A powerful portrait of a man who tried to take down the Brazilian Military Dictatorship is necessary viewing on the question of violent resistance

FROM BRAZIL

WHAT IT’S ABOUT: In the late 1960s, as Brazil struggled in the firm grasp of its Military Dictatorship, Carlos Marighella, a lifelong Marxist-Leninist and communist leader and writer, made it his duty to fight against the oppression. His ideas and methods, often violent, became the grounding principles of urban guerilla warfare and rendered Marighella into Brazil’s folk hero as well as an inspiration to revolutionaries everywhere. The film follows the last years of Marighella’s life starting with his first arrest during the Dictatorship, throughout the foundation of his guerilla movement Ação Libertadora Nacional and its various acts of insurgency, up to his death at the hands of the police. It also shows Marighella as a leader, to the group of young revolutionaries around him, and a father to his teenage son, whom he has to send away to keep him from harm’s way.

WHO MADE IT: Wagner Moura is a Brazilian actor, who is best known for playing Captain Nascimento in José Padilha’s blockbuster Elite Squad, as well as Pablo Escobar in “Narcos.” He made his directorial debut with “Marighella”: a passion project that had been in the works for half a decade. Both Marighella and Moura share the hometown of Salvador in Bahia, and Moura had admitted that he’d had a fascination with Marighella since childhood, because the reason for the folk hero’s struggle, rampant inequality, had always surrounded him.

The film is based on Marighella’s biography by the journalist and writer Mário Magalhães. The cinematographer Adrian Teijido brought his capacity for capturing the contrasts between grittiness and hope that had marked his work on “Narcos”. Meanwhile, director Fernando Meirelles, known for “City of God”, “Blindness”, “Two Popes” and “The Constant Gardener” is an associate producer, alongside others.

Playing Marighella is Seu Jorge, the legendary musician from the favelas, as well as actor, who is best known for his work in “City of God” and “The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou”, and had previously worked with Moura in “Elite Squad 2”. Bruno Gagliasso plays the police chief Lúcio, who is sadistically bent on catching Marighella, and the award-winning Luiz Carlos Vasconcelos appears as Branco, Marighella’s trusty comrade through the thick and thin. The supporting cast that forms Marighella’s family and a group of guerillas is a beautiful display of diversity, both in skin color and character. Each of them portrays a whole world within appearances that are invariably cut short by the persecution.

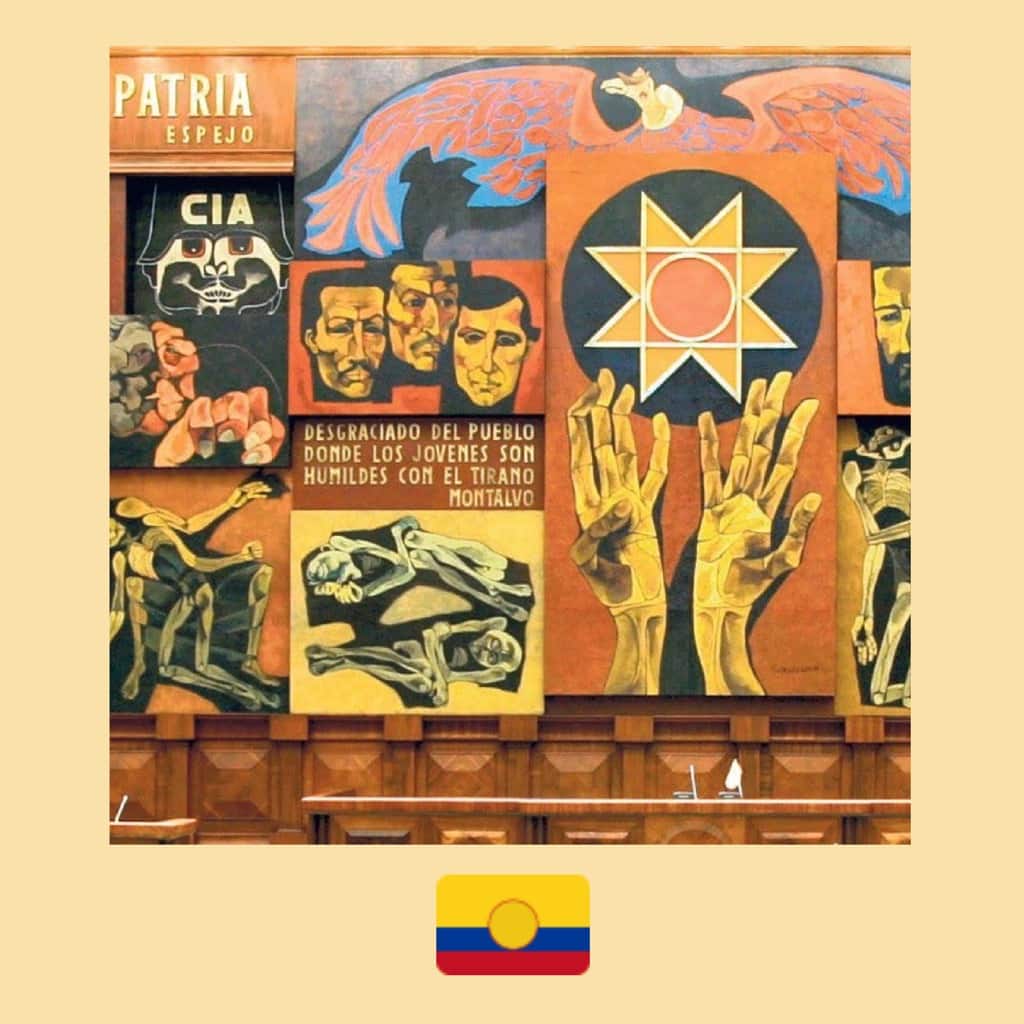

WHY DO WE CARE: As an uprising is overtaking the United States and spreading across the planet in the aftermath of the murder of George Floyd by the Minneapolis police, the discussion about the place of violence in protests has been driven to the forefront. Marighella offers a perfect encapsulation of what makes a revolutionary take up arms and fight. The film is in no way a substitute for Marighella’s much revered “Minimanual of the Urban Guerrilla”, the book that he authored shortly before he died as a metropolitan extension to Che Guevara’s ideology of warfare, and that became the grounding principle for the following generations of inner-city freedom fighters. And still, “Marighella” manages to explain why the protagonist saw no alternative to starting a violent insurgence and resort to such measures as the kidnapping of the US ambassador. Throughout the film, we see him relentlessly targeted by the Dictatorship’s forces, as his comrades keep being killed off in the most gruesome ways. The CIA,—the backer of the coup d’etat, which installed the Dictatorship in the first place, and the enforcers of Cold War anti-communist action across the world—keep working to get rid of the elusive guerilla leader. Meanwhile, the society, isolated by the restrictive regime and scared into submission, continues being absent from the political dialogue. This makes Marighella commit acts that would attract attention, whether it’s criminal activity or overtaking the airwaves by force in an act of cunning and daring. Whoever says that disrupting an authoritarian regime or fascism can be accomplished non-violently, had never even started trying. And Moura does not try to dilute the sacrifice that goes into this vital work.

One interesting aspect of the film is that Marighella—who was light-skinned and biracial, of an Italian father and Afro-Brazilian mother— is played by a much darker-skinned actor. Moura had explained the choice as a need to emphasize the importance of race in the Brazilian context. It also seems likely that this is the case because Seu Jorge is such a good fit for the role. The reason for him getting the parts of someone who didn’t look exactly like him is the reverse side of big-name actors being cast in significant parts of minorities they don’t represent. However, it is also indicative of an attempt to reverse the trend, where lighter actors had been made to play darker individuals so that they would seem more appealing to the general audience. With Marighella, this “overcorrection”, as Brazilian history researcher Wendi Muse has pointed out, leads to the erasure of a considerable part of Marighella’s identity. While he could pass for white, he chose to forego living out his privilege in complacency and decided to take the revolutionary path instead. On the other hand, a dark-skinned Marighella, while not historically correct, allows for a more prominent centering of a black person as a revolutionary fighting the forces of imperialism,—something we don’t really get enough of but should, especially in the current events, and especially within the Brazilian context, where racial disparity remains one of the biggest problems, and where, just like in the US, black children and adults alike are murdered extra-judicially by the police all the time. In fact, at the film’s premiere in Berlin, Mora highlighted the black struggle in contemporary Brazil by honoring the memory of slain queer black politician Marielle Franco and inviting her peer, queer left congressman Jean Wyllys, who had to resign because of death threats. Colorism issues aside, it’s a landmine to exist in the Brazilian landscape within any black body, and there’s no way to dismantle the landmine without learning from Marighella himself.

WHY YOU NEED TO WATCH: “Marighella” is immensely watchable. Despite the complex subject of the resistance to Brazil’s military Dictatorship and the protagonist’s personality, the film manages to put Marighella’s struggle into a concise underdog plot that keeps the viewer at the edge of the seat and holds the tension very evenly throughout the narrative. Beginning with a train robbery, which gives the story a folksy, exciting feel, “Marighella” then develops into a taut journey of a man seeking to liberate his country, keep his dignity and fulfill his promises all at the same time. As with many other portraits of fiercely determined revolutionaries, it becomes clear that being the guiding beacon demands immense sacrifices from the man. Seu Jorge inhabits the part of Marighella splendidly, the turmoil behind the steely, resolute facade palpable, and the gentleness that seeps through in the rare tender moments astounding.

The narrative is non-linear, and it makes omissions because detailing the whole spectrum of Marighella’s growth across the years, including his time spent in Cuba and China, where he sought to learn from the Mao and Castro’s successful revolutions, would take way longer than the 155 minutes. None the less, it offers a larger than life, intricate and mesmerizing portrait of the remarkable man.

Just like the violence on behalf of the uprising in the US protests—or, say, the bombardment of the US embassy in Athens with Molotov cocktails—the film’s frank portrayal of the brutal struggle of the revolutionaries has been rebuked by many. As if it exists in a vacuum, not in reaction to the immeasurable violence perpetrated by the Military Dictatorship, the police, or the imperialist and fascist forces.

The most prominent hater of the film is Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro, who often likes to evoke the Military Dictatorship with nostalgia, and call it “glorious”: he accused Moura of inciting violence by making the film. “Marighella’s” theatre release in Brazil was canceled, and the film experienced an onslaught of online attacks from the far right, who dropped the film’s IMDB rating to a low, despite resistance from the country’s left. Meanwhile, some American liberal reviewers found the film to glorify violence excessively.

And this is what makes “Marighella” so necessary to watch right now, and always. In a vast pool of milquetoast takes on equality and liberation, it does not pull any punches and delivers the revolutionary work in all its gore and glory, centered around one man, but populating a movement noble, fearless and inspiring. Making sure good wins over evil has never been a clean-cut ordeal, at least, not before the total corporate Disneyfication of art and culture. Watching “Marighella” is an act of political defiance both in Brazil and elsewhere, and learning about the person who sacrificed himself so that his homeland could be free,—not in 1969, but later, and not forever, but for a brief period,—is a necessity. You may not agree with his methods or consider them warranted, but anyone has to admit that daring to implement them takes singular bravery. When asked by a French journalist in the film, whether he is a Maoist, a Trotskyist or a Leninist, Marighella answered: “I’m Brazilian”. And so is the film about him, the first great work of resistance art of Bolsonro’s regime, a powerful debut of a blossoming Brazilian creator and thinker.

Marighella, 2019

Director: Wagner Moura

For more content like this sign up for our weekly newsletter

WATCH THE TRAILER