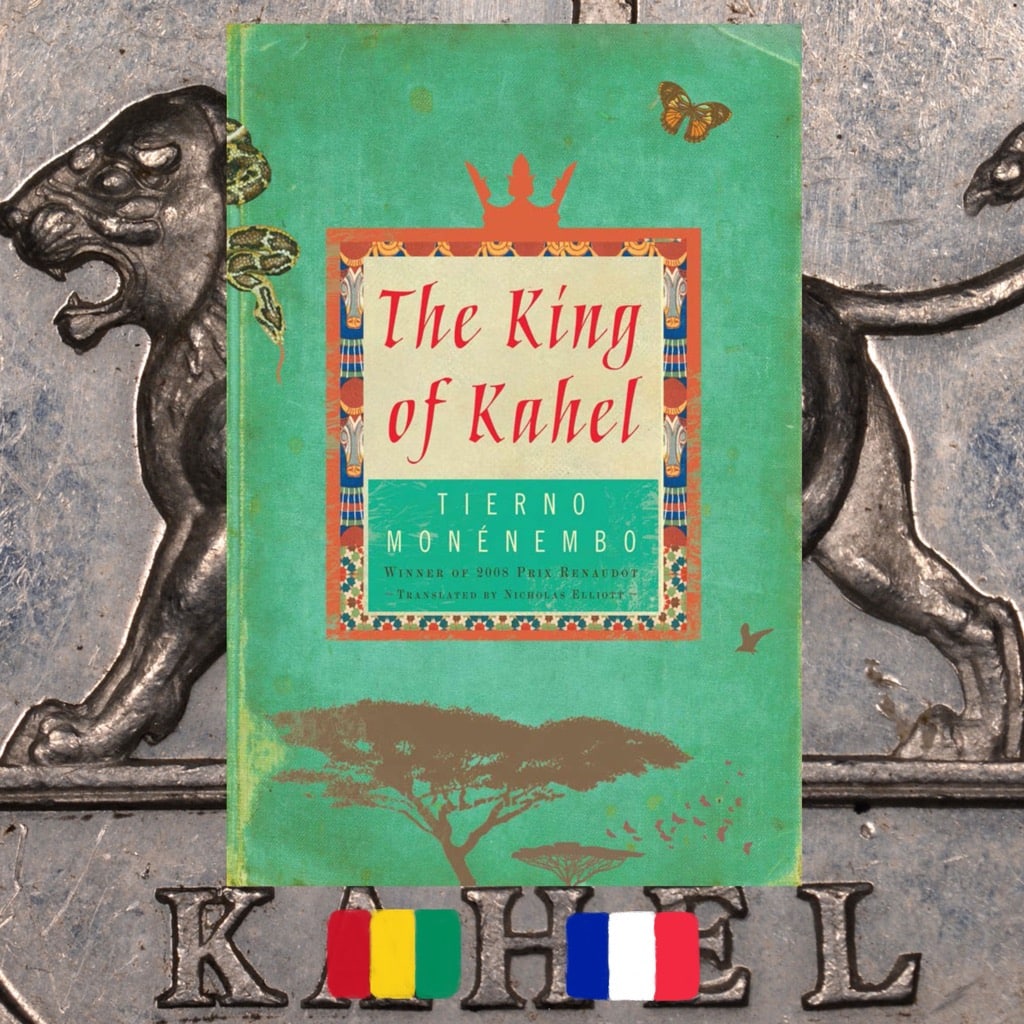

Guinean author subverts the traditional colonizer narrative by crafting a tragicomedy about a Frenchman who wanted to be an African king; offers an unflinching look into the mechanics of occupation

WHAT IT’S ABOUT: In the last quarter of the 18th century, a French entrepreneur and bicycle manufacturer Aimé Olivier de Sanderval traveled to Fula territory in Africa to establish a kingdom, of which he had had feverish dreams since childhood. Eccentric and passionate, in his quest for kingship de Sanderval encountered scores of local rulers as well as French geopolitical players, got caught between many fires, and found shifting success in accomplishing his goals. Surviving sickness, hardships, and threats, but not able to align his vision with that of the Third Empire’s immense appetite for overseas territories, de Sanderval died in obscurity. Yet, the memory of him is retained in the city of Conakry that he helped found. Was de Sanderval just another opportunist of the colonial times, or an idealist who truly sought to find common ground and share the land with the Fulani? Written by a black Guinean author, this fictionalized but meticulously researched biography of a colonizer is an original look into the intricacies of politics in the pre-Guinea territory and France alike. It sheds light on the many factors that made colonization possible.

WHO MADE IT: Tierno Monénembo, also known as Thierno Saïdou Diallo, is a Guinean francophone writer and biochemist, who left his homeland as a young man to escape the Sékou Touré dictatorship. He had since lived in Senegal, Cote d’Ivoire, France, Morocco, Algeria, and the US, but remains invested in the contemporary history of Guinea, plagued by military coups and unjust rulers. A prolific author, Monénembo, loves to explore the nuances of Fulani identity in his work. He first wrote about de Sanderval in his novel “Fulani,” and then became further interested in this ambiguous figure, who considered himself a Fula towards the end of his life. He enlisted the help of de Sanderval’s grandson, who himself was born in Guinea, where his father and Aimé’s son returned after de Sanderval-pére’s death. This way, Monénembo was able to immerse himself in the family’s oral history and combed through the extensive archives to be able to trace the many events and nuances of the ambitious colonization project which never came to be. For “King of Kahel,” Monénembo was awarded the prestigious Prix Renaudot in 2008, becoming the third writer of African ancestry to get it, after Ivorian Ahmadou Korouma and Congolese Alain Mabanckou. The translation of “King of Kahel” became the inaugural book published by AmazonCrossing, the foreign literature imprint at Amazon Publishing. Its translator, Nicholas Elliott, is based in New York and is not exactly easy to pin down. He has translated a diverse array of books; directed a bunch of short films (some of them produced by Brian Molko); works as a Locarno film festival programmer, New York correspondent at Cahiers du Cinéma and contributing film editor at BOMB magazine. Admittedly, he was drawn to the project of rendering “King of Kahel” in English after becoming enchanted with the novel’s daring look at colonialism.

WHY DO WE CARE: Very recently, we started exploring the genre of colonialism satire wth the remarkable animated film “This Magnificent Cake!” and “King of Kahel” is a fitting continuation of this survey, only, in this case, the satire stems from a faithful recounting of real events, not just metaphor because history can be a bizarre animal even without embellishment. The very droll tone of the book, coupled with meticulous accounts of all of de Sanderval’s endeavors and the imitation of the valiant explorer narrative, is pitch perfect. Therefore, you may find reviews full of indignation with Monénembo for valorizing the colonizer. But the beauty of “King of Kahel” is that it doesn’t seek simple takes. De Sanderval is a skillfully rendered protagonist: the reader, along with Monénembo himself, can’t resist admiring him for his industriousness, diplomacy, and persistence. However, all these qualities are also hard to separate from his overwhelming white male entitlement, which led him to Africa in the first place. Was de Sanderval a colonizer who cared enough to take the local culture, leadership, and customs into consideration? Yes, and this open-mindedness was one of the things that cost him his place in the empire-building juggernaut. But wasn’t he also a French man who sought to invade spaces that didn’t belong to him? Absolutely. Another parallel that comes to mind is a comparison with “The Meursault Investigation,” a subversion of “L’Etranger”. Only “King of Kahel” is even more complex than a post-colonial reclaiming of the narrative. Monénembo doesn’t try to recount the events that transpired around the Fouta Djallon mountain range at the turn of the century by using one of the victims of colonization as a mouthpiece, which would too conveniently skew the moral appraisal of the situation. Nor does he seek to try and saddle too many POVs at once. Instead, by maintaining a close third person from de Sanderval’s point of view, Monénembo can show many more facets of colonization of African than just white privilege, black victimhood, and imperial greed.

WHY YOU NEED TO READ: “King of Kahel” is not precisely a submissive kind of book. It’s rich in content, has a vast supporting cast who always wait behind the curtain to jump out at the reader unexpectedly—I was glad to be reading on a Kindle, with the X-ray tool enabled—the reader’s head might begin to spin with the attempt of trying to keep scores. But this dizziness and disorientation only serve to further assert the novel’s plot as a successful emulation of what colonization really was in the process. A hazy, busy, and utterly absurd global commotion with a sequence of people shitting their bowels out in the bushes while waiting for yet another covert intrigue to resolve. “King of Kahel” reads like an opera, in part because Monénembo’s language, effectively rendered by Elliott into English, has supple, descriptive plasticity to it, partly because of the delightful pathos that permeates every scene. Whether it’s de Sanderval alone, lamenting the lack of appreciation for his vision from the government, or crowds of Fulani elites bickering about their self-interests before picking which part to play in the process of colonization, or European, mostly French interjectors who dismiss the other two factions as obstacles to full control, the characters crackle with pathos, ridiculousness, and complicity. The novel does leave wishing for something extra: for instance, a more detailed look into the workings of the Fulani kingdoms’ courts, outside of their interactions with de Sanderval: a sophisticated lot, they navigate a diplomacy of stupefying complexity, which de Sanderval can approach, because he doesn’t mind listening, but the French colonial government dismisses as too cumbersome. But this is a preoccupation for another of Monénembo’s books. “King of Kahel,” simultaneously sprawling in its goals and intimate in its faithfulness to de Sanderval’s struggles, seeks to pose questions about the nature of involvement of parties in colonization and to speculate on the different approaches that could have been taken by all factions. And it is through inclusive, pitiless, and incisive narratives like “King of Kahel” that understanding of the minor screws that enable imperialism is possible: and perhaps a better understanding of it will also help us prevent it further?

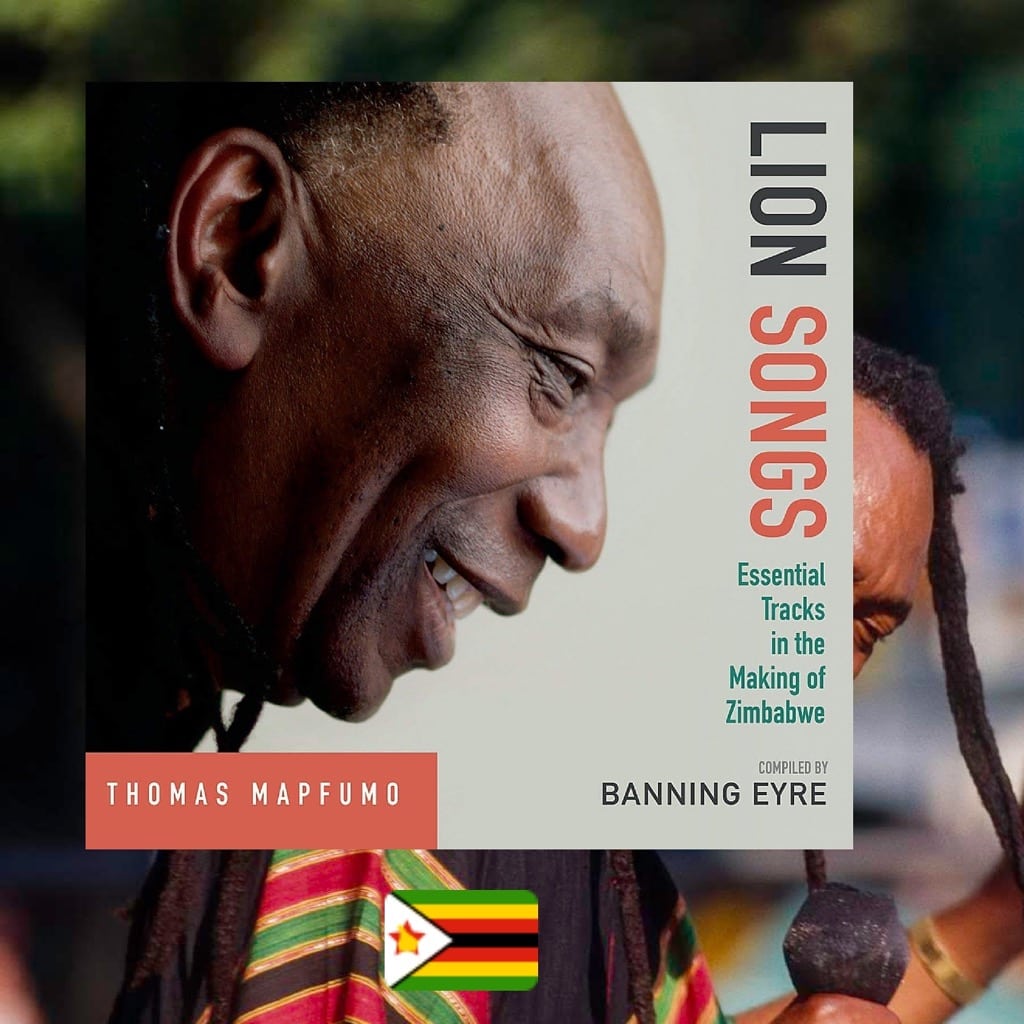

Tierno Monénembo, King of Kahel

Translated by Nicholas Elliott

Published by Amazon Crossing in 2008

For more content like this sign up for our weekly newsletter