An intimate and haunting portrait of six teenagers in rural Transnistria shows the splintered prospects and the many limitations of growing up in a melancholy landscape

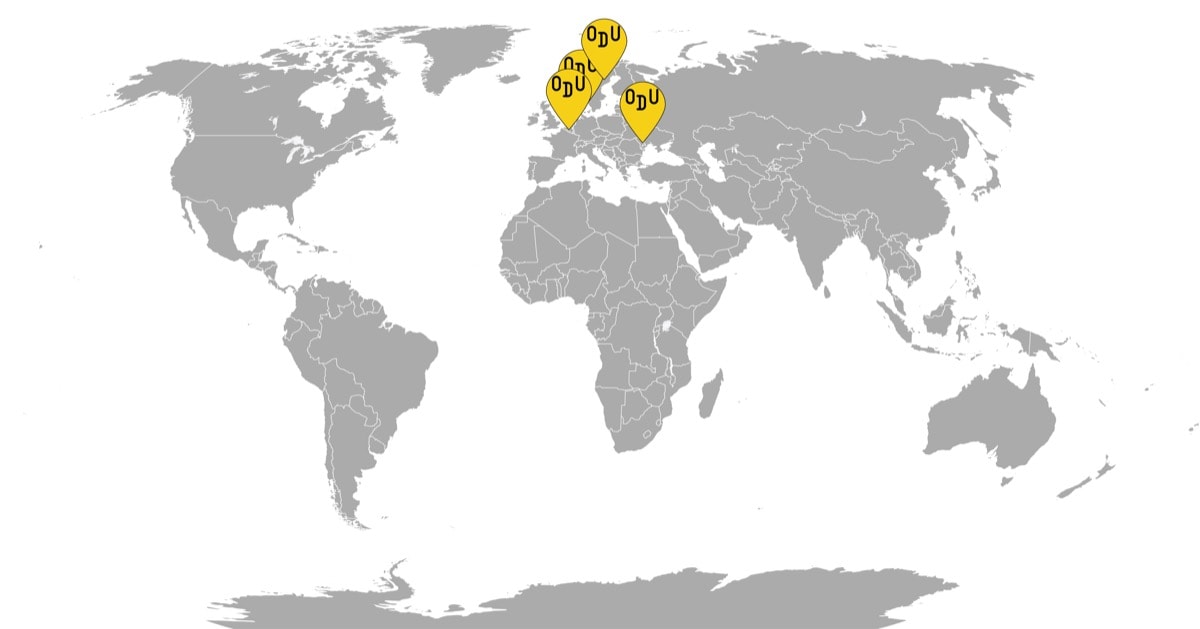

FROM TRANSNISTRIA, SWEDEN, DENMARK and BELGIUM

WHAT IT’S ABOUT: A bunch of young adults spends a languid summer in the town of Camenca, in rural Transnistria, the contested republic between Moldavia and Ukraine, which seems to be frozen in time. Tanya, the only girl in the group, wants to be one of the guys, while casually evaluating each of her friends as a prospective mate, a reckless force that only a 16-year-old girl may inhabit. First, she is with Dima, then with Sasha, all exhausted by the sun and willing. Will Denis or Burulya be next? But the quieter, yet arresting presence is Tolya, a boy with an invisible disability, who brings in the subdued wisdom and grounds the kids in the socio-economic constraints of the breakaway state. As winter comes, and then spring, the group’s dynamics ebb, and flow, personal pains are revealed, and it becomes clear that chances in Camenca are not doled out equally, and only some friendships will survive a tumultuous youth.

WHO MADE IT: Anna Eborn is a Swedish filmmaker, who has been exploring the remote corners of her homeland, as well as the US and the post-Soviet space and closing in on original, yet faint voices. She first gained prominence filming Oglala Lakota Indians in South Dakota, then sought female perspectives of wisdom and experience across Europe, and finally decided to spend time with teenagers for “Transnistria,” which she, like her other projects, directed, wrote and edited. A creature of habit, Eborn worked with some of the people who had previously helped her make “Lida” about the last remaining Old-Swedish speaker in Ukraine: some producers, including David Herdies, who was also responsible for producing “Ouaga Girls“, as well as the cinematographer Virginie Surdej.

The documentary’s subjects, Tanya Lipovskaya, Tolya Bucatel, and others, are all current or former residents of Camenca in Transnistria, the former part of Moldovia which broke away after the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

WHY DO WE CARE: “Transnistria” might not be dealing with subjects who have a load of experience to share, and their relationships could appear to be superficial. However, it’s as if a layer of internalized bias has been peeled off, which allows to see the interhuman connection for what it is, without diverting attention to the unnecessary. And then, most interestingly, the viewer gets to experience how free kids grow into complacency.

The film begins as an exploration of gender dynamics in a mostly male group of friends. In the summer heat and in the proximity of a muddy river, the half-naked, heartachingly young bodies, and the blossoming sexualities within make the atmosphere of the film loaded, like the air before a thunderstorm. Tanya has a boyfriend in the big city, and yet she longs to get a bite out of the boys, trying and discarding them by one, leaving them out to fight out the grievances. The one she doesn’t put into the rotation is Tolya, who both respectfully pines for Tanya but also sees her not as a conquest but as an equal, for which she seems grateful. Meanwhile, a rumor about two of the boys being gay is started, and even though we don’t know if it’s empty or not, the fragility of the ecosystem is further disturbed. What seemed like a rather peaceful mini-society, where the queen bee Tanya reigns, starts disintegrating: the girl’s earnest manipulations are rebuked, and the boys assume the positions to fight for dominance. The narrative becomes a seance of watching the patriarchy emerge seemingly out of nowhere, along with the rigid notions of what masculinity, femininity, and relationships must be. The kids are young, free, and don’t yet owe much to the world, and yet the restrictive carapace starts forming around them as if there was no other way to survive in the landscape than by assuming a position of complicity to the power structures.

WHY YOU NEED TO WATCH: “Transnistria” is a delightfully tender yet quite ruthless depiction of what life is like for a kid in the middle of nowhere. Camenca is bleak and almost has no distinguishing characteristics, but it largely informs Tanya and the gang’s prospects. And not merely due to the status of Transnistria on the international scene: Camenca is indistinguishable from millions of 10K population towns the world over, where the latest fashions have reached via technology, yet the opportunities remain hidden from view. Tanya appears to be the most privileged in the bunch,—it’s not disclosed how exactly although she seems to have a rich boyfriend at one point—but she eventually gets to travel abroad, lives in the big city, and returns in nice clothes. However, it doesn’t mean that her existence is faultless: in a tender interaction with her younger brother Vanya, it is revealed that Tanya is cutting herself. “I don’t understand you,” he says of the scars on her wrists. “Why did you do it to yourself? You should have asked me. I could have cut them. Then you wouldn’t be so sad.” Perhaps the most profound take on the mechanics of self-harm and depression from a runt who can’t be older than 11.

Vanya is on the cusp of leaving for military school, the only surefire form of social advancement in the widely unrecognized territory. Some of Tanya’s older friends go there, too. Meanwhile, for Tolya, it’s not an option: his disability disqualifies him from the military as well as a bunch of labor options, and the pension he is entitled too involves painful, dangerous evaluation process in the grasp of carcerative psychiatry. The viewer doesn’t want to suspend hope that things may turn out well for him, too. However, the way the other boys treat him differently starts seeping in, as it becomes clear that just like Tanya’s privilege, his diversity, neuro, and otherwise, is not welcome in the state of molting to fit the surroundings.

As the narrative wraps up, the film takes on a different dimension, when from a participant, Tanya becomes a documentarist. Tolya, from being just one of the few, emerges as the real moral center of the story: like Simon in “Lord of the Flies,” stuck between the brutal savagery of the boys and Tanya’s advancements into the civilization of capitalism. Tanya and the boys will grow, live, and maybe even thrive, leaving behind the shells of their previous selves. But it’s Tolya’s magnetism, his agelessness, his ability, despite the obstacles, to observe everything around him wisely, and his unrefined, odd brilliance that’s palpable through the screen. And it’s those things that render the boy, without a future but with a truth, a prophet-like figure, a single crystal-clear voice over the wasteland, unobstructed by the speech impediment. And this is where Anna Eborn lucked out in making “Trasnistra” most: she caught the very moment in Tanya’s life, where she went from just being a girl looking for warmth to an attentive, nurturing woman, who can see something special and absolutely heartbreaking in her friend, one she cherished and sheltered throughout. And the film ends with a powerful moment when she lets him step forward for his close-up, while there is still a chance.

An inimitable, subdued, and psychologically astute portrait of youth through the Surdej’s pastel-hued lens, “Trasnistra” manages to convey a lot with characters who don’t do or say much. A perfectly framed snapshot of a summer when promises still matter and the winter that comes after, it is timeless, able to evoke nostalgia while being contemporary and to stir a longing that nothing can quite quell. “Transnistra” is a well-made proof that seasons and times change, but the only thing that remains constant is the perpetuity of youth.

Transnistra, 2019

Director: Anna Eborn

For more content like this sign up for our weekly newsletter

WATCH THE TRAILER