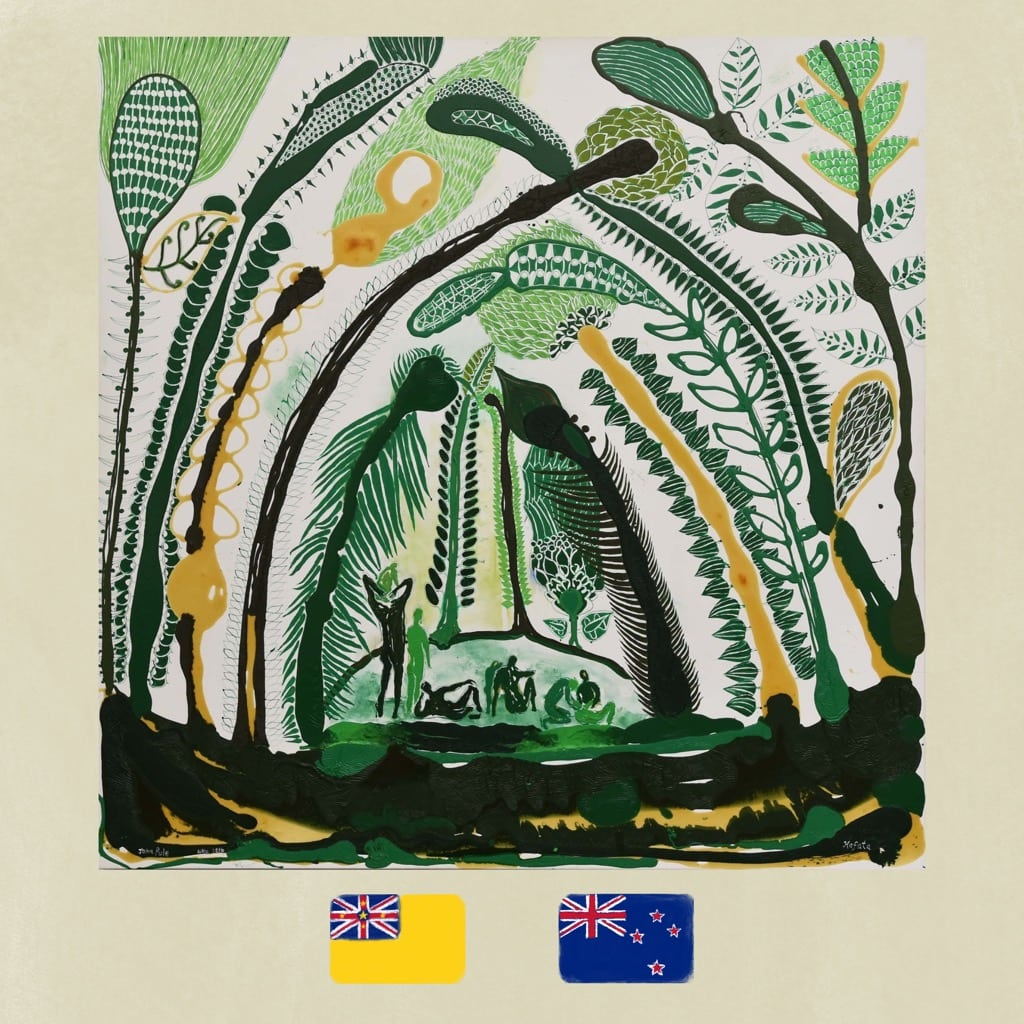

Fierce, otherworldly pieces created by a 71-year old powerhouse of Pacific arts that raise many important questions on assessing art, gender and tradition in the post-colonial space

FROM NEW ZEALAND and TUVALU

WHAT’S GOING ON: Six- or seven-pointed stars explode in a psychedelic array of colors. Shapes border somewhere between organic and extraterrestrial, while meticulous handiwork hints at superhuman ability. So what is this? It’s fafetu, the works of Tuvaluan artist Lakiloko Keakea, who has gradually made the crocheted stars the centerpiece of her art practice that spans 50 years. Despite the ubiquitous use of the star shape, her fafetu differ from each other in the forms that contain stars, as well as size—the biggest one was made using a loom and measured almost 2 meters—color schemes and motifs. Keakea makes each from scratch using freehand, without any patterns, so each design is her vision and the skill to repeat it, combined. And the fafetu are a wonderful reminder of why folk art holds a very special place on the contemporary art scene—because of its timeless power and ability to transcend classification.

WHO MADE IT: Lakiloko Keakea is a native of the Nui Island in Tuvalu, who now lives in Auckland, NZ. Her general artistic vocation is called “mea taulima” in Tuvalu, handicrafts. Even though Lakiloko has been blind in one eye since childhood, she patiently learned from her mother the technique of “koleso”—the traditional weaving of Tuvalu, which is similar to crocheting. Initially, Keakea used it to create garments, but after moving to Niutao, she shifted to objects and more abstract art. And then, through exercises in cultural exchange with other Polynesian women, she discovered her passion for fafetu. She’s now a foremost authority on the star-shaped pieces, and her works have been exhibited and acquired for museum collections. In 2017, Keakea received the Arts Pasifika Award for Heritage Art.

WHY DO WE CARE: Keakea’s art is incredibly appealing from the outside, but once you approach it more closely, the many other facets come into view. Fafetu is an interesting case study for the way we assess art theory from an intersectional post-colonial approach, or how we tie the issue of gender to the issue of art’s value. It’s also a fascinating example of how industrialization alters the way art is produced. Initially, fafetu was created from the leaves of pandanus—a palm-like shrub that finds many uses in the tropical and subtropical regions where it grows—but during her migration and search for a more effective means of expression, Keakea has switched it up multiple times. She had worked with raffia and now often uses a mix of wool, cloth, and synthetic fibers to ensure that her creations reflect her vision in the right way and don’t fade as much as plant-based fibers available to her did. Of course, she goes back to pandanus when the task so requires, but has to import it. Meanwhile, the latest iterations of fafetu made by Keake feature plastic cargo ties and show that the distance between innovative Millenials making jewelry and 71-year-old traditional arts practitioners is dismal.

WHY YOU NEED TO PAY ATTENTION: If you didn’t know what you were looking at, would you immediately think of Pacific crafts? Or would you consider whether these are pieces created by a young contemporary artist incorporating century-old techniques into their uber-fresh work? The point is: there’s not much difference. So while lifting up contemporary, young artists, who bring our attention to problems previously unseen, we need to also acknowledge the older artists from regions remote to the art world’s core, as well as the established art forms in which they work. Keakea is a fantastic example of an uncompromised art practice that she has carried out relentlessly through time and space. A fierce participant in women’s art collectives, Keakea has been living the same truth that has been setting the western art world ablaze in the past decades. The politics of reinforcing traditional cultures in the post-colonial world, the fight for the women’s place in its cultural context, reclaiming handiwork as art within the frame of gender equality activism—these are just some of the points that populate the narrative around fafetu. As multilayered and sophisticated in its ideological implications, as it is in Keakea’s production methods, fafetu is a fascinating art form that continues to evolve right in front of us and a microcosm of how cultures morph and grow.

For more content like this sign up for our weekly newsletter

MORE FAFETUS