As young Colombian director was making a film on his homeland’s visual history, his mother stopped speaking. His film became an exploration of the power of narratives to shape collective perception

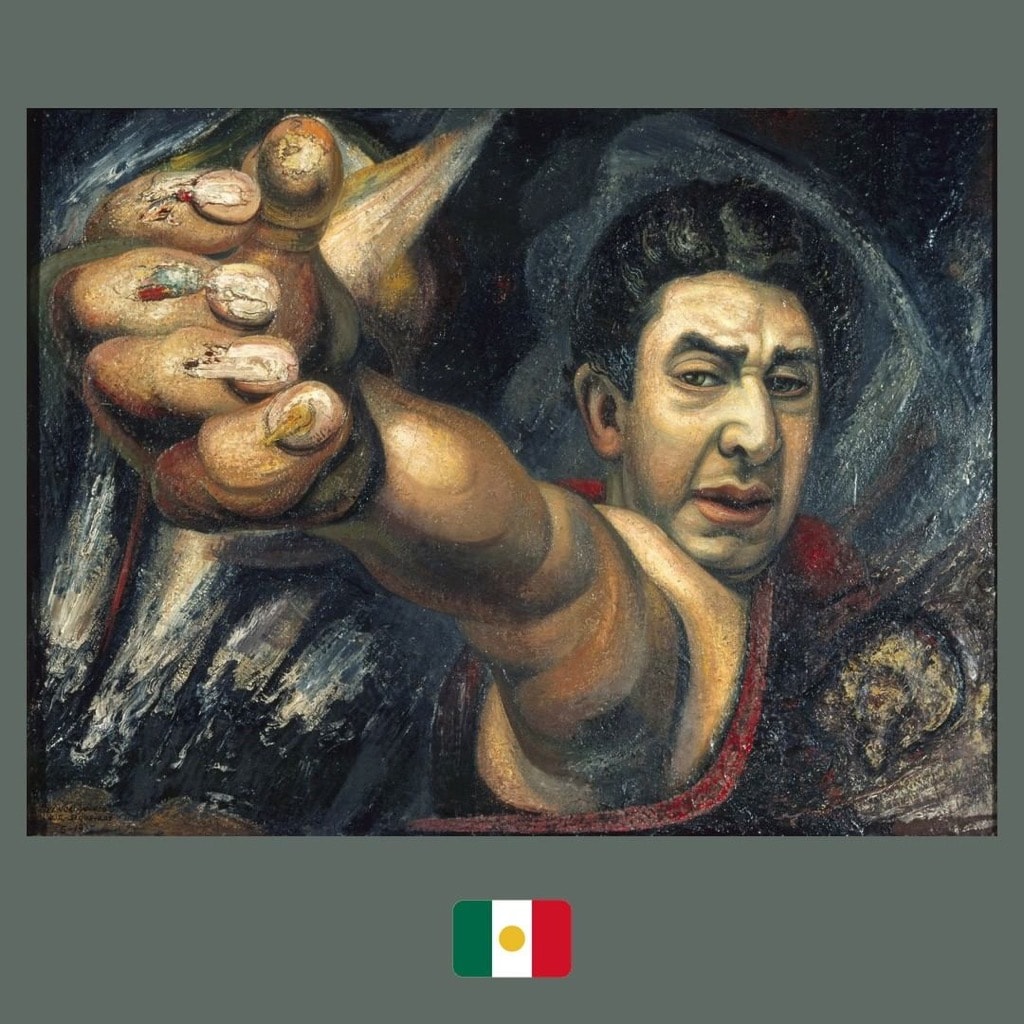

WHAT IT’S ABOUT: After narrowly avoiding an assassination attempt in 1906, the Colombian president Rafael Reyes decided to document the execution of his four attackers. However, that didn’t seem like enough, so Reyes and the photographer Lino Lara agreed to reconstruct the attack itself, with actors playing the roles of the executed assailants, thus creating what “Mute Fire’s” director Federico Atehortúa Arteaga considers to be the country’s first film. He dives deep into the country’s visual history of the 20th century: Reyes’s expedition into the rural lands, the documentation of the Uribe Uribe assassination, the government’s propaganda assault against the FARC rebels in the Colombian conflict. And this enables Atehortúa Arteaga to show how film became an instrument of power and control in the country’s violent political history. However, as Arteaga’s mother, Aracelly, suddenly stops talking during the filming, the narrative widens to examine the family’s own relationship with imagery, memory, and politics.

WHO MADE IT: “Mute Fire” is Federico Atehortúa Arteaga’s debut feature, although he has a decade of short films behind his belt. A graduate of the Universidad del Cine in Buenos Aires and the Universität Pompeu Fabra in Barcelona, he has made films dealing with complexities of Colombian identity as well as exploring the layers of reality in personal stories. “Mute Fire,” which showed at Rotterdam, became a bridge between the two. It brought the political implications of growing up in Colombia, where images of dead guerillas permeated every part of life, with the personal, where an inquiry into his mother’s undiagnosable mutism led him to discover home videos from his preschool days, where he is dressed as a FARC rebel.

Federico’s parents, Aracelly Arteaga and Carlos Atehortúa, make appearances alongside the numerous Colombian historical figures. He co-wrote the screenplay with his brother and collaborator Jerónimo Atehortúa Arteaga, a student of Béla Tarr, as well as Sonia Ariza and Verónica Balduzzi.

WHY DO WE CARE: Manipulation has been part and parcel of the visual documentary arts since their inception. Pioneering photographer Alexander Gardner had to move the bodies of American Civil War soldiers in his groundbreaking shots to achieve the desired dramatic effect. Thomas Edison, as Atehortúa Arteaga shows in the documentary, filmed a reenactment of the execution of anarchist Leon Czolgosz for the assassination of US President William McKinley, because popularizing the electric chair would be profitable for his electrification business. And of course, as the medium became embraced by governments, footage became the easiest way to present truth the way it fit the ruling agenda better. This has been explored thoroughly in some contexts. For instance, everyone knows about the retrospectively disappearing henchmen in the photographs of Stalin’s government, and there is rarely a modern military conflict, where existing footage doesn’t get appropriated for the convenient side. Atehortúa Arteaga both limits and deepens his scope by showing how Colombian governments had used documenting reality to their advantage, both with and without manipulation. It’s such a fascinating, chilling history that one can only imagine what a wondrous feat it would be if filmmakers from every other country dug into the media outlets, governments, and other agents in their countries engaged in the same.

WHY YOU NEED TO WATCH: “Mute Fire” is a film that’s overwhelmingly concerned with truth. However, it is also a mature enough work to realize the futility of a search for certainty, especially where the moving image is concerned. We never learn if Arcelly’s affliction in the film is, in fact, an illness, over which she has no control, or a personal decision, as some of her relatives seem to think. Similarly, Atehortúa Arteaga doesn’t strive to clearly define the good guys or the bad in the historical narratives that intersect in his film. Instead, he is more interested in the power that lies within the act of expression as images or filmed footage are created out of nothing, shifting the narrative focus from the objective possibilities of an undeveloped negative to the subjective certainty of a positive.

The three tenets of contemporary Colombia—the biodiversity of its lands, the political upheaval, and the obsession with soccer—are all explored through how they were presented to the general public. But would the fruit company colonialism be possible, if Rafael Reyes hadn’t pushed for the cultivation of this “hygienic” fruit, as Atehortúa Arteaga explores in his segment on the president’s ethnophotography? Would deeply unpopular right-winger Iván Duque be elected, if not for the communal strife, to distance the society from the existence of the much-dreaded FARC? And would soccer become what it is if there wasn’t a way to package this accessible sport even more democratically?

As the manufactured realities of Colombia are explored in this film, they are juxtaposed to what constitutes Arcelly’s subtle power: the refusal to communicate, the decision to withhold, the acknowledged need for a space of silence and introspection. It’s never specified what exactly the limits to her condition are, and the curiosity that the film raises is a thrilling, alarming experience. In the environment where we expect to be handled everything to constitute knowledge as truth, not knowing feels infuriating. And yet, would we be ever able to know the truth, if the truth was only ever handed to us by those with the power over it?

A discerning, intelligent film, “Mute Fire,” offers an unparalleled dive into Colombian media history. But it’s also universally urgent for its exceptional insights into what it really means to exist in today’s world of well-documented yet convoluted wars and conflicts as a spectator, and what a responsibility watching has become.

Mute Fire (Pirotecnia), 2019

Director: Federico Atehortúa Arteaga

For more content like this sign up for our weekly newsletter

WATCH THE TRAILER