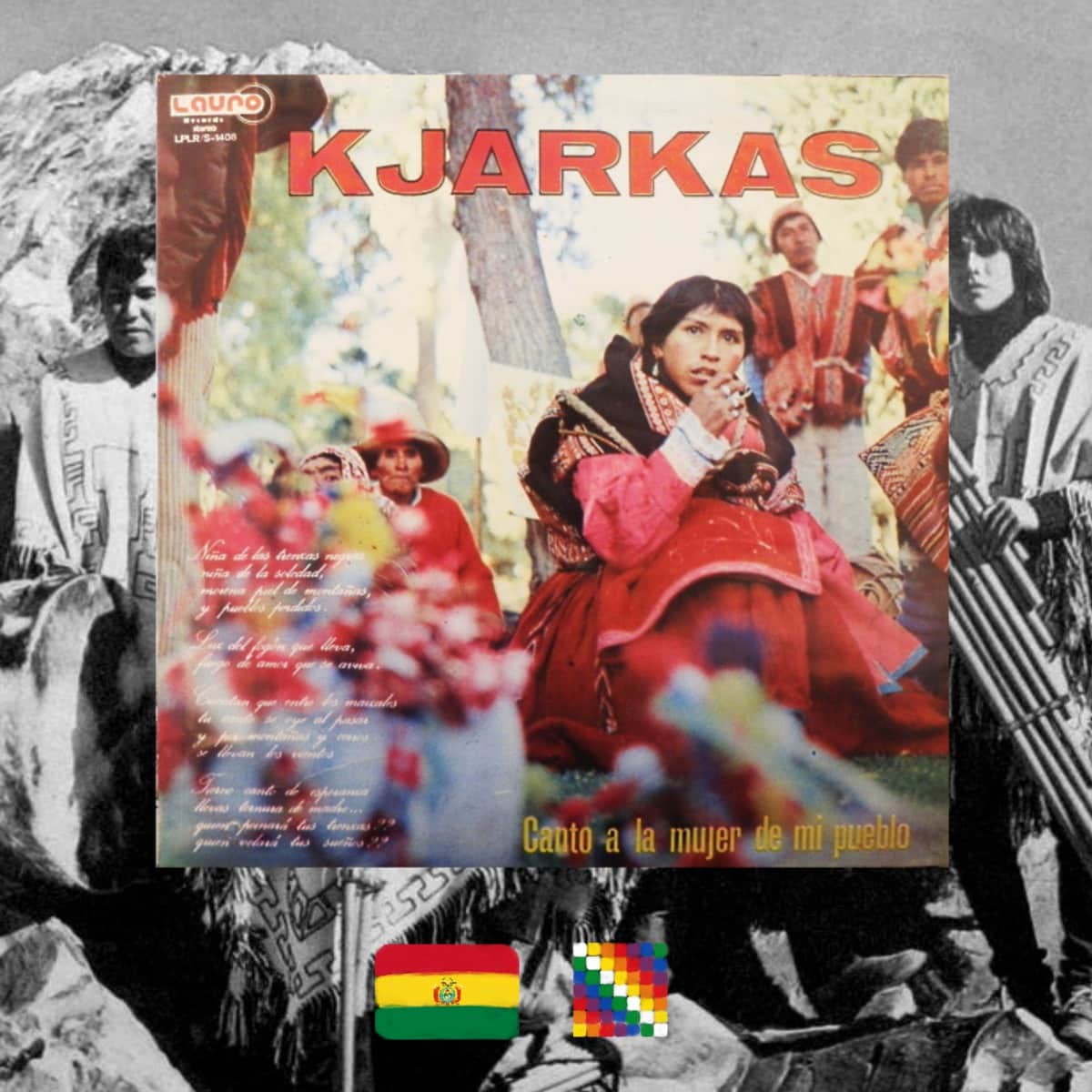

From writing one of the world’s most recognizable dance hits to welcoming the exiled leader Evo Morales back home: the music of Los Kjarkas is the ultimate soundtrack to Bolivian Renaissance

FROM BOLIVIA

WHAT’S GOING ON: If you have a pulse, you must be familiar with the song “Lambada” by the French-Brazilian group Kaoma, where singer Loalwa Braz’s vocals thick as molasses accompany the rhythmical melody that was all the rage in the early 90s discos across the world. And if you missed that decade, you might be more familiar with Jennifer Lopez’s updated version “On the Floor,” which she made alongside Pitbull, and that tore up the dancefloors in the 10s. But it’s quite probable that you will not know the real origins of the song that drips into your ears like molten gold. The original version, “Llorando Se Fue,” belongs to the Bolivian band Los Kjarkas. It’s a much gentler affair, inspired by a traditional Andean melody and set to the Saya rhythm of the Afro-Bolivian slaves. Originally appropriated by Kaoma without authorization, it became the subject of a lawsuit, which Los Kjarkas won, getting their due from “Lambada’s” immense popularity. Today, the legendary band is again in the spotlight, as they made their comeback after not being able to perform for the past year due to threats from the far right that gained prominence after the 2019 coup. And as they release new melodies that manifest the Andean soul of Bolivia, resistant to upheaval and making a powerful comeback, we want to go back to 1981 and see where it all started.

WHAT IT SOUNDS LIKE: Originally, the band got together in the early 70s to perform Argentine zambas, the most popular music style in the country at the time. However, as the wave of Nueva canción swept the Ibero-American region in protest against the oppression of military dictatorships in the 70s-80s, and Bolivia began its gradual return to Indigenous roots and local culture, demand for Bolivian music grew. Los Kjarkas then went through a couple of transformations, finally becoming the band that had later become legendary by turning their attention to the traditional offerings of the rich Quechua and Aymara Indigenous cultures of Bolivia. Adding wind instruments to their voices and guitars was the magical ingredient. The traditional panpipe siku and the flute quena alongside the lute-like strings and tree trunk drums make their music completely unparalleled. It’s folk music, but it also has the decisive force of pop music of the same decade. However, the lack of posturing to fit the changing fashion allows for the whole of Los Kjarkas oeuvre to avoid aging and retain youthful virility and freshness that is unmatched in artificial reimaginings. There are precursors to many subsequent musical trends in their music, including some that seem far fetched, like 8 bit, but that’s the beauty of lucid folk borrowings: the organic material is all there, and there are no limits to how talented people may use them.

WHY DO WE CARE: Bolivia has been the source of exciting news lately, as the almost year-long neoliberal coup in the country had ended, after tireless organizing from the Indigenous communities and the countries workers, with Luis Arce winning the presidential election and the exiled ex-president Evo Morales returning to the country. And in events familiar to those who know about the existence of folk musicians under far-right regimes—for instance, and most famously, Victor Jara tortured and murdered under Chile’s Pinochet—Los Kjarkas had been under much pressure ever since the coup, too. The minority that had been in power for the past year is very staunchly anti-Indigenous in opposition to Evo Morales’s Indigenous-centered politics. There had been many causes for concern, including numerous Indigenous casualties in the coup and ensuing violence. Besides, the right-wing interim government has had a long gripe with the band itself. After all, Los Kjarkas are part and parcel to making sure that Bolivian Andean identity is not erased in favor of the colonizing presence, and they had never shied away from staunchly supporting Evo Morales and his politics. One magazine cover dedicated to Morales’s flight from Bolivia carried the headline with the Los Kjarkas song title “Llorando Se Fue,” which translates as “crying he is gone,” and the band and the exiled leader had been blacklisted throughout the tumultuous period. However, as Morales finally returned to his homeland and his people, Los Kjarkas, too, were finally able to perform in Bolivia as well, with an appearance at the rally in support of Morales earlier this week.

WHY YOU SHOULD LISTEN: The consequences of colonialism and its effects on the Indigenous populations are a theme that reverberates across the globe, from the Northern Territory in present-day Australia to the snowy plains of Nunavut in present-day Canada. We usually hear about it in the negative context, with parts of culture, identity, or natural resources being obliterated—or don’t hear about it at all. Bolivia has been a positive example of a country nurturing its Indigenous core for a while now. The way this manifests, both in politics and in cultural affairs, has been an encouragement to the Indigenous people everywhere, as well as the global working class, whose struggle is inextricable from the fight for decolonization.

In addition to the West’s cultural hegemony, the local cultures of many countries have been homogenized and even retrofitted to reflect the dominant, colonial way of life. Exploring Bolivia along with Los Kjarkas allows us to see what culture can be like if the ancestral foundations are not uprooted but instead nurtured. Indigenous cultures are too often discounted as archaic, underdeveloped, resistant to modernity. But what better proves the sheer power of the Native heritage than a traditional song that became the number 1 hit in its dance iteration, sold millions of copies worldwide, and had been covered numerous times throughout different decades? The melody of “Llorando Se Fue” is threaded through the turn of the century and subtly underlines our era’s cultural topography.

But in addition to its fierce social potency, Los Kjarkas are an absolute delight from the musical standpoint: pure, deeply enjoyable music. Whether it’s hearty collective singing or lonely wistful crooning, their compositions, as presented on “Canto a la Mujer de Mi Pueblo,” are a refreshing experience, full of lusty authenticity and tender vulnerability that usually takes multimillion-dollar teams to try and recreate in contemporary pop music. Inhaling it, letting it spread through the listener’s system, is a much-needed respite from the diluted, the altered, the tailored. It’s a breathtaking and dizzying experience, and no wonder: as you listen to the woodwind section of Los Kjarkas, with their weeping pipes and audacious flutes, you’re suddenly thousands of meters above sea level, with the Andean wind blowing in your face, and the puffy multi-layered skirts of the dancers caressing your ankles. A mini-journey to the land where harmony is achievable and the air is fresh: much needed today, and always.

For more content like this sign up for our weekly newsletter

LISTEN TO LOS KJARKAS – LLORANDO SE FUE

Los Kjarkas Performing at the rally dedicated to Evo Morales’s return in November 2020