It has been three decades since the art world lost Rotimi Fani-Kayode to an AIDS-related illness, but his works on race, sexuality, religion, and difference, remain as fresh and urgent as ever

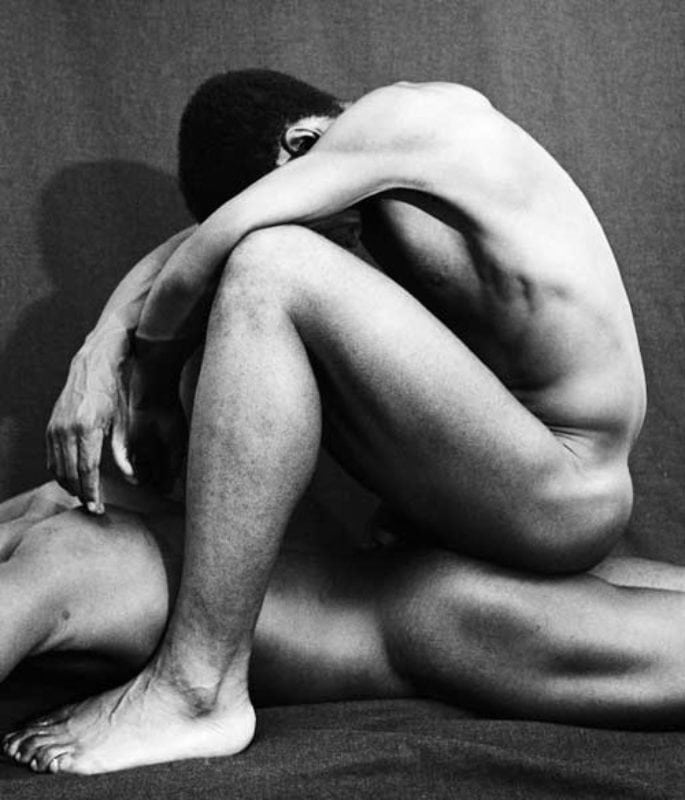

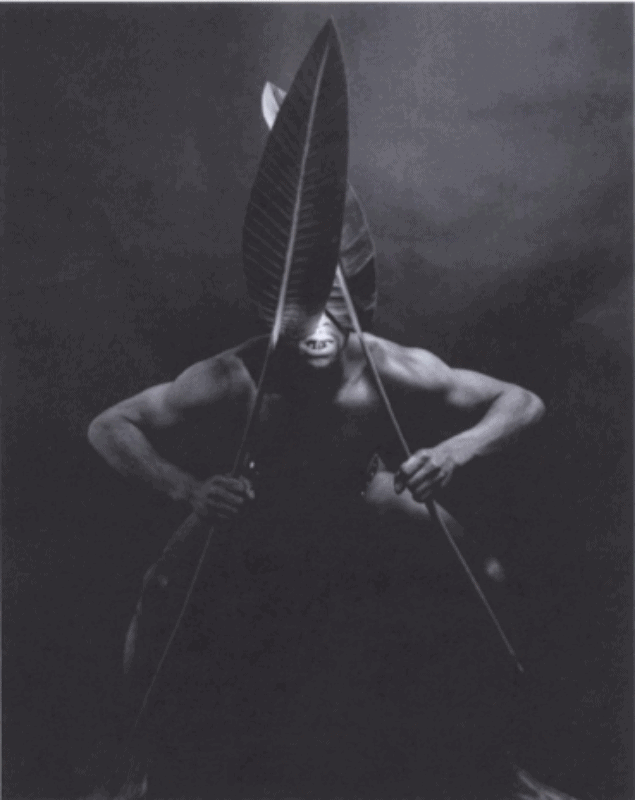

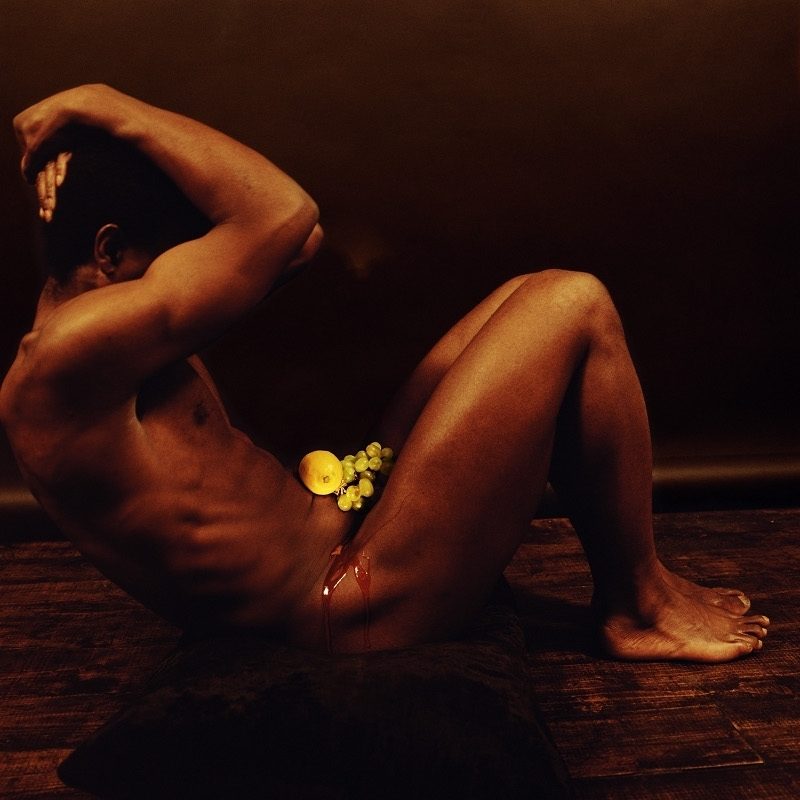

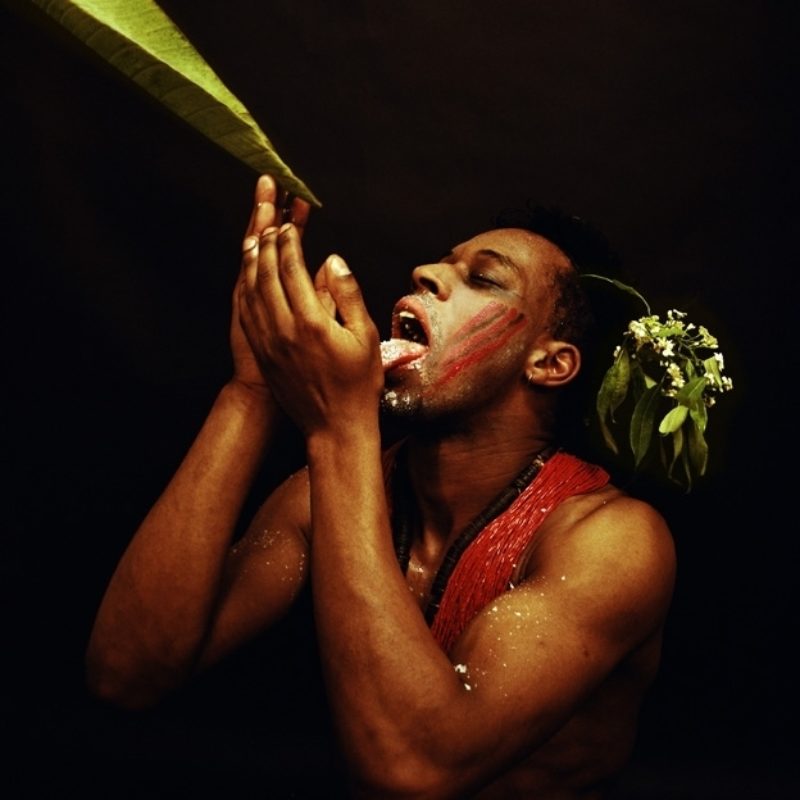

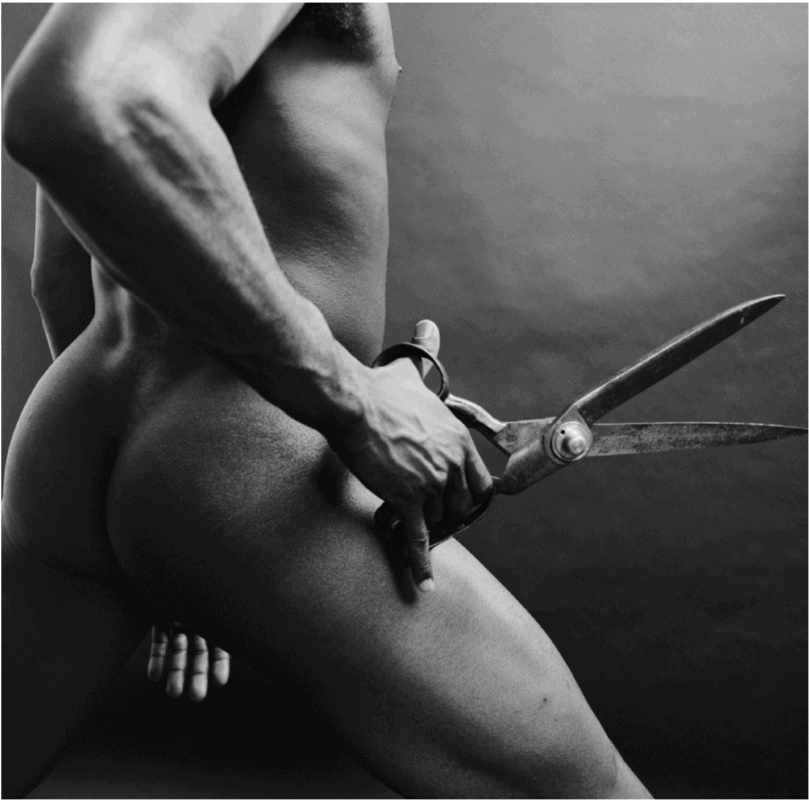

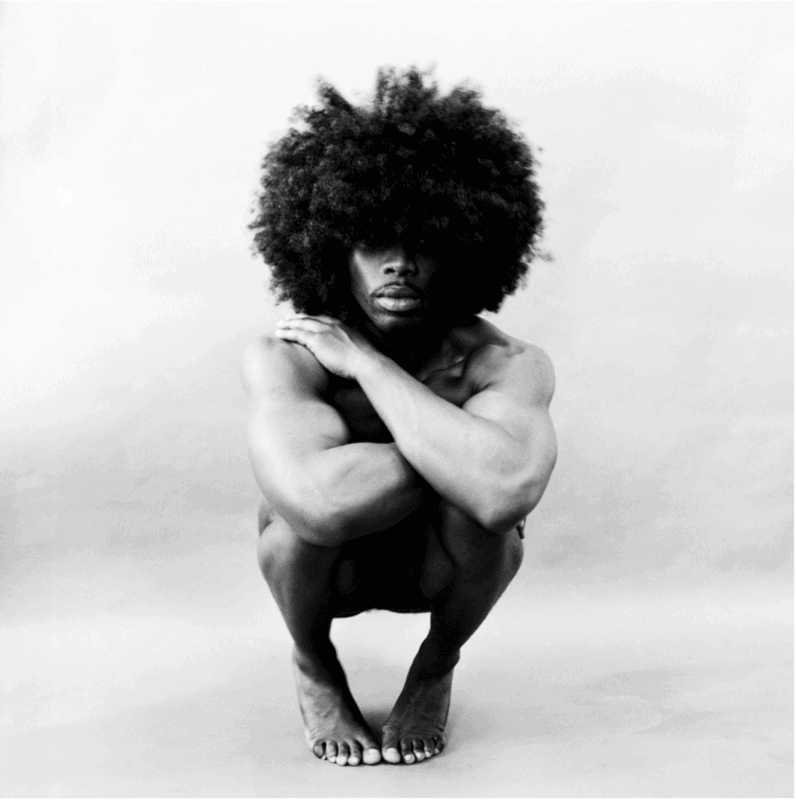

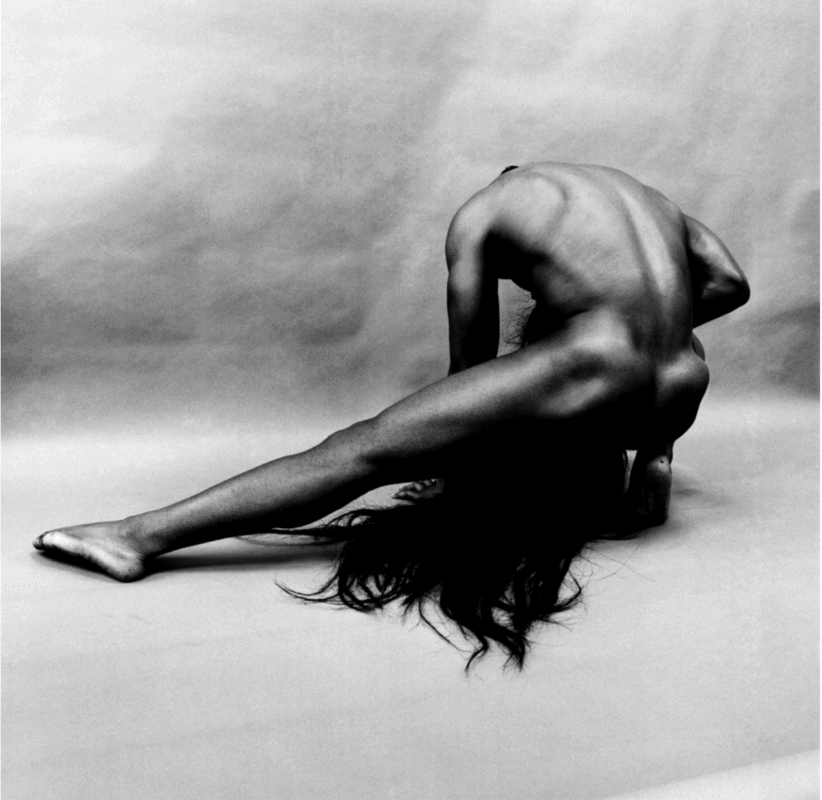

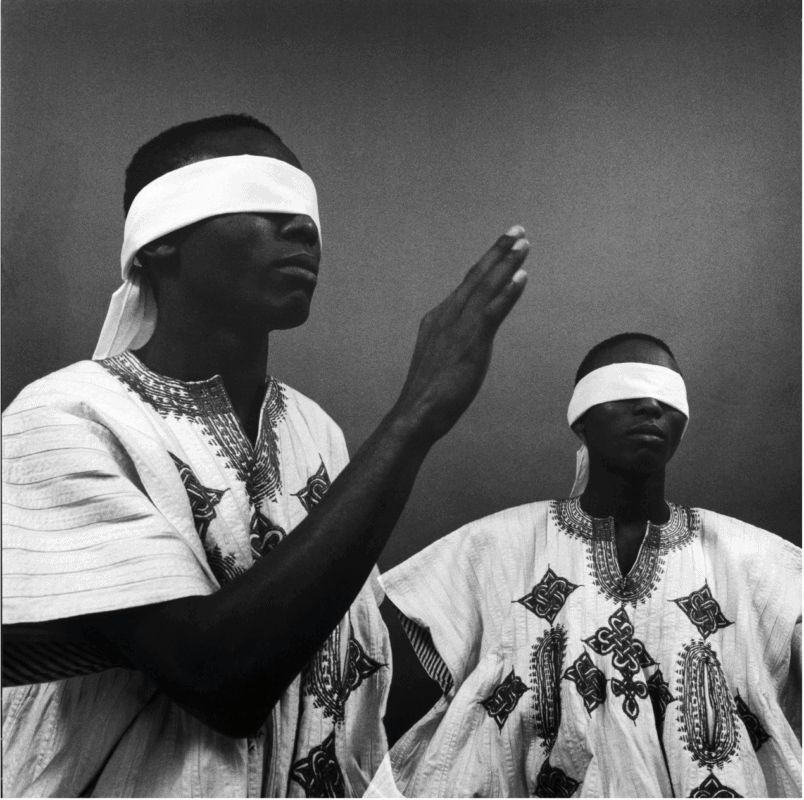

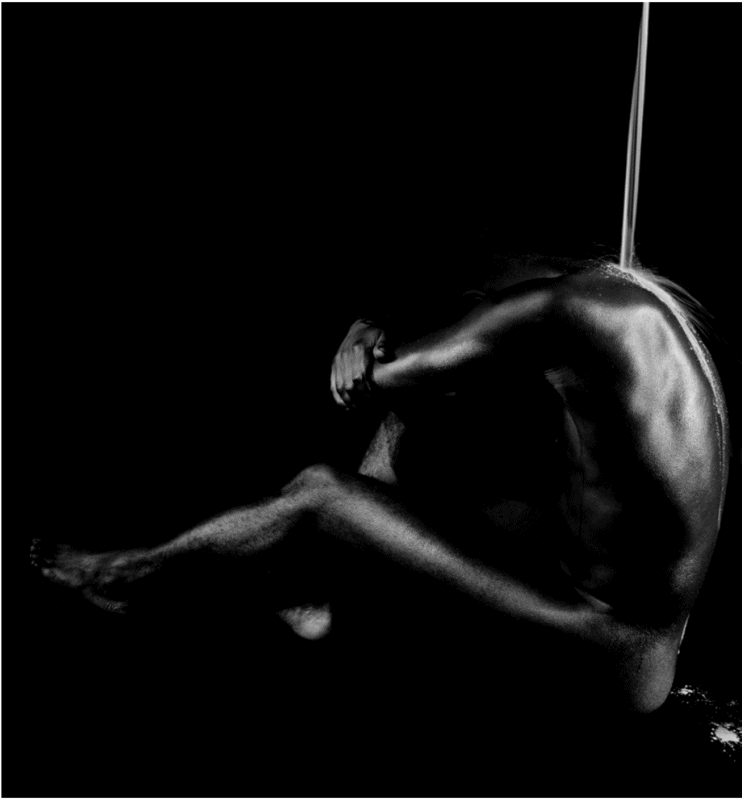

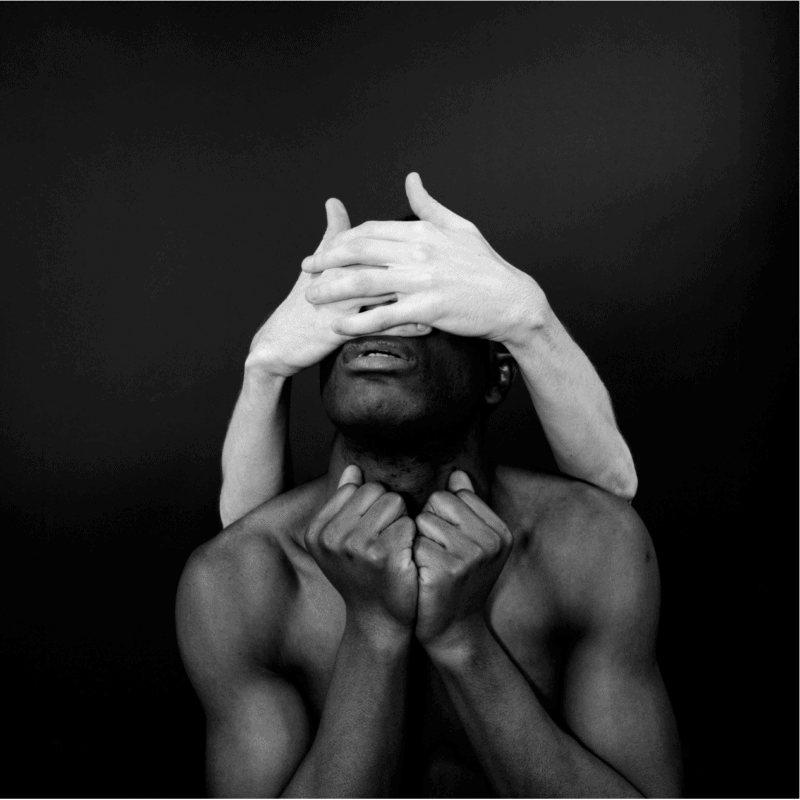

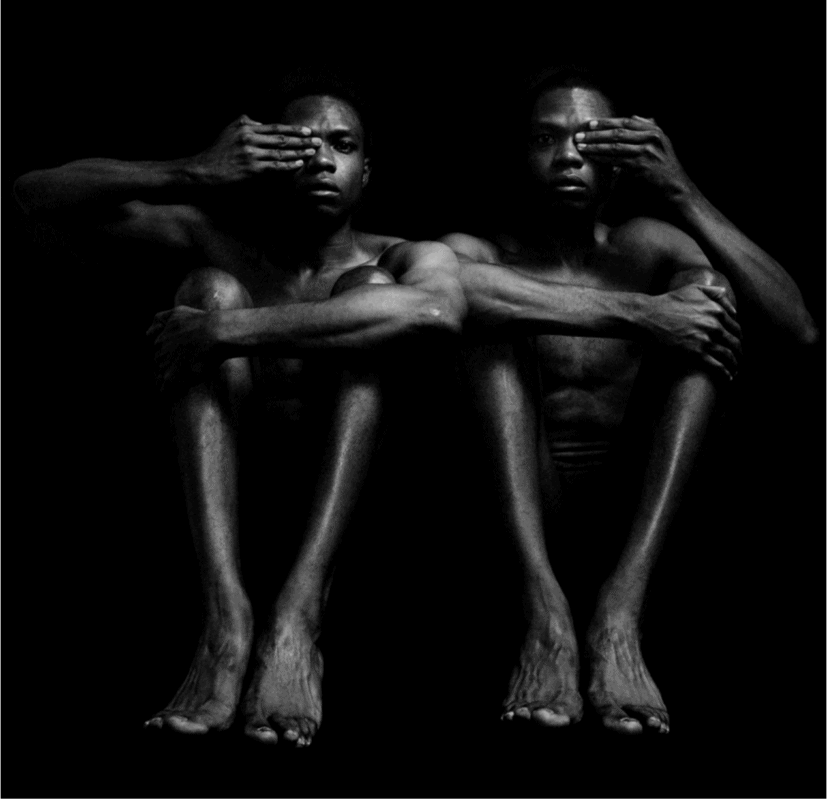

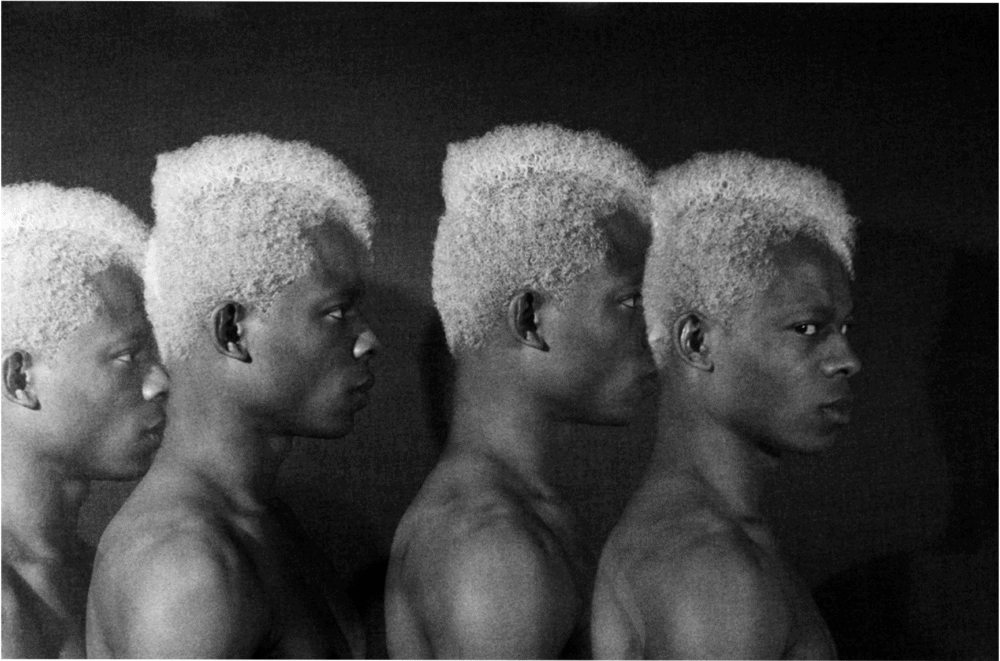

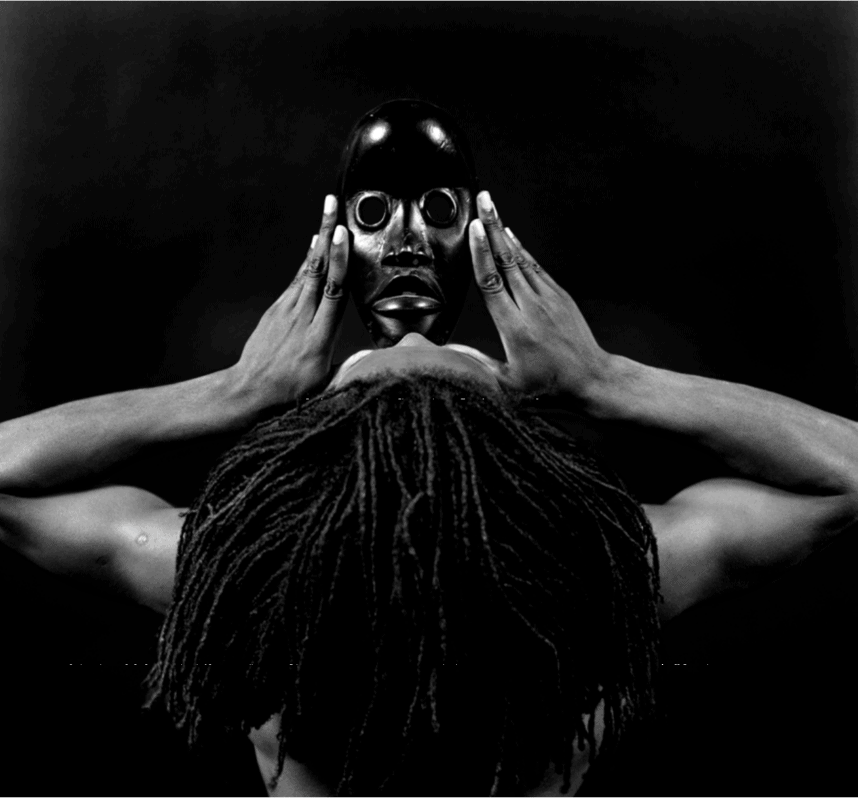

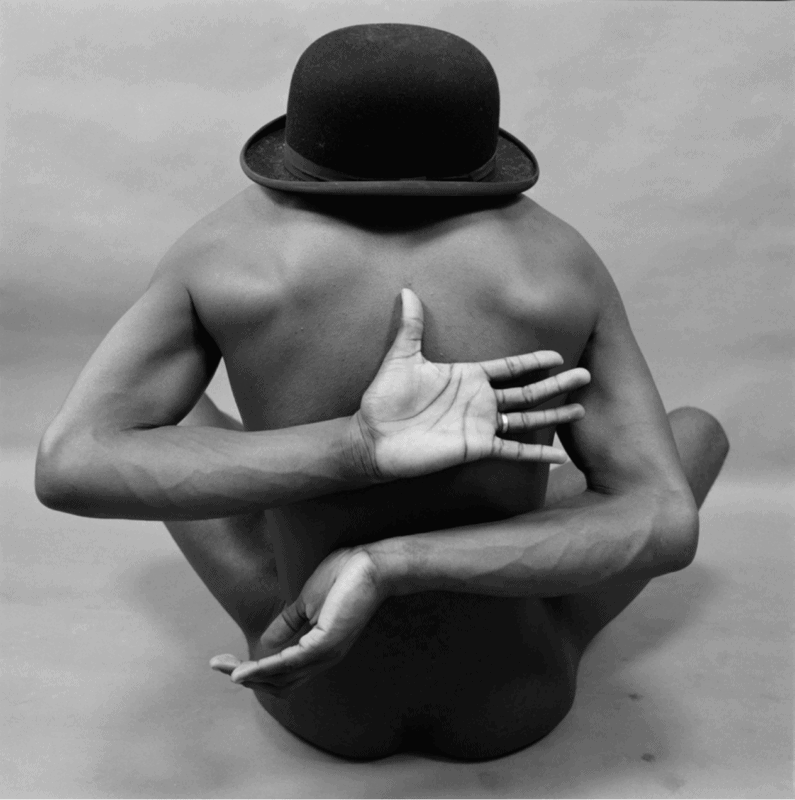

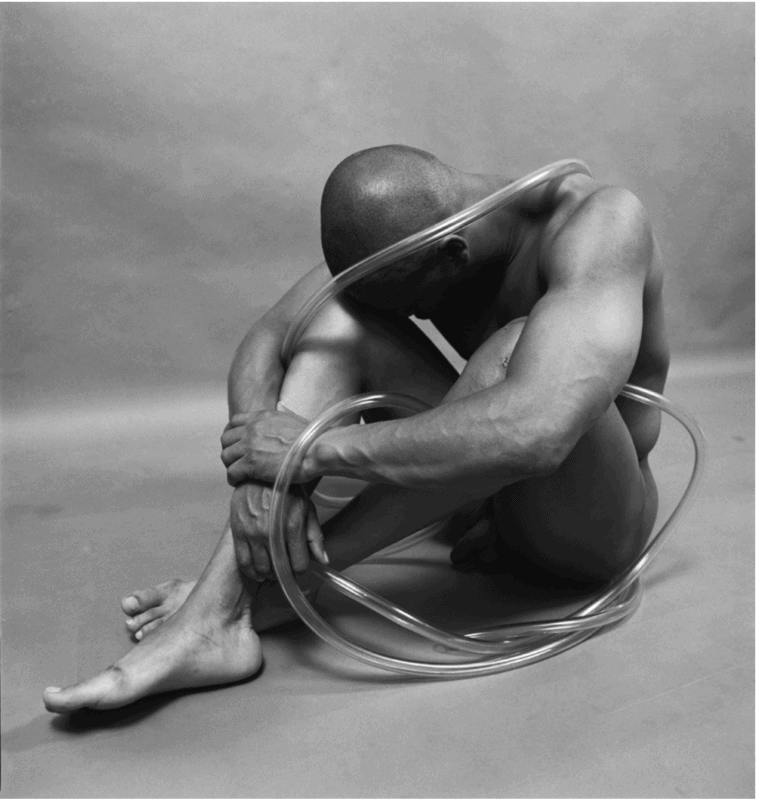

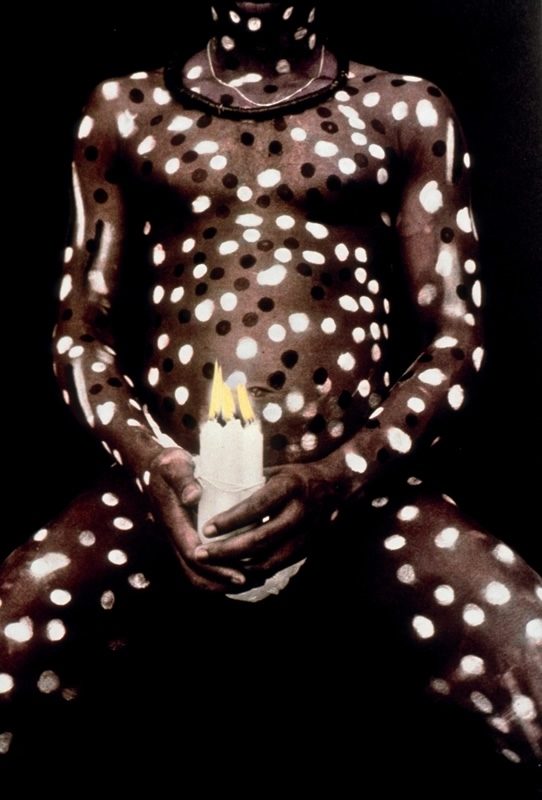

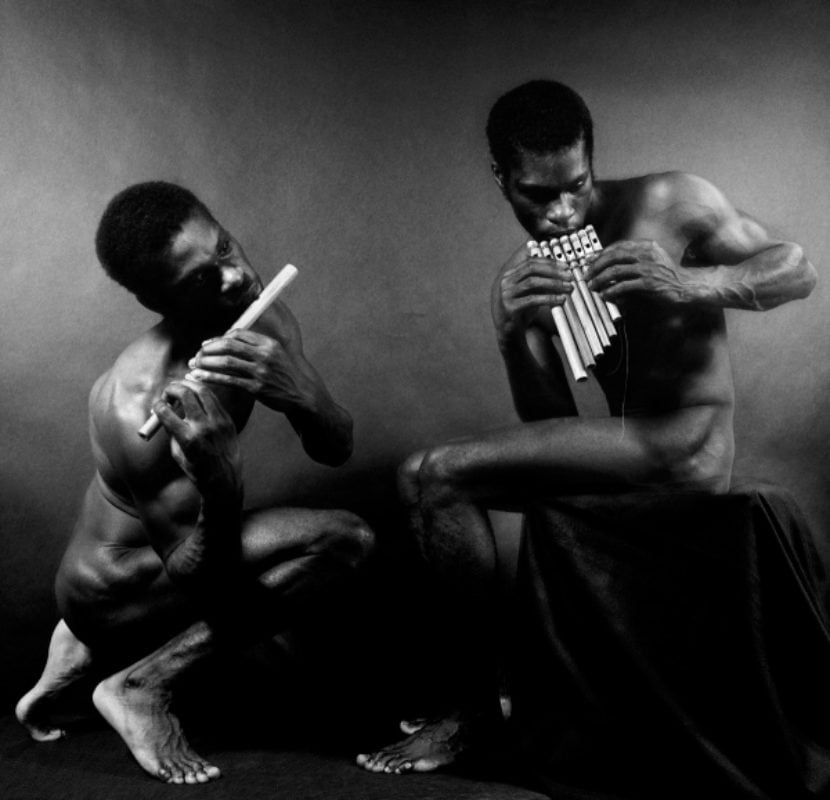

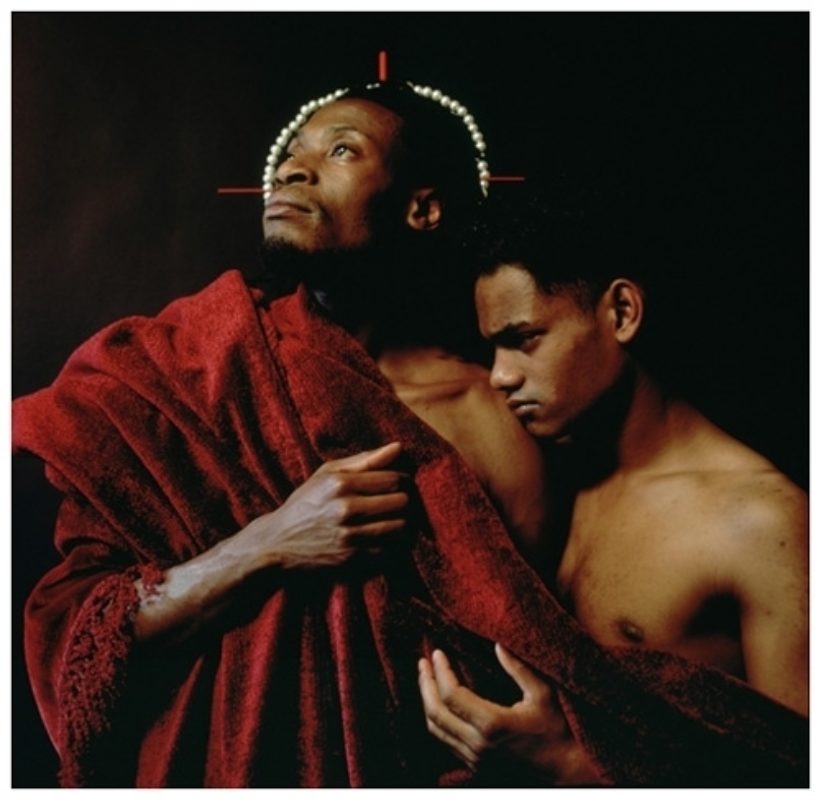

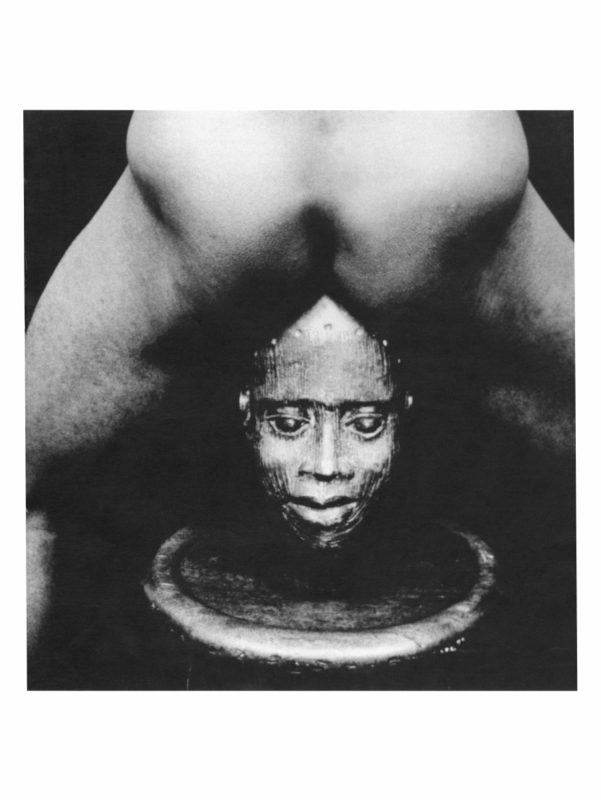

WHAT’S GOING ON: Beautiful black male bodies fill the frames of large-format photographs, the striking chiaroscuro sensuously enhancing the curves in black and white, or bathing them in a warm orange glow of the twilight. Some of the imagery is familiar, the ubiquitous stamps of gay visuality: fawns and saints bound by visible constraints and palpable desire, their faces void of pain, yet full of yearning. But beyond the European frame of reference, something completely unexpected in the homoerotic landscape: masks, feathers, shells, plant wreaths, candles, body paints, and sacrificial tools. Never has the encounter between the artist’s native Yoruba culture and the West, too often underexamined in its most enveloping manifestation in the Middle Passage, been queered as extensively before. The body of work of British-Nigerian photographer Rotimi Fani-Kayode is not vast, as his life and career were cut short by the AIDS pandemic. Yet, it remains a fundamental and unique exploration of a particular crossover of identities and cultures that will be a recurring theme in the 21st century.

WHO MADE IT: Rotimi Fani-Kayode was born in a prominent political clan in Ife, the son of a powerful Yoruba priest Remi Fani-Kayode, who played a significant role in Nigeria’s struggle for independence. In 1966, in the aftermath of a military coup d’etat, the Fani-Kayodes, including the 11-year-old Rotimi, moved to the UK and settled in Brighton. After growing up in the politically-minded religious household, Rotimi left his home to study economics at Georgetown but then ended up at Pratt in New York City, getting an MFA in 1983. Upon his return to the UK, he began his career as a professional photographer, both on his own and with his life partner and collaborator Alex Hirst. Along with a bunch of other photographers, Fani-Kayode co-founded Autograph, Association of Black Photographers, which is still in operation in London’s Shoreditch. Fani-Kayode died at just 34, after suffering a heart attack caused by an AIDS-related illness. Hirst died three years later, also of AIDS-complications. Little is known about Fani-Kayode’s relationship with his family, whether he was estranged or managed to find acceptance before his untimely passing. His younger brother, Femi, has had an extensive career in Nigerian politics, including as a cabinet minister.

WHY DO WE CARE: Yoruba, both as a culture of the people, and religion, is a sweeping set of rich traditions in West Africa, but their influence on the world’s culture, through the transportation of the gold coast’s enslaved individuals across the world, or through later migrations, is only beginning to be adequately addressed. Meanwhile, the way Yoruba heritage comes into play with other parts of one’s identity, such as queerness, is becoming a profound and inspiring topic for the emerging generations of creatives from West Africa. Rotimi Fani-Kayode was decades ahead of the flock, and even though he is lesser known than the queer figures of the Harlem Renaissance, James Baldwin or Jean-Michel Basquiat, Fani-Kayode’s heritage should be accepted as one of the canons of black queer art and theory.

But it is especially priceless as a preeminent exploration of what it means for an artist to grapple with his sexuality, the desired notions of masculinity, religion, race, and inability to belong fully. All those within the African, West African and Nigerian contexts, as well as inside of African diasporas in the West: overwhelmingly spaces where acceptance of LGBTQI+ individuals had not drastically improved since Fani-Kayode’s times, and therefore has made the cultural dialog on the subject all the more necessary. Whereas the majority of queering outside of Africa had been performed using the borrowed vocabulary and toolbox from the Anglo-Saxon or European context, the true liberation is only possible through embracing local cultural norms. Fani-Kayode has provided all the necessary benchmarks, his map of queer desire in the Yoruba tradition stark, prescient and deeply affecting.

WHY YOU NEED TO PAY ATTENTION: It may seem contemporary, and you might even think you’ve spotted a Donald Glover lookalike in one of the photographs, but the whole of Rotimi Fani-Kayode’s body of work was created in the late 1980s. Yet, it has not aged a year in the following three decades. Instead, it has let the times catch up with it and gained potency, yet still evades classification, whether by time, gender, or place of origin. But that’s on the first view because upon closer inspection, a wealth of signifiers from the various, often self-contradictory worlds that Fani-Kayode managed to invade and make to intersect and intermingle, emerge from the scenes of beauty, vulnerability, and power.

A black, African queer Caravaggio of the pre-internet era, Fani-Kayode created his photographs when portraits only began to connote a particular commitment to crossing over, opening up through much danger yet sustaining the self in dignity and grace. He raged, tenderly, gently, against the neoliberal West, the constraints that othering brings, and against classification. And even though the artist’s body is long gone, the works remain, shattering the rigid ideas of what being African, black, Yoruba, Nigerian, British, or gay can and cannot imply.

But as we look upon these 30-year old photographs and marvel in their youthfulness, brevity, splendor, and authenticity, the heartbreaking thing emerges. Even though we’ve advanced in homonormativity, the strikingly femme, yet virile figures in Fani-Kayode’s photographs, that seem full of contradiction and yet appear so harmonious, remain utopian images. The remote prospects of a future where the strength of Yoruba blends with the gentile powerlessness, and fill up an existence between the sky and the inner depths. An elder that many offspring never knew, an eternally youthful poet of lonely resilience that predated his community, a master of capturing otherness and seeing beauty. Rotimi Fani-Kayode is the human to admire this pride month, the artist to evoke as you proclaim that Black Art Matters, and the much-needed icon of queer Africanism that we all deserve.

For more content like this sign up for our weekly newsletter

MORE ROTIMI FANI-KAYODE