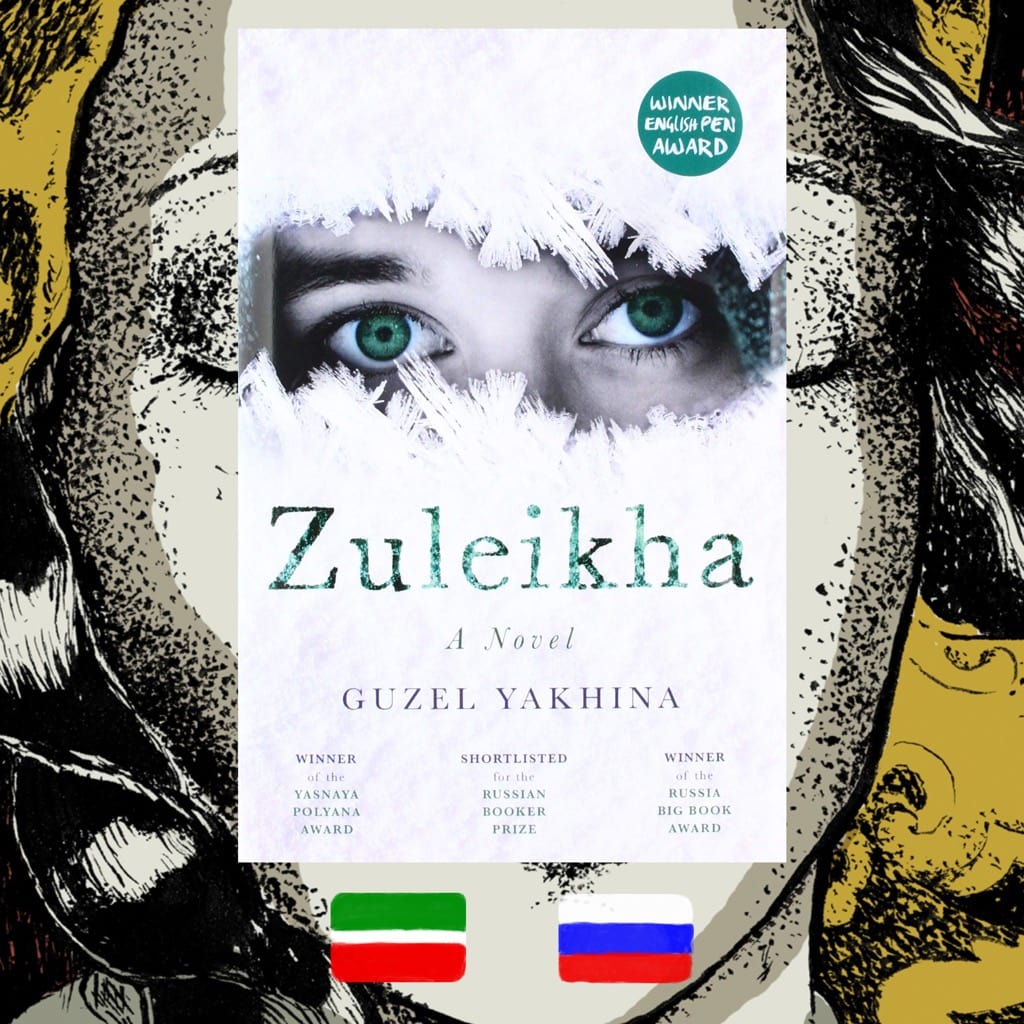

A forceful, award-winning and debate-sparking debut novel about life in Gulag through the eyes of a diverse cast of characters, with fierce but timid Tatar woman at the forefront

WHAT IT’S ABOUT: In the year 1930, peasant woman Zuleikha lives in a remote Tatar village with her abusive husband Murtaza and his controlling ancient mother that Zuleikha secretly calls “Vampire Hag.” Zuleikha never delivered a male heir, and her four daughters died in infancy, which makes the tiny submissive woman an easy target for the whole family. In the aftermath of the 1920s hunger, they’re barely getting by through backbreaking labor, yet when dekulakization reaches their village, Murtaza is targeted as “prosperous.” When he resists and is murdered by a promising Cheka official Ignatov, the family’s property is taken away along with Vampire Hag, and Zuleikha is put on a prisoner train to Siberia. The long, perilous journey alongside political prisoners from across the USSR, bitter cold, starvation, and Gulag labor upon arrival become her new reality. The novel follows Zuleikha, her fellow prisoners, and Ignatov, who is charged with building the labor camp, over the next two decades, as suffering, the need for survival, humanity, and the labor village of Semruk tie the destinies of strangers into an inseparable bond. In a strange turn of events, captivity brings Zuleikha agency and offers a chance to start anew as a woman and person. She discovers that human connection, love, and even motherhood are still possible for her, despite the haunting of her past life’s ghosts.

WHO MADE IT: Guzel Yakhina is a bilingual Tatar-Russian writer, who grew up in Kazan, but has resided in Moscow for the past twenty years. A graduate of Moscow Cinema School’s screenwriting program, she made her fiction debut with Russian-language “Zuleikha” in 2015, and has since penned another novel, “My Children.” The idea for “Zuleikha,” which brought Yakhina prestigious awards in Russia, was sparked by the stories Yakhina heard from her grandmother, who lived in a labor camp as a child during Stalin’s rule. Th, the fictional village of Semruk, is loosely based on that camp deep in Krasnoyarsk Krai, while the events of the novel are based on memoirs of various Gulag prisoners that Yakhina researched during her writing. American Lisa C. Hayden is Oneworld Publications’ trusty translator from Russian, responsible for their whole Russian fiction catalog, including the much-lauded “Laurus” by Eugene Vodolazkin, for which she received numerous awards. She has also translated Russian books for other publishing houses, as well as short fiction by Platonov and Prishvin.

WHY DO WE CARE: In “Zuleikha,” Guzel Yakhina presents a masterclass in showing macro events through a micro vision. The novel starts with the line “Zuleikha opens her eyes,” which also happens to be the original title in Russian, and follows the protagonist closely, through the very physical experiences in her loveless home. And even though after Zuleikha’s departure for Siberia, the point of view shifts to grant interiority to other characters, too, the intimacy between Zuleikha and the reader persists throughout and allows a unique insight into a woman’s awakening. Novels about Stalin’s purges and Gulags, much like Holocaust fiction, are very rarely uplifting by definition, and in “Zuleikha,” too, there are vast amounts of misery. But as the reader, already versed in Zuleikha’s domestic oppression and traumas of unfulfilled motherhood, prepares to see her sink entirely in the harsh reality of internment, she shocks with a sudden feminist revival. Not alien to suffering, Zuleikha embarks on a quest to find contentment in her hardships. This journey is so fraught with guilt that as a mother, a widow, and a Muslim woman, that Zuleikha seems to be dealing with twice as many burdens as the other prisoners. The novel pulsates with tension, and Yakhina is no stranger to cliffhangers and melodramatic plot twists. In Russia, it was made into a drama series, which is no surprise. But the turns that the plot takes are not merely plot devices, rather the tools effectively showing the multitudes that life can take, while simultaneously playing with reality’s malleability. And it’s precisely because of this, as well as Hayden’s faithful, inventive translation, that the reader can get a multi-faceted, contextualized understanding of some of the defining moments in Soviet history, as well as its postcolonial baggage through an enjoyable narrative that allows for interpretation.

WHY YOU NEED TO READ: In Russia and Tatarstan alike, the novel was fiercely debated. Some Russian critics thought that Yakhina did not demonize the internment enough, others saw her as a Russophobe. Some Tatar cultural figures felt like she was repeating the colonialist tropes about an Asian unsophisticate empowered by the West; others mused that a woman couldn’t have written something with such detailed accounts of medical practice and house construction. And all those clashing opinions mean that we’re dealing with something incredibly potent. There is no way for anyone who isn’t Tatar, or has no experience of Stalin’s camps, to judge the authenticity of experiences described—nor is it necessary, because the novel’s spectacle offers enough distance from reality. But a careful and patient reader will notice that the power of Yakhina’s writing, along with the beautiful yet accessible language, and passionate world-building, lies within her openness to pointing out the complexities and similarities people share, and the contradictions that exist between them, and within each one. Faith, whether it’s in god, the ideals of Stalin’s vision, art, medicine, high society, agriculture, or even cowardice, is tested in all of the characters with unforgiving vigor, as if destiny is laughing at them, through the satirical wit of Yakhina. And as they struggle, make amends and sacrifices, reason with themselves, grapple with guilt, and fail, humanity emerges. Populated by flawed yet consistent characters against striking, elaborately simple locales, “Zuleikha” is a big, bold and fascinating book. It is a pleasure to read both in the Russian original, and in Hayden’s translation that only adds dimensions to the narrative’s entanglements of personhood.

Guzel Yakhina, Zuleikha (Зулейха Открывает Глаза)

Translated by Lisa C. Hayden

Published by Oneworld Publications in 2019

For more content like this sign up for our weekly newsletter