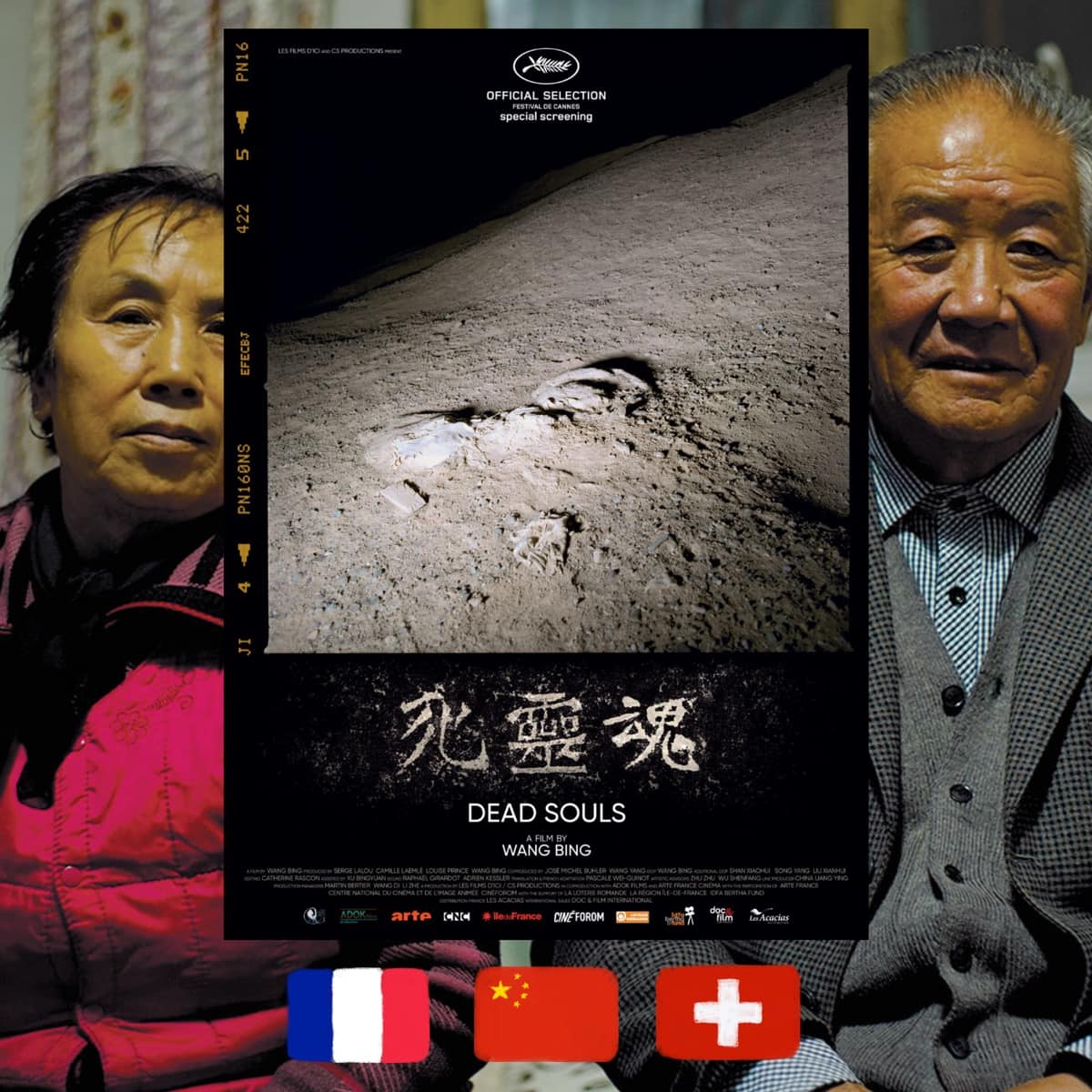

An exhaustive, gutting look at a Chinese internment camp allows us to learn from the survivors first hand. However, what exactly are we as a carceral society taking away from it?

FROM CHINA, FRANCE and SWITZERLAND

WHAT IT’S ABOUT: In the late 1950s in China, the Anti-Rightist campaign was launched to purge the Communist Party of China of conservatives. Itself a reaction to the Hundred Flowers Campaign, where open criticism of the party was encouraged, it became one of the most contentious and impactful political campaigns of the Mao era, although the Cultural Revolution has since shadowed it. Over 300 thousand people were labeled as “Rightists”: some for their former ties to the Kuomintang or their positions in support of capitalism; some for merely criticizing CCP; others as victims of conspiracies against them. Over 3000 of the rightists were sent to Jiabiangou, a labor camp that opened in 1957 in Gansu province near the Gobi desert. The camp quickly turned into a death camp, as overcrowding, mismanagement, as well as the effects of the Great Leap Forward campaign and the Great Chinese Famine on the country, caused around 2,500 of the inmates to die of starvation by the time the camp was closed in 1961. In the 2000-10s, Wang Bing traveled around Gansu and the neighboring provinces to interview around 120 survivors of the camps and record their testimonials. “Dead Souls” comprises of parts of several such interviews, as well as footage from the former site of Mingshui—Jiabiangou’s deadliest farm—and allows for a harrowing look into what life and death were like for the inmates.

WHO MADE IT: Wang Bing is one of the foremost documentary filmmakers in China and the world. He is best known for his another hours-long masterpiece, “Tie Xi Qu: West of the Tracks,” which detailed the erosion of industry in Shenyang, as well as other, shorter documentaries about people living on the margins of Chinese reality. A native of the Shaanxi province, which borders Gansu, Wang had a few relatives implicated as rightists during the campaign. His interest in the subject was spiked when he read Yang Xianhui’s memoir “Woman from Shanghai: Tales of Survival from a Chinese Labor Camp.” As Wang was researching and collecting material for “Dead Souls,” he made a narrative feature film “The Ditch” about the life of Jiabiangou prisoners. “Dead Souls” premiered at the Cannes film festival in 2018.

“Dead Souls” features 17 survivors of the camps, as well as two wives of former inmates, one cadre, and numerous more mentioned in passing or central to the stories. The majority of the men interviewed had been laborers, educators, or civil servants when indicted. The most prominent of them, perhaps, was Li Jinghang, a Christian writer who then penned a memoir “The Time Spent in God’s Grace” and to whom other former inmates still flocked when he was last interviewed for the film.

WHY DO WE CARE: The film’s narrative is stretched out and bulbous, due to the many accounts that it withholds, but each of them reinterprets the same narrative arch: the indictment, the internment, and the individual during and after.

Indictment varies for each particular participant: some had been pronounced rightists through all the official channels; some never had the due diligence carried out. An older man admits that he was not surprised by his sentence because he had his start with the nationalist government but thought that people who were children before the birth of the People’s Republic shouldn’t have been pronounced. But this isn’t merely a takedown of the ideology that laid the grounds for the Anti-Rightist campaign; it is a staunch critique of the justice system as we know it because it always operates under a particular set of rules and legal assumptions, which keep changing every day. Therefore, was the Anti-Rightist campaign any different from the War on Drugs in America? Is being pronounced a rightist, even in the framework where being a rightist is wrong, much worse than being incarcerated for the possession of marijuana, a substance that’s simultaneously legal in various locales?

The interment part of the narrative for each of the interviewees can present the grim reality of Jiabiangou and, most importantly, Mingshui, from various angles, and it is invariably horrid. Unsurprisingly, it turns out that those who had it best were the kitchen employees. However, even their accounts give different angles: some refused to eat the extra that came with their position, others actively took advantage to survive. Is there a way to attach a moral code when survival is at stake? The opinion about those who resorted to cannibalism, devouring the flesh of other inmates, seems to be unanimous, yet there is no consensus about more niche issues. And yet, the entirety of the hellish experiences hinged on the excruciatingly corrupt, broken, and ineffective management on all levels. Examples of it ranged from the inability to keep track of those dying to the government’s designation of the farms as self-sufficient and not requiring outside rations.

These bad managerial decisions caused impossible labor conditions, defeating the purpose of the institutions. As one survivor details, inmates were made to plant crops into frozen winter soil, or as another one recalls, laborers depended on the changing moods of the cadres, some of which were violent and abusive. The wrong decisions also caused dismal living conditions. Inmates slept submerged in holes they dug from the waist up, legs dangling below, and had no water to drink or wash. Another result was famine, where everyone relied on their families, themselves surviving different kinds of hardships at home, to make the trip to the camp and bring them some roasted flour. Otherwise, it was to bloat from hunger and die.

And yet, listening to the stories and connecting the dots, one inadvertently is made to consider the way prisons are being managed today. For instance, in the US, consultancy firms, like McKinsey, are invited to make sure that the prisons, jails, and internment facilities for migration services run smoothly: but the results put the inmates at an even higher risk. Does this mean that problematic management is merely an excuse for a system that wants to be cruel? Or does it mean that there is no way to make a penitentiary facility function well because prison is always based on the idea of dehumanizing those interred within? “Dead Souls” does not answer this question, and it can’t. But it can give you the mental foundation to think about it yourself.

The third and final part of each of the narratives in “Dead Souls” is where each individual briefly assesses the personal toll that the indictment and the internment had had on their lives. Wang’s approach to talking about the reality of internment camps in Mao’s China shows how the inexhaustible struggle for the good of the many leads to the enormous suffering of the individuals. One man lost his wife and descended into alcoholism. Another refused to eat and gave away all of his food to his older brother with kids, surviving by mere accident. The stories are manifold, and yet the suffering is palpable, uniting.

But if we use the same framework to look at contemporary prisons, it becomes quite evident that by using the idea of protecting the many from harm—not merely bodily harm, but harm implied in the many non-violent offenses which lead to incarceration—we destroy lives of individuals that we proclaim harmful. They’re not exactly similar, but compare the experience of a Jiabiangou intimate to that of a man who spent half of his 27-year long term in prison for half a kilogram of cocaine to then die of COVID-19, which festered in overcrowded conditions.

WHY YOU NEED TO WATCH: There is no better way to learn about the past than oral history. “Dead Souls” offers an incomparable privilege to sit face to face with these elders, some collected and eloquent, some rightfully enraged, and listen to their accounts of injustices and indignities suffered and survived. The way “Dead Souls” is structured, with each individual account following the other, instead of being split thematically, doesn’t allow to approach the idea of internment camps as an isolated concept anymore. Instead, Jiabiangou becomes a chorus of personalities, their accounts crisscrossing each other with intersecting truths or blistering contradictions, but arriving at the same assessment: it was terrible, unnecessary, and people died.

This invites the question of why labor camps and reeducation camps are never discussed in the liberal society through the prism of prison abolition? It’s easy to root against the notion of internment camps when they’re presented as outliers, pathologized: denounce them, and they’ll never return. Only they always do, and not merely as symptoms of particular regimes, but regularly. Existing alongside carceral systems means co-existing with the evil they invariably manifest, through its various tools, from thought policing to prison confinement. The COVID-19 pandemic has shown the many facets of how easy it is for citizens to bear the brunt of the carceral society in so-called democratic states. It has also shown how easily life in a penitentiary facility—already precarious as is through the many deprivations that jails and prisons often struggle with even in the world’s wealthiest cities—can become a deathtrap. New York City’s jails, for one, are seeing higher infection rates than anywhere else on the planet.

There are also ranging but not dissonant reports in many countries of the world that show that jails, prisons, and internment camps for migrants, from the slave markets of Libya to the hovels of Lesbos to the cages of ICE custody, are full of abuse, indignities, and suffering. They might be better off overall when compared to internment camps, and none see fatalities at 5/6ths, but that is, admittedly, a very low bar. And in light of all of the tragedies that happen in confinements the world over, the moral ground from which one is watching “Dead Souls” falls under scrutiny. Are we fossilizing the many upsetting and heartbreaking truths of life in internment camps on purpose, to absolve our society or reiterating them?

It’s not clear what exactly Wang thinks about the prison abolition movement. But it’s not exceedingly important here. The question that should be considered is the following: can you sustain a non-abolitionist approach to all penitentiary institutions when all these people who had persevered through hunger, sickness, and abuse in Jiabiangou sit in front of you and talk of their grievous memories? And if their experiences don’t serve to reveal the true colors of systems of justice at place in the world, what are they, then, merely tokens, sad mistakes, aberrations?

“Dead Souls” offers a rare opportunity to learn about the past, but it’s also a tricky litmus test, a kind of exercise in the ability to deflect: what are you taking away from watching it? Are you willing to blame the injustices sustained by the Jiabiangou inmates to a particular time and place, or are you willing to apply the same scrutiny to inmates at your local prison?

A film that requires an open heart and an open mind as much as a capacity for compassion, “Dead Souls” is a rare opportunity to make the world better by just watching a film. But it’s not enough to merely denounce the events in it. It’s crucial to also deeply internalize the experiences relayed and calibrate your worldview with them in mind. Wang Bing started his endeavor of researching the camp, interviewing the elders, and bringing their opinions to the audiences because he didn’t want their memory and the memory of the fallen to fade. However, it becomes the viewer’s responsibility to carry these unforgettable elders in their heart and do everything in their power to make sure this doesn’t repeat in any form.

Dead Souls (死靈魂), 2018

Director: Wang Bing

For more content like this sign up for our weekly newsletter

WATCH THE TRAILER