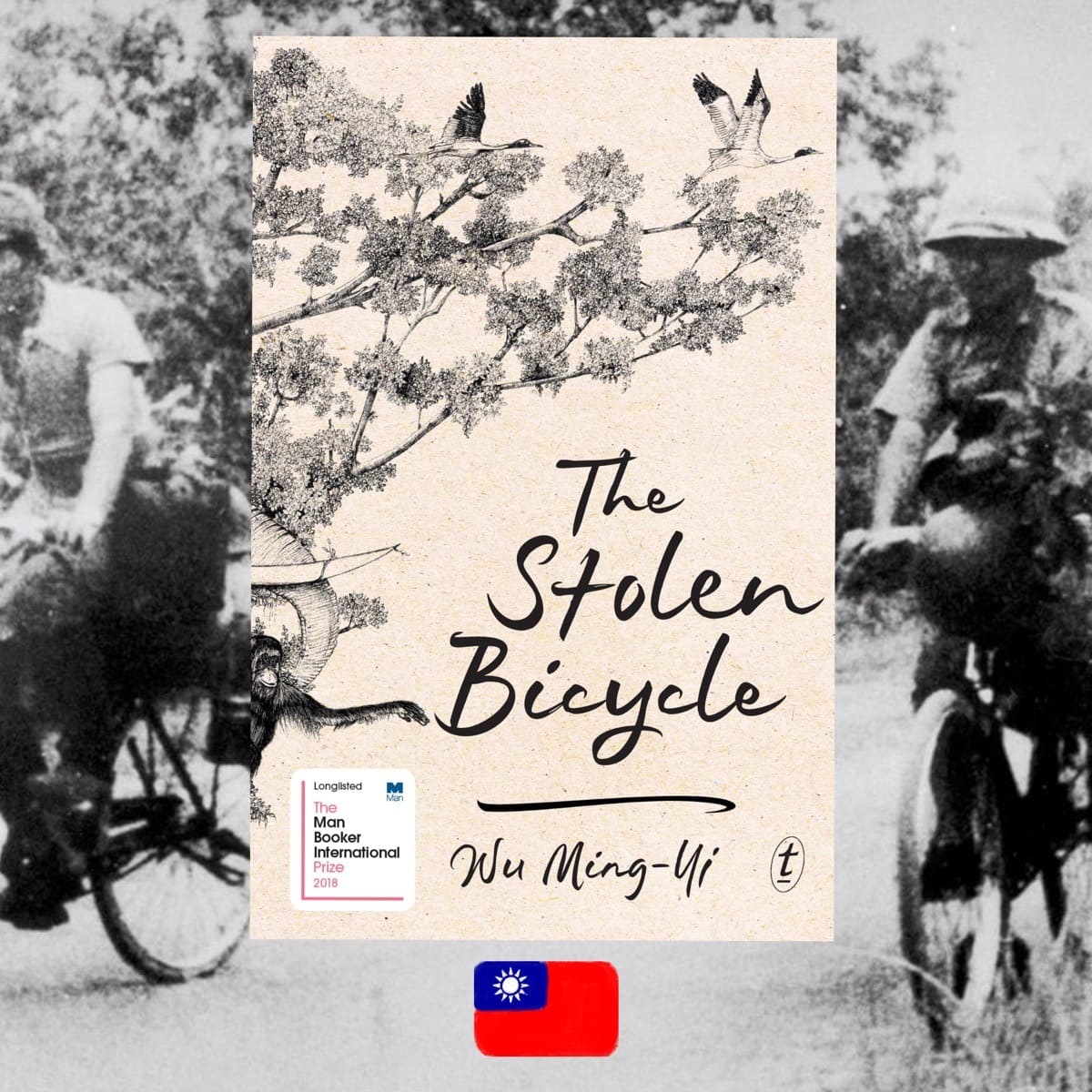

A highly imaginative novel rooted in the personal and historical comes together as a multi-faceted vision of Taiwan’s past and distills Taiwanese identity out of wars and calamities

FROM TAIWAN

WHAT IT’S ABOUT: Taiwanese writer Ch’eng, a fictionalized version of Wu Ming-yi, had written a novel about the disappearance of his father—also rooted in reality. But he realizes that his inquiry is not over when a curious reader asks whether Ch’eng had ever considered trying to locate the bicycle which the father used right before vanishing. Fascinated with the history of “iron-horses,” as they’re locally called, in what is now the world’s bicycle production capital, Ch’eng embarks on an obsessive journey to locate his father’s bike, which he can recognize by the serial number on the seat post. Through antique stalls and message boards, Ch’eng encounters illustrious characters and, with them, gets deeper into the history of Taiwanese bicycle manufacturing, as well as the surrounding region’s history at large. The island’s landscape of colonization and wars is explored, where humans, bicycles, cultures, and nature have collectively endured.

WHO MADE IT: Wu Ming-Yu is one of the leading writers in Taiwan, his fiction being translated into multiple languages, and his non-fiction books on butterflies, which he also illustrated himself, well-known in the Chinese-speaking world. A language scholar and an environmental activist in addition to his writing, he first gained prominence with his novel “Sleeping Route,” which prompted the bicycle fanmail that would inspire “The Stolen Bicycle,” however, it had not been translated into English (yet). Instead, Wu’s English debut came with “The Man with the Compound Eyes,” a parable that juxtaposes indigenous identity, industrialization, and ecological concerns.

Originally from Canada, Darryl Sterk is a translator, linguist, and university professor, who currently teaches translation and interpretation to grad students at National Taiwan University. His research in the field of indigenous identities and languages of Taiwan, as well as his previous collaboration with Wu on the English-language rendering of “The Man with the Compound Eyes,” have made him the perfect fit for the translation of “The Stolen Bicycle.” He has also translated novels and short stories by writers from Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Mainland China.

In 2018, “The Stolen Bicycle” was longlisted for the Man Booker International Prize.

WHY DO WE CARE: Micro-histories are a fascinating way to learn about a particular place, and because “The Stolen Bicycle” simultaneously offers a bunch of them, the reader ends up with a veritable kaleidoscope through which to look at Taiwan. At the forefront, of course, is the history of bicycles in the island’s history, enhanced with Wu’s own gorgeous illustrations, that offers the first key to the semiotic nuances of identity: before the cultural osmosis could properly occur, the word one used to connote a bicycle in Taiwanese or Mandarin could tell you a lot about the person’s background. But as the linguistic difference was smoothed over and people started to use words without much discretion, so did the bicycles evolve, from the retro Luckies, just like one that belonged to Ch’eng’s father to today’s ubiquitous GTs. But the tireless archivist, Wu, doesn’t step away after laying out centuries according to bicycle production, and he does the same exhaustive exercise with butterflies, cameras, Japanese presence, wars, elephants, lost father figures, and missed loves. It’s as if Wu believes that by accumulating enough stories, he can reconstruct a reality. “Stories exist in the moment when you have no way of knowing how you got from the past to the present…As you listen to them, you feel like they have been woken up, and end up breathing them in. Needle-like, they poke along your spine into your brain before stinging you, hot and cold, in the heart,” he writes in the novel. And then adds in the postscript: “I write because I don’t see the world clearly. I write out of my own unease and ignorance.” And indeed, sometimes “The Stolen Bicycle” feels misty. One of the novel’s most striking parts, when an elephant travels through the dense Burmese jungle in the Pacific theatre of World War II, has this hazy, dreamlike quality. The magic that Wu creates with words and emotion overshadows the horror of war, by allowing the reader to float above, on the level with the elephant’s head, away, but not secluded from danger. The same vagueness is present in the other stories that don’t necessarily place in the novel’s overall puzzle until later: the long bicycle rides of A-hûn, the bizarre scuba diving that Abbas undertakes with Old Tsou. But as the novel wraps up, Wu invites the reader to take a step back, and the miscellany of stories blends into one affecting wonder.

WHY YOU NEED TO READ: “The Stolen Bicycle” is an absorbing, erudite novel that uses its many facets—historical insights, linguistic ability, incisive humanity, and the author’s dazzling illustrations—to open a singular portal into Taiwanese identity. Wu himself is a dedicated scholar of his homeland’s many permutations, and even though he tries to put a brake to his voluptuous intellect by constructing the more laidback person of Ch’eng, the result is still palpably brilliant. Already obsessed with material preservation of Taiwanese history as an antique enthusiast, the novel’s protagonist Ch’eng also turns out to be a passionate collector when it comes to oral history. The accounts he gets from the various characters—an indigenous photographer Abbas, an older Japanese woman Shizuko, A-hûn’s daughter Sabina, even his own mother—unfold into multilayered panoramas of Taiwan and the many ebbs and flows surrounding the island that joined to mold it into a unique entity. In the original Mandarin edition, “The Stolen Bicycle” is the embodiment of this complexity, a patchwork of languages and dialects, with the indigenous Taiwanese language leading the way. And even though Sterk, a committed observer of the Taiwanese lingual polyphony, poured his heart into making sure to preserve the intricacy in his translation, English is not potent enough to do it justice. And yet, the splendid chorus still appears, and as the many narratives come together as one towards the end of the book, the multiplicity of humanity is propelled to the forefront. It may not carry the novel’s original weight, but the English version of “The Stolen Bike” manages to stubbornly accomplish the idea at which the original only aimed to arrive towards the end. The transcendent commonality of experience, where wars and calamities try to eat away at the connecting tissue of humanity, for language to put it back in place.

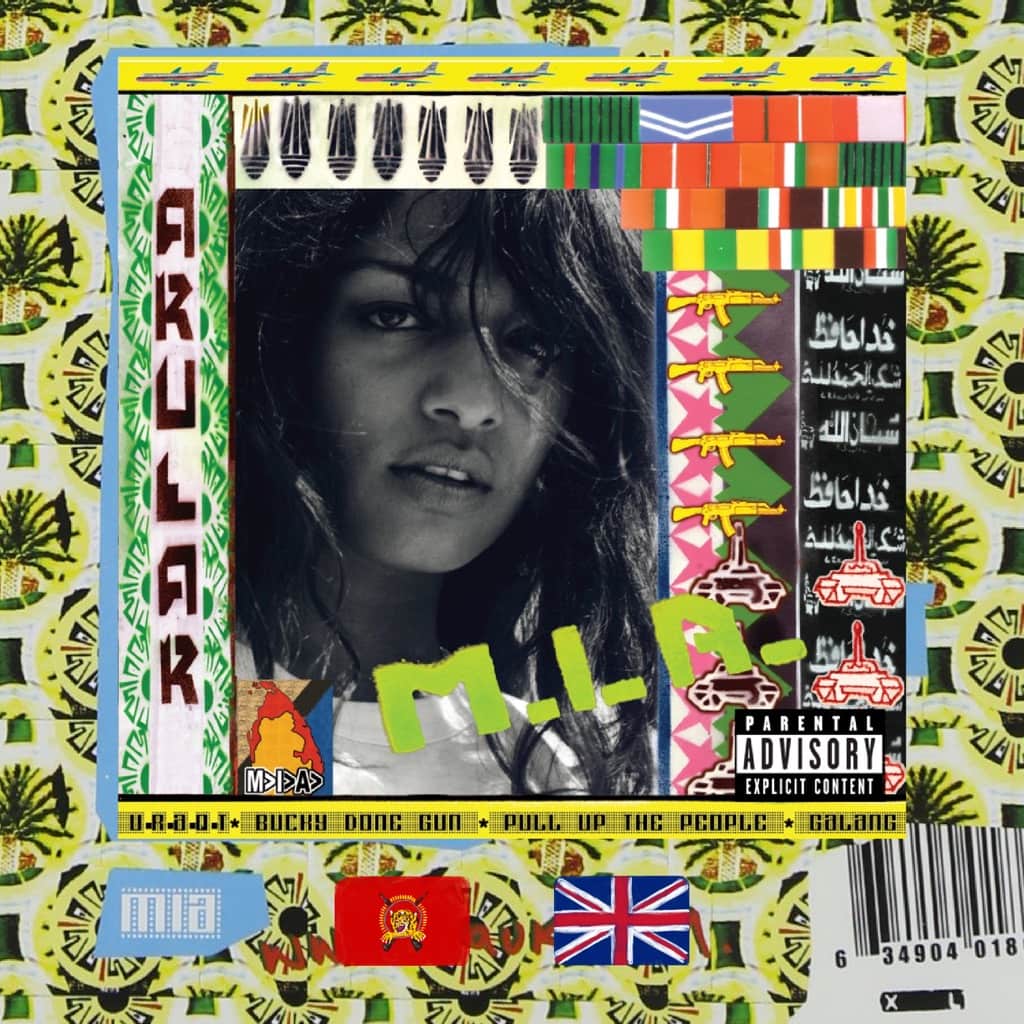

Wu Ming-yi, The Stolen Bicycle (單車失竊記)

Translated by Darryl Sterk

Published by Text Publishing in 2015

For more content like this sign up for our weekly newsletter