An incendiary documentary about three brave men at the forefront of the uprising against Joseph Kabila’s rule shows just how much the protest movements across the world have in common

WHAT IT’S ABOUT: Kinshasa, DRC, 2016. President Joseph Kabila has reached the end of his mandate; however, he is reluctant to leave the post. The streets erupt in an uprising of youth, to which the government responds with violence and persecutions. Meanwhile, the frail opposition leader Etienne Tschisekedi, who has just returned from exile in Belgium, is eyed for the next president. “Kinshasa Makambo,” roughly translated from Lingala as “Kinshasa headache,” follows three activists fighting for their people’s liberation. Christian is a member of UDPS, Tshisekede’s party, who attends the protests like clockwork, often risking his life. Ben is a citizen activist who has just returned from exile in the US, disillusioned with the West and bent on changing things in the protest movement. Jean-Marie is a member of the Quatrieme Voie political movement, who had been in prison and lived through torture to resume his activism with twice the conviction. As the three pursue their hope for a free DRC, sometimes collaborating, sometimes butting heads, the essence of the liberation movement familiar to activists across the world emerges.

WHO MADE IT: Dieudo Hamadi is one of DRC’s most exciting filmmakers. He is actively interested in documenting recent Congolese history, especially narratives set in his hometown of Kisangani. The epicenter of the many skirmishes in the country, from Kabila senior’s coup to overthrow Mobutu to the mass violence between Rwandan and Ugandan forces during the Second Congo War, it has been providing Hamadi with many issues to investigate in his films. And for someone extremely young, Hamadi is very productive. The two best known of his features, “National Diploma” and “Mama Colonel,” are set in Kisangani, while “Atalaku” centers around Kinshasa. After finishing “Kinshasa Makambo,” Hamadi returned to Kisangani: his latest project in the works looks at the aftermath of the Kisangani Six-Day War from the point of view of the victims—his fifth feature of the decade.

The protagonists in the film are all active participants of the Congolese resistance, who all share the experience of being arrested or having to flee for their political convictions. Christian Lumu Lukusa is now the vice president of the youth wing of UDPS, which is also the current president’s party. However, he had been detained by the security forces for an extensive amount of time in the aftermath of the filming. Jean-Marie Kalonji continues his work for Quatrieme Voie, and his struggle, including the numerous episodes of detention, has gained him the title of Africans Rising Activist of the Year 2019. It’s not entirely clear what Ben Kabamba is currently engaged in, but he had been affiliated with Filimbi, which had initially sent him into hiding before the film’s events.

WHY DO WE CARE: Since the film had been made, many things have changed in DRC’s politics. Despite staying in his post as president for two years longer than he was supposed to, Joseph Kabila stepped down. The widely contested elections led to Felix Tschisekedi, Etienne’s son, assuming the country’s leader’s post. The coalition between two men formed and fell apart. The current state of affairs remains challenging for the country’s ordinary citizens, many of whom live in poverty while facing displacement and ongoing armed conflict. And as this review comes out, the citizens of DRC are out protesting against Kabila and his affiliates, again. “Kinshasa Makambo” remains just as urgent as it was in the days of its making: after all, Kabila stepped down but never left the field of politics of influence, and the struggle continues. And it’s especially essential viewing amidst the Black Lives Matter protests. “Kinshasa Makambo” shows quite effortlessly how the world’s problems don’t necessarily differ depending on the country’s GDP: it’s the poor that bear the brunt of whatever executive decisions are made in the corrupt cabinets.

Age is another essential element of “Kinshasa Makambo.” DR Congo is one of the world’s youngest countries, with the median age of its’ almost 90 million citizens at just 17. And yet, the country’s politics are not forged by the young, centered around cabinet deals between men from political dynasties—like elsewhere. Jean-Marie, Christian, and Ben are all young men—Hamadi had expressed regret about not including female activists in the narrative—and yet their only viable option seems to be the ailing Etienne Tschisekedi. Throughout their interactions, the three bicker about it: Christian holding the party line, Jean-Marie sharing a bond with Tschisekedi through their shared experience in Makala prison yet denouncing his willingness to negotiate with the regime, and Ben looking for a reimagining of the situation. And even as the film ends and the men’s struggle continues in the aftermath of Tschisekedi’s death, the question remains: why is it that the young and the poor are always left out of the political dialogue, even though they’re the most affected?

WHY YOU NEED TO WATCH: “Kinshasa Makambo” is a film that must be watched carefully, with much attention, especially if you’re not intimately familiar with the Congolese political realities but really want to make sense of it all. The film’s hectic narrative structure is not easy to penetrate without patience, but a careful viewer will be rewarded with rare observations and nuance.

Yet, even with a superficial viewing, it becomes apparent how some of the issues covered in the film are reflective of political movements everywhere on the planet. Anyone who has ever participated in popular uprisings or grassroots organizing will recognize the many pains of trying to find unity, commonality, and effectiveness within the struggle.

As Ben, Jean-Marie, and Christian interact while trying to find an effective way to keep the anti-Kabila movement alive and productive, they do not always seem to be on common ground. Just like when they assess the efficacy of Tschisekedi Sr.’s candidacy, their outlook at the means of resistance is different. Christian advocates for in-party processes and aspirations for electoral influence, Jean-Marie reaches out to the people to mobilize defiant masses and even gives tactical training to the protesters, while Ben tries to reinvent the uprising’s outreach with unconventional but not necessarily functional ideas, which ultimately land him in hot water with the rest of the gang.

Even though the Congolese politics don’t use the same ideological markers that we’re used to in the industrial countries, the polarization of ideas depicted in the film is reminiscent of the way opposition elsewhere functions, with factions fighting each other, movements splintering and interests clashing. The main question at the end of the film, and, despite the changes, in reality, almost four years after its events, remains to be: how to keep the struggle alive, when results are not achievable for months, years, maybe decades?

Pressing viewing in a world where protests and struggles never cease, “Kinshasa Makambo” will not offer convenient answers. However, it will show just how similar the plight of the working people across the world is. An unmatched opportunity to learn more about the brilliant, resilient, and brave youth of DR Congo, it is an incisive, enlightening and compelling film from a director whose work offers valuable historical documents from Sub-Saharan Africa’s largest country. Come to get informed on DRC grassroots activism, stay for the homemade recipe for tear gas protection from Jean-Marie: it’s a small world, after all, and the police and security forces are killing us using the same methods.

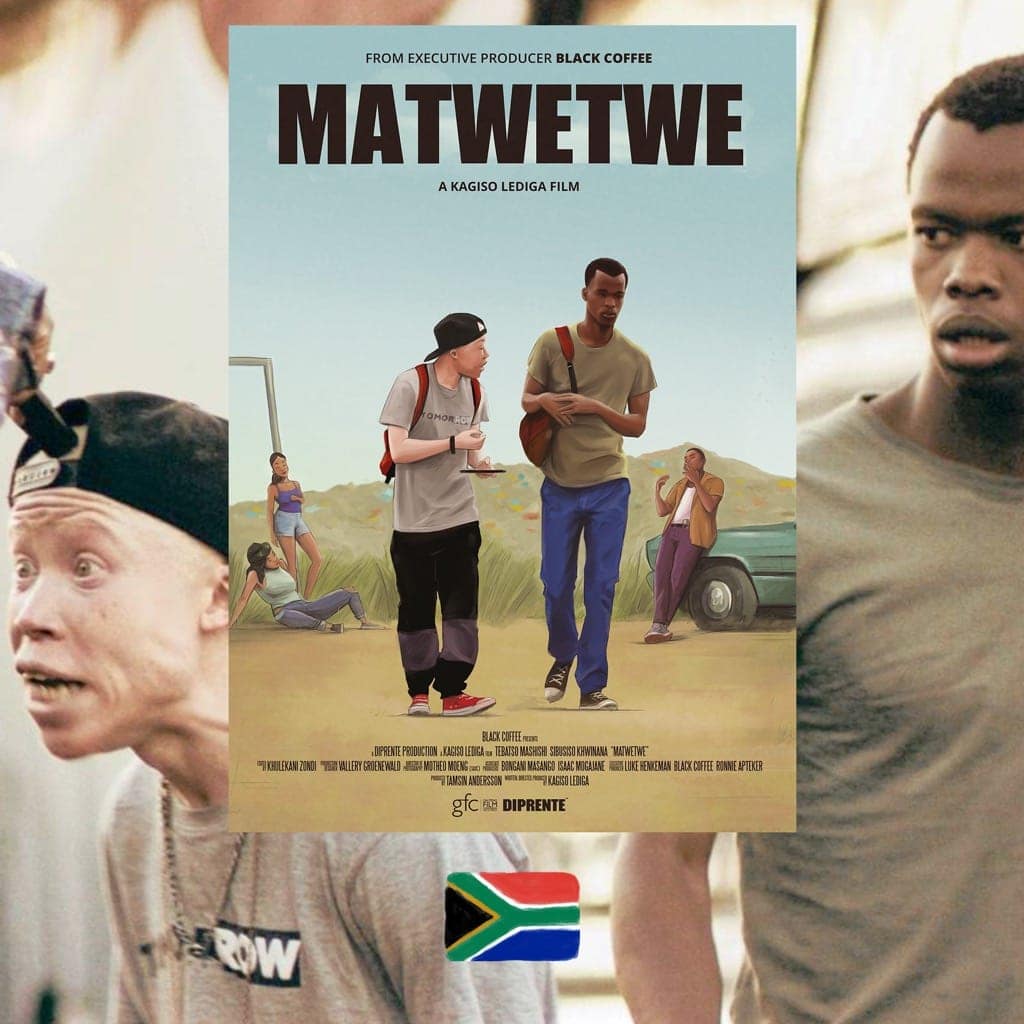

Kinshasa Makambo, 2018

Director: Dieudo Hamadi

For more content like this sign up for our weekly newsletter

WATCH THE TRAILER